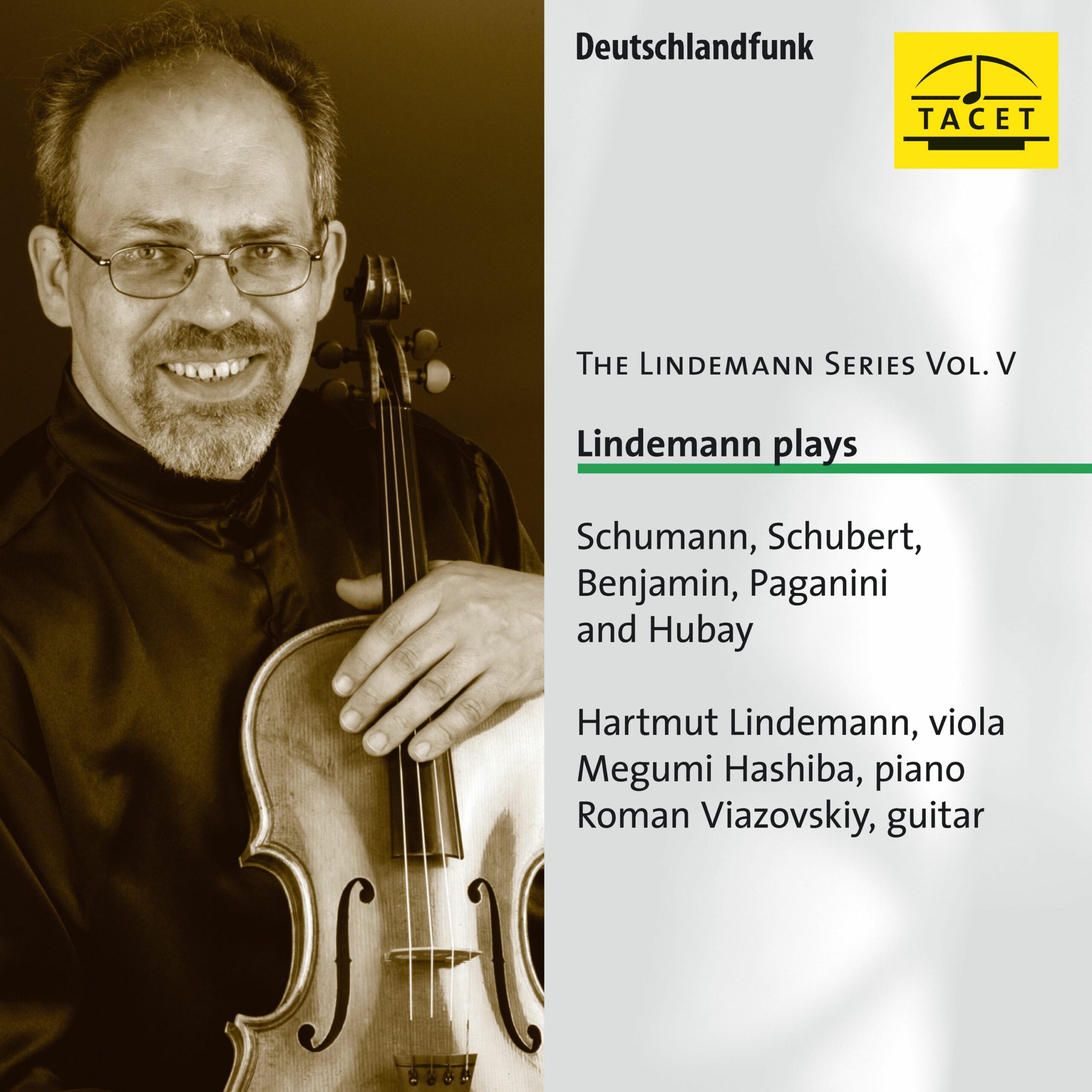

143 CD / Lindemann plays

Description

Hartmut Lindemann very rarely records a CD. This new one is only his fifth in fifteen years, anxiously awaited by his fans. The meticulous care he devotes to the production is all the greater. He structures his programmes as recitals in the old-fashioned sense, varied collections of witty, sensitive and virtuoso pieces; so it is no surprise that when he is asked about his artistic roots he only mentions a few role models from the early twentieth century. He plays the Arpeggione Sonata with guitar accompaniment instead of piano. This is not surprising, as the work was not composed for the viola, but for the arpeggione with piano. And his rendering of Schumann’s D Minor Sonata is most unusual when played on a viola. This recording must surely overshadow many a violin version. The recital is rounded off by a little recording of Hubay’s Zephyr, written in 1982.

