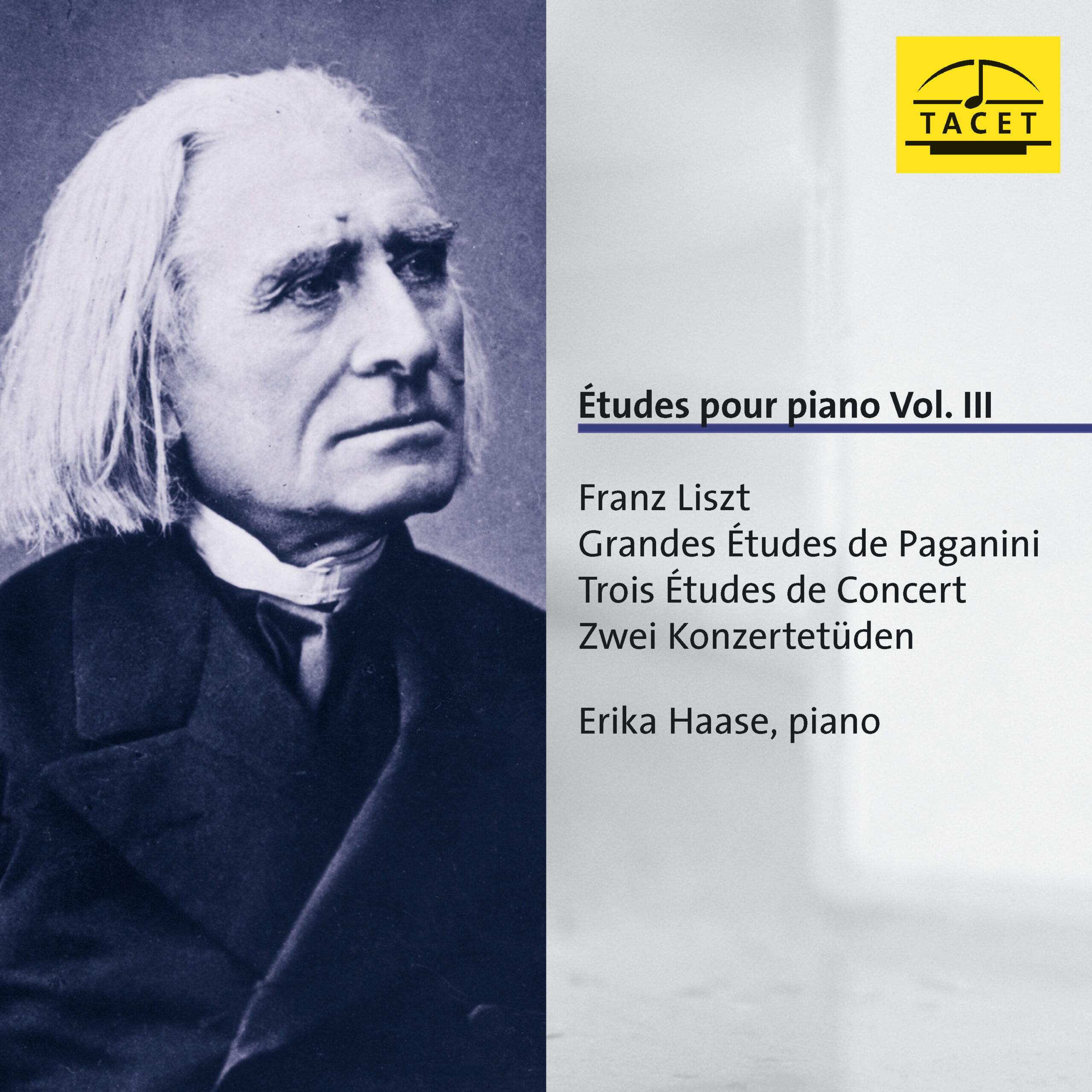

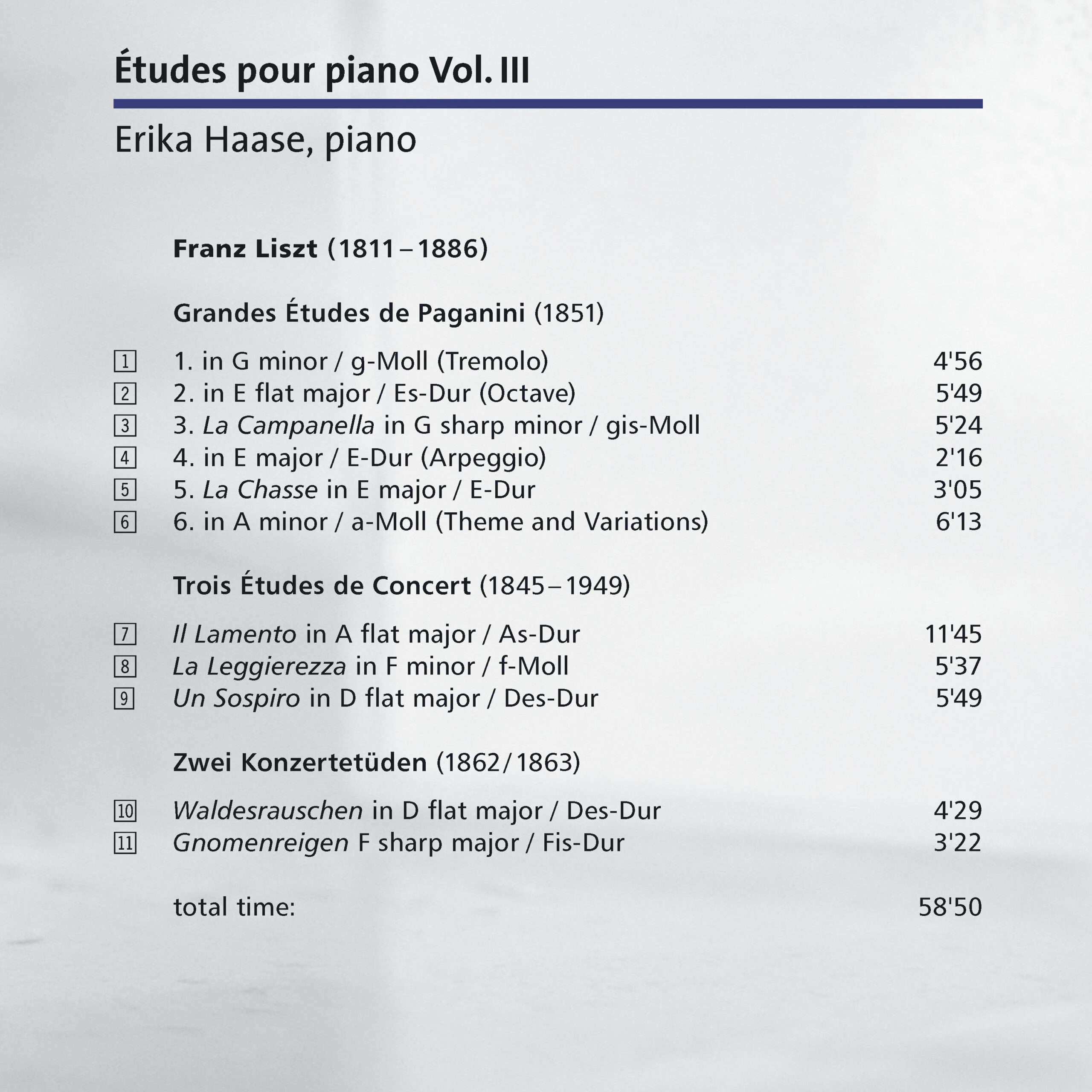

150 CD / Études pour piano Vol. III: Franz Liszt

Description

Erika Haase continues her ambitious project of recording the most significant etudes of piano literature. This time she has tackled the etudes by Franz Liszt. The daredevil difficulties for the pianist playing these works are legend. She masters them with bravura and enriches them with her own highly sensitive musical note.

6 reviews for 150 CD / Études pour piano Vol. III: Franz Liszt

You must be logged in to post a review.

