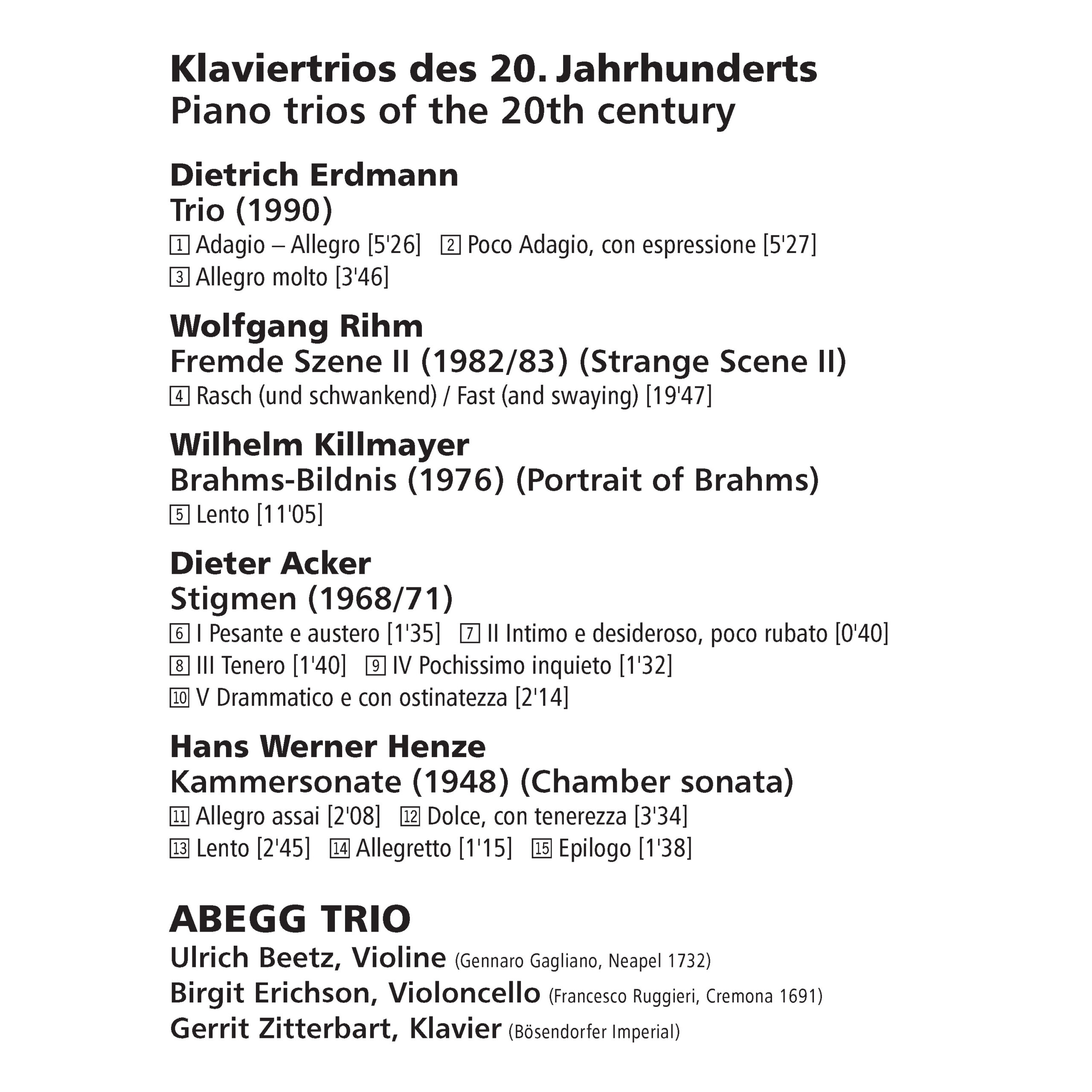

092 CD / Klaviertrios des 20. Jahrhunderts

Description

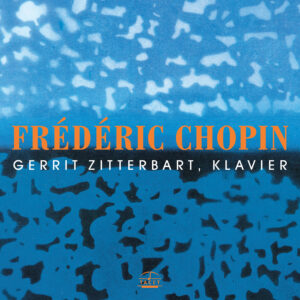

"...On their beloved subject of rarity and novelty, Ulrich Beetz (violin), Birgit Erichson (cello) and Gerrit Zitterbart (piano) have selected only those trios to which they can commit themselves, and the hairs of their bows, whole-heartedly (and with passion) – for music full of power, life, sound and colour." (Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung)

3 reviews for 092 CD / Klaviertrios des 20. Jahrhunderts

You must be logged in to post a review.