6 reviews for 143 CD / Lindemann plays

You must be logged in to post a review.

Pforzheimer Zeitung –

Violist Hartmut Lindemann has already released a series of appealing CDs with TACET. (…) Lindemann is both a technically assured violist and an intelligent musical interpreter who relies fully on the rich tonal palette of his instrument. He is supported here by pianist Megumi Hashiba and, in the Schubert, by guitarist Roman Viazovski. An equally pleasing recording in terms of sound as well.

tw

The Strad –

Hartmut Lindemann is a unique player, who has made a study of the technical and expressive vocabulary of the old masters (such as Heifetz, Elman, Menuhin and Primrose) and upon that basis developed an unmistakable style of his own. No one today - and I mean this literally - plays quite the way he does. Schumann′s Violin Sonata sounds in Lindemann′s own arrangement almost better than the original, which keeps the violin in its less sonorous register too much of the time. In Lindemann′s virtuoso rendition one never misses the E string and, with bass notes added to some chords, the solo part acquires an impressive fullness.

Conversely, the transcription for guitar (by Konrad Ragossnig) makes the piano part of Schubert′s Arpeggione Sonata more fragile, but there are precedents for it, and the effect agreeably recalls the atmosphere of a Schubertiade. In Arthur Benjamins′s Viola Sonata, Lindemann unsurprisingly adopts some textual changes hailing back to the piece′s dedicatee, William Primrose. Paganini′s Caprice no. 9 (with piano accompaniment by Sydney Shimmin) and Hubay′s Der Zefir round off a spectacular recital that - in wonderfully warm sound - features playing one usually associates with the noise of shellac records.

Carlos María Solare

Audiophile Audition –

Hartmut Lindemann provides the usually scanty viola repertory some outstanding transcriptions, notably his musically gratifying transposition of the D Minor Sonata by Schumann, which Lindemann first presented in 2000 with pianist Hashiba. The aim here (2006) was to complement the viola versions of the Brahms clarinet sonatas with a major work by Schumann, so often the major influence on Brahms himself. Utilizing a "tenor viola" enhances the mid-range radiance of the instrumental colors, with no loss of the vibrancy and idiomatic melodiousness of the original. Certain other adjustments ensue, as Lindemann uses the high G and C strings to effect a "sul ponticello" directive by the composer. Hashiba’s Steinway D elicits its own autumnal colors, often of a virtuosic character. The octave leaps in the last movement quite tax Lindemann’s mettle, but he carries off the appearance of easy grace with admirable execution.

Lindemann performs Schubert’s uncanny Arpeggione Sonata with guitar accompaniment, a combinaton that strikingly approximates what the original instrument may have done for itself. Lindemann can deliver a "cello" tone with ease, lush and pliant at once. In his accompanying notes, Lindemann writes of searching for the "smile behind the tears" in Schubert. The fluency of the lyrical impulse, Lindemann’s high-bridged cantabile, compels our affection, as well as comparisons with Feuermann’s and Cassado’s cellos. If this were intended to be a "salon" performance, the scale of sound transcends that limit and ascends to rarer atmospheres. Lovely guitar effects in movements two and three, a real serenade of Iberian beauty by way of Vienna.

Arthur Benjamin’s Viola Sonata was written for William Primrose, who immediately praised its virtuosic qualities. The hands ply the entire fingerboard, creating effects that can be throaty and gruff to high-pitched, pointillist moments not far from Webern. In its lyrical episodes, a sweet melancholy pervades the piece, and we can easily place Lindemann’s inscription next to that of Primrose, if we had it. Originally entitled "Elegy, Waltz, and Toccata," the three movements furnish the solo with contrasting, mercurial elements for bravura display. The keyboard part, especially in the waltz section, proves audacious, while the viola effects some buzzing, improvised character alternating with martial impulses. The Toccata whirls, certainly, but it no less projects a manic, surreal drive, the registrations of the figures shifting virtually at every bar. The spirit of Hindemith seems nigh as the academic and the virtuosic compete for musical space.