DRS2 Studio Basel –

Liszt composed music that remained unplayable for many of his colleagues—simply because it was too difficult. And even today, in an era with György Ligeti’s almost inhumanly treacherous études, many still dare not attempt Liszt. After all, he doesn’t sound good when the audience can tell just how hard he is to play.

Bei der deutschen Pianistin Erika Haase merkt man das ganz und gar nicht. Die zweiundsiebzigjährige spielt mit Genuss Ligeti und ist jetzt an einer Gesamteinspielung von Liszts Klavieretüden.

Liszt war fasziniert vom Grenzgängerischen und so schrieb er viele Etüden, wo er eben diese Grenzen auslotet, z.B. große Etüden nach dem Vorbild seines Bruders auf der Geige: Niccolo Paganini.

„Grandes Etudes de Paganini“ nennt Liszt diesen Zyklus. Am berühmtesten wohl ist die Etüde „La Campanella“ und hier salutiert sich Liszt an der neuen Erfindung des modernen Klavierbaus damals: an der Repetitionsmechanik. Sie erlaubt schnelle Tonwiederholungen. Ja, und wenn diese verzwackte Musik so leicht daherkommt wie bei dieser Pianistin, ist es ein Vergnügen, zuzuhören.

RéF

arte-TV –

Liszt’s piano études are not for beginners. Anyone who wants to play the Transcendental Études, the Paganini Études, the Three Concert Études, or the Two Concert Études must be technically flawless. The composer was inspired to create his études in part by the violin virtuoso Paganini, who, in the 19th century, pushed the boundaries of his instrument like no other musician. By transcribing Paganini’s works, Liszt sought to achieve something comparable on the piano—both in terms of sound and technical mastery.

Liszts äußerst schwierige „Paganini-Etüden“ existieren in einer ersten Version von 1840, die einige wagemutige Pianisten noch heute spielen, obwohl gewisse Passagen auf einem modernen Klavier praktisch nicht mehr ausführbar sind. Erika Haase entschied sich für die endgültige Fassung von 1851, und zwar nicht aus Angst vor der Herausforderung, sondern weil die von Liszt revidierte Version ganz einfach die wirkungsvollere ist. Erika Haases Spiel ist ein Muster an Klarheit. Die Pianistin versucht nicht zu glänzen, indem sie die virtuosesten Stellen hervorhebt, sondern behandelt diese Passagen ganz einfach wie unberechenbare musikalische Regungen, die plötzlich auftauchen wie Gnome in einem verwunschenen Wald. Dieser Aspekt ist sicher wesentlich. Wie sonst könnte man die berüchtigte „Leggierezza“-Etüde spielen, deren Tontrauben prasseln wie Frühlingsregen auf einem Ziegeldach?

Die Anmut der deutschen Pianistin ist wirklich beeindruckend. Unter ihren Fingern wird Liszt wieder der Zauberer, der er zweifellos war. Die Klarheit ihres Spiels wurde bereits erwähnt, aber man könnte auch von klanglicher Raffinesse sprechen, jener anderen Qualität der Lisztschen Musik, die allzu oft vergessen wird.

Mathias Heizmann

Audiophile Audition –

The works shimmer in magisterial harmony and convey atmosphere to spare

Erika Haase (b. 1935) boasts a strong artistic pedagogy, having studied with Edward Steuermann and Conrad Hansen. A teacher at State School, Hanover Music and Arts, she is to piano instruction what Uta Hagen was to acting. Her powerful technique can be savored in these studies Liszt developed especially for his own prowess, as well as serving as homage to Nicolo Paganini, the greatest violinist of his time. The Six Paganini Etudes (1840; rev. 1851) rarely receive integral recordings, and it is a pleasure to hear Haase′s Steinway D (rec. 2006) in blazing, even mesmerizing Technicolor sound, courtesy of engineer Andreas Spreer.