Bankok Post realtime –

This programme should more properly be called "German Piano Trios of the 20th Century" . If you are looking for the Abegg Trio′s interpretation of, say, Ravel′s great work in the genre you′ll have to look elsewhere in the Tacet catalogue. But the fact that all five of these pieces come from a single country (and that all but one of them were written during the second half of the century) takes no toll at all on the creative diversity of the music heard here.

In general, these pieces are more modest and accessible than some listeners might expect from Germanic music of the previous century. Unlike Schoenberg or Stockhausen, these composers are less interested in conceiving a new kind of music for the future than in contemplating or conversing with, and sometimes subverting, their country′s musical past.

Wolfgang Rihm′s Schumann-permeated Fremde Szene II, was composed in 1982/3 as part of a sequence of pieces described in a note by the composer as "experiments for piano trio, but also essays on the piano trio as such, this group of instrumentalists which is dominated by a piece of furniture which does not exist any more but still stands around."

In what follows he seems to be saying that evoking the past does not necessarily entail nostalgia for it, but I think that, as is so often the case when approaching a piece of tough contemporary music for the first time, it is better to simply listen and keep the composer′s explanations at a distance.

You don′t need him to tell you that the strange scenes he is conjuring up here have their dark side. The passionate, Schumann-style lyricism he mimics so expertly as the piece opens - music in the hard-breathing manner of the opening of the First Violin Sonata is subjected to Modernist cutting and scrambling - is drawn into a spinning sonic kaleidoscope of Romantic and Modernist gestures.

It sounds like an idea that is unlikely to sustain a 20-minute work, but Rihm uses it to propel music that hurtles along like an amusement park ride, and manages to keep the Schumann spirit intact throughout. The conclusion, where the strings sing their hearts out over a craggy piano accompaniment, then fall silent as the piano, stuck on a single, quiet chord, flickers away into silence, is tantalising, and the performance by the Abegg Trio is a knockout.

Wilhelm Killmayer′s Brahms portrait is less interested in doing violence to its subject′s music than in evoking its uniquely affecting ability to communicate the sadness that filled so much of his life. Killmayer′s music has not been widely available on recordings outside of Germany, but an EMI release of three cycles of Hoelderlin Lieder sung by Christoph Pregardien released during the early 1990s reveals a composer of great eloquence and depth.

The Brahms Bildnis is similarly direct - Killmayer remarks in a brief note that "interesting methods, so to speak" have lost their attraction for him.

The opening and closing passages of his portrait, long, melancholy-saturated singing lines for the strings, do not imitate the Brahms style, but have the same emotional tinge. Once the piano enters, its part becoming increasingly emphatic and mechanical, the music accumulates energy but, especially after about 6:50, the link with Brahms′s music (if not his personal life) seems to be lost until the mournful spirit of the opening returns to conclude the piece.

Hans-Werner Henze′s youthful Kammersonate, composed in 1948 during his student days, will refresh the ears of listeners who sometimes find themselves giving way under the thickness and weight of his more recent scores. The fast movements, like the opening Allegro assai, have a rhythmic energy and spiky harmonic language that suggests a Bartok influence, an impression that is reinforced by the hazy, dreamy sound of the Dolce, con tenerezzo second movement, which has a lot in common with the central movement of the Hungarian composer′s First Violin Sonata. But Henze′s own voice, the one that would soon be heard in the early symphonies, is clear.

Brahms makes another appearance in connection with Dietrich Erdmann′s Trio. It was written in 1990 while the composer was staying in the Brahms house in Baden-Baden and, as in the Killmayer piece, there is a Brahmsian air about the lyrical string writing in the first two movements. The Poco adagio second movement, with it dark opening cello solo, is especially beautiful. But the Trio is by no means an exclusively sad or introspective piece. The Allegro music in the first movement, and the nimble finale are full of spirit, and as a whole this piece is perhaps the most enjoyable on the programme.

Dieter Acker′s Stigmen is made up of five very brief movements, all but one of them lasting less than two minutes. There are Webern-like touches: the conclusion of the 40-second-long second movement and the attenuated sound world of the Lento that follows sometimes borrow the language of his early miniatures, but the open drama of Acker′s outer movements is all his own.