The two short pieces, Paganini’s Ninth Caprice "La Chasse," and Hubay’s "Zehpyr," each ask for double-notes and swift alternation of bowed and plucked notes. The use of upbows in the Paganini creates some thrilling moments in the articulation of the staccati flute effects. The Zephyr derives from a 1982 Intercord LP, and it reveals more of the fire demon in Lindemann, who wanted broken triads to dazzle our ears. The middle enjoys a sincerity of expression, despite Lindemann’s later reservations about the reading.

Gary Lemco

Partituren –

That a label named “Tacet” (he is silent) is already releasing the fifth installment in a series of viola recordings almost sounds like a violist’s joke. But Hartmut Lindemann is no joke; he is a unique player who has developed an unmistakable style. No one today— and this is meant positively—plays quite like him. Schumann’s D minor Sonata, arranged for viola, almost sounds better than in the original for violin, and one never notices the added technical difficulties in Lindemann’s playing. Schubert with guitar accompaniment may sound somewhat Biedermeier, but it is entirely stylistically faithful. Benjamin’s Sonata, Paganini’s Caprice No. 9, and Hubay’s Zephir round off an outstanding recital.

CMS

Pizzicato –

That a virtuoso like Hartmut Lindemann is tempted to rework pieces originally written for violin into viola works is entirely understandable given his technical level. On this CD, only one original viola work is included—the Viola Sonata by Arthur Benjamin. All the other pieces have been arranged for viola, with Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata even adapted for viola and guitar. The result is sonically intriguing in these exciting and genuine interpretations, not to mention the sheer pleasure of listening to Lindemann’s expressive playing, in which he effortlessly and without any showmanship takes the viola into its highest registers, where it almost sounds like a violin. Pianist Megumi Hashiba and guitarist Roman Viazovsky contribute atmospherically to the interpretations, making this a very special chamber music CD that comes highly recommended.

RéF

Klassik heute –

Höchstnote 10 für künstlerische Qualität und Klangqualität

As indispensable as it is in the quartet and orchestra, the viola (or Bratsche, derived from Viola da braccio) remains something of an exotic solo instrument. The Tacet label champions this “stepchild” of the string family with its series dedicated to violist Hartmut Lindemann. Unlike others who “step down” from the violin to the larger, lower-pitched viola, Lindemann began directly as a viola player and is therefore a true “noble violist.” He now teaches at the Musikhochschule Detmold/Münster and is regarded as one of the greats of his instrument.

Die fünfte Folge der Serie kann gleich mit zwei Repertoire-Highlights aufwarten. Die als Auftragswerk für den berühmten Bratscher William Primrose geschriebene Sonate von Arthur Benjamin zählt ohne Frage zu den dankbarsten Werken der Viola-Literatur. Der erste der drei Sätze „Elegy, Waltz and Toccata“ reflektiert die düstere Stimmung des Entstehungsjahrs 1942, der Walzer ist von dekadentem Charme und das Finale lässt an Brillanz nichts zu wünschen übrig.

The Arpeggione Sonata by Schubert, performed on the viola, has always convinced us the most—it best suits the range of the solo part and, with its “veiled” tone, conveys Schubert’s “smile through tears” like no other instrument. Lindemann plays this often-mistreated work with assured taste, consummate expression, and extraordinary flexibility in tone. Roman Viazovskiy provides the perfectly intimate framework with his sensitive guitar accompaniment (in Konrad Ragossnig’s arrangement).

A somewhat more unusual program item is Robert Schumann’s Violin Sonata in D minor, yet Lindemann’s reasons for adapting this magnificent work for viola, explained in the booklet, seem entirely plausible—and the resulting sound confirms him. The Japanese pianist Megumi Hashiba, a lecturer at the Cologne University of Music, is a congenial partner here, as she is in the Benjamin Sonata. As a kind of encore, there is also Paganini’s Ninth Caprice and a piece by Jenő Hubay—the latter from a twenty-five-year-old analog recording.

Otherwise, the recordings are of recent date and of the highest quality. Andreas Spreer has captured the sound of the instruments with every nuance in utmost clarity and naturalness—completely without gimmicks. Only the booklet could use a bit more care: the composers’ birth and death dates are not provided, and Arthur Benjamin is described in the text as “living in England”—the composer, born in Australia in 1893 and who, among other things, taught piano to Benjamin Britten at the Royal College of Music, actually died in 1960.

Sixtus König