Haase′s octaves are a lesson unto themselves; witness her E-flat Major Etude based on Paganini′s 17th Caprice. The first Etude in G Minor exploited a continuous trill that proves quite ferocious. Dazzling repeated notes constitute La Campanella in G Sharp Minor, with references to the triangle part in Paganini′s B Minor Violin Concerto. While I personally rank Nojima′s version as stupendous, Haase makes my skin quake just as well. The E Major imitates the violin′s arpeggio and bariolage techniques, which leads to some torturous fingering for a pianist, her two hands competing for room in a confined space. The E Major No. 5 "La Chasse" imitates a hunting horn and flute motif, with huge spans among the notes. Brilliant staccato work and slick runs from Haase.

The A Minor is the most familiar, having enjoyed treatment from Brahms, Rachmaninov, and Lutoslawski. A series of bravura variations, the piece tests metric precision, sustaining pedal, and digital dexterity, as well as degrees of dynamic subtlety. Haase manages a terrific tension in this etude, delivered in one fell swoop.

The three Concert Etudes (1845-1849) contain one rarity, the opening Il Lamento in A-flat Major, a tonepoem for keyboard that opens with an improvisation and proceeds to a Cantabile of grand rhetorical and sensual scope, really a sparkling, plastic nocturne from the religious and poetic harmonies of Liszt. The chromatic scales and parallel sixths of La Leggierezza - the F Minor study in touch and thematic transformation - proves mother′s milk to Haase′s florid technique, which can charm as well as dazzle. Un Sospiro (D-flat Major), with its crossed hands and liquidly erotic effects, makes a strong impression, especially in the virtuoso cadenzas.

Finally, two concert etudes that Liszt composed for an 1863 book of pedagogical exercises: Waldesrauschen and Gnomenreigen. The former has swirling patterns and makes the demands of a contrapuntal perpetuum mobile. Gnomenreigen is Liszt′s answer to Mendelssohn fairylands. Played with declamatory and bold panache by Haase, the works shimmer in magisterial harmony and convey atmosphere to spare.

Note that this all-Liszt recital constitutes the third of Haase′s editions devoted to etudes, the former volumes dedicated to Debussy, Stravinsky, Ligeti, Messaien, Bartok, and Scriabin."

Gary Lemco

Pizzicato –

Liszt at his most atmospheric

Unperturbed and tirelessly industrious, the now 71-year-old German pianist Erika Haase continues her work on Liszt’s études with a distinct sense of individuality.

In his études, too, Liszt primarily transformed intellectual impressions—inspired by his deep engagement with art and literature. It is here that the pianist finds her interpretive approach, for what matters to her, surely shaped by a wealth of life experience, is not dazzling virtuosity but rather the rich tapestry of moods within the music. Liszt, who demonstrated through his symphonic poems how essential Klangmalerei (tone painting) was to him, might have appreciated these thoughtful performances. After all, mere virtuosity was never his true aim—he did not want to be just an "entertainer."

This CD, like its two predecessors, occupies a unique and special place in the spectrum of Liszt interpretations.

RéF

KulturSPIEGEL –

Legions of pianists have wrestled with these finger-knotters; recordings are everywhere. But it’s worth lending an ear to Erika Haase, professor in Hanover: the “Dance of the Gnomes,” for example, has seldom been played with such structural clarity and at the same time such warmth – Liszt with a twist, you might say.

Johannes Saltzwedel

NDR Kultur, Neues vom Schallplattenmarkt –

Pianist Erika Haase has kept a low profile in recent years, but she gained particular renown for her concerts featuring Ligeti’s études—once considered unplayable—uncovering and articulating their profound musical substance. In her latest CD program, the pianist, born in 1935 in Darmstadt, presents piano études by Franz Liszt. Here, too, she impresses with a unique blend of virtuosic technique and the deepest musical insight. The pieces must never betray their technical challenges, and one can only marvel at the ease and romantic sweep with which Haase delivers Liszt’s études. This program of Liszt’s piano études, with its lightness and aura, fits wonderfully into the summer festival season, as it is infused with a magical musical spirit. In Erika Haase, we encounter a pianist who shares her joy of music with us, almost playfully poking fun at the grand spectacle that the 19th-century salon lions loved to make of these études.

Margarete Zander