The Abegg Trio′s performances of this difficult music are powerfully communicative, and the recorded sound, as always with this label, is as good as it gets.

Highly recommended.

Ung-aang Talay

WDR, Forum der Musik –

…Anyone who has followed the concerts of the Abegg Trio will hardly be surprised by this commitment to contemporary music. What may surprise the listener, however, is the naturalness – indeed, the confidence – with which Ulrich Beetz (violin), Birgit Erichson (cello), and Gerrit Zitterbart (piano) devote themselves to each of the compositions. The CD’s programme features piano trios spanning four decades, beginning with Hans Werner Henze’s early Kammersonate of 1948, followed by Dietrich Acker’s Stigmen, Wilhelm Killmayer’s Brahms-Bildnis from 1976, Wolfgang Rihm’s Fremde Szene II, and finally Dietrich Erdmann’s Trio from 1990. This is a more than demanding programme and, to borrow Rihm’s words, a “foreign scene” (Fremde Szene), for, as he remarked, “Almost every music one attends is a foreign scene.” Each of these chamber works presents its own challenges both to the performers and to their listeners, and the Abegg Trio may deservedly be credited with turning the act of listening in each case into an event, an adventure, indeed a spiritual gain. Of course, the listener must engage thoughtfully – but in the end, the tenor of this Intercord (now Tacet) release becomes quite clear: it proclaims the unity of diversity, which the Abegg Trio conveys with skill and intensity, imagination and eloquence alike. Over the course of its career, the ensemble has already presented many interesting, demanding, and distinguished recordings, but this one occupies a special place among them – a distinction to which the reviewer can only offer sincere congratulations.

Ekkehard Kroher

Das Orchester –

A double “X” adorns the CD cover in raised relief – a clear signal that the 20th century is the focus here. The Abegg (Piano) Trio has concentrated its selection of works on the years following 1945. Yet all the compositions presented turn their gaze back in a kind of concerted action – without anger at the past – and at least partially affirm their connection to tradition.

In the Trio by Dietrich Erdmann – the eldest of the composers, born in 1917, though his work here dates back only four years – this becomes evident, for instance, in the solo string passages that open the first two movements: long, sweeping melodic arches, whose con espressivo marking in the Poco adagio the Abeggs realize with sensuous vibrato. In his Fremde Szene II (just over ten years old), Wolfgang Rihm deals more ironically with the “heritage” of the 19th century—perhaps precisely because he most overtly quotes the idiom of Robert Schumann (from whom, incidentally, the ensemble derived its name): here, elegant piano arpeggios; there, dramatically insistent chordal repetitions. Rihm humorously describes the piano trio as a “furniture-heavy ensemble that no longer exists, but still stands around.” “In abandoned rooms,” he says, “forbidden things can happen.” If one modifies “forbidden” to “unexpected,” one soon becomes familiar with Rihm’s musical language and its flashes of surprise—even though the pizzicato ending, punctuated by long pauses, startles once again. The Munich-based Wilhelm Killmayer, who after freeing himself from the formative influence of Carl Orff advanced toward a free tonality repeatedly infused with melody, offers in Brahms-Bildnis yet another sonic portrait of a composer—this time after Schumann in Endenich—focusing less on the heroic than on the chaotic aspect. When the piano suddenly bursts into a hammering treble passage, one is immediately reminded of the bizarre flageolet “E” in Smetana’s From My Life.

Two youthful works are encountered in Dieter Acker’s Stigmen and Hans Werner Henze’s Kammersonate. Acker’s lyricism, loosened by an uneven 7/8 rhythm, and Henze’s almost sweet confession to “full, wild sonority” in his Dolce movement, are further examples of the search for individuality without burning bridges to the past.

The Abegg Trio (which has now existed for nearly twenty years) transforms this search for traces into a sensuous listening experience. The ensemble’s name does not prescribe an absolutist program, but the classical-romantic repertoire (with its special reference figure Robert Schumann) remains an essential part of its activities. Thus, the committed program of this Intercord CD impresses as much as the rhythmically assured, sonically intense playing—which, on the other hand, does not soften the percussive episodes found in several pieces.

The booklet texts (biographies and work commentaries) are in part written by the composers themselves—concise and clear. An edition, therefore, not only for insiders, but also for newcomers.

Matthias Norquet