152 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. V: Max Reger

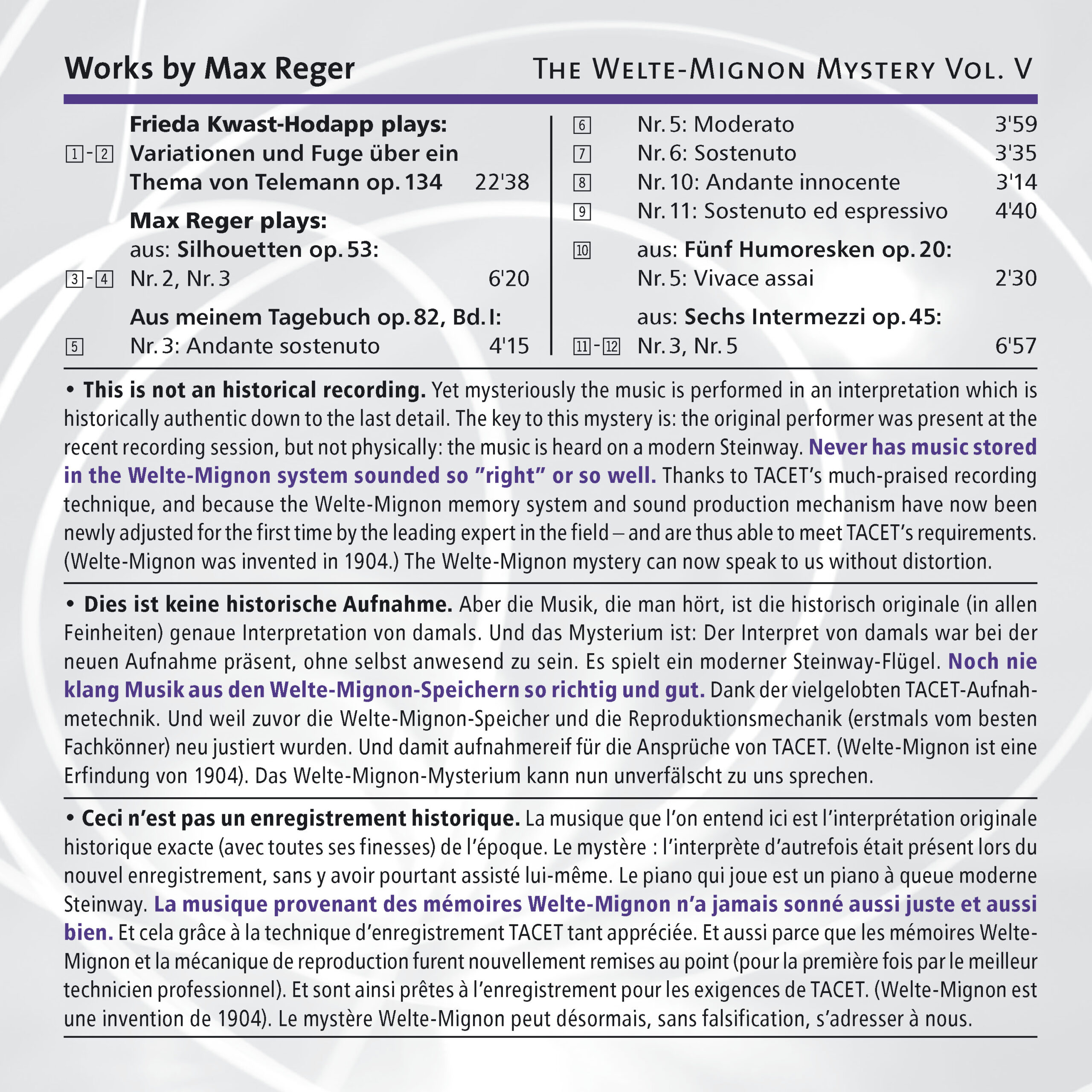

The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. V

Max Reger

and Frieda Kwast-Hodapp today playing their 1905/1920 interpretations. Selected works by Reger

EAN/barcode: 4009850015208

Description

This is not an historical recording. Yet mysteriously the music is performed in an interpretation which is historically authentic down to the last detail. The key to this mystery is: the original performer was present at the recent recording session, but not physically: the music is heard on a modern Steinway. Never has music stored in the Welte-Mignon system sounded so "right" or so well. Thanks to TACET′s much-praised recording technique, and because the Welte-Mignon memory system and sound production mechanism have now been newly adjusted for the first time by the leading expert in the field - and are thus able to meet TACET′s requirements. (Welte-Mignon was invented in 1904.) The Welte-Mignon mystery can now speak to us without distortion.

3 reviews for 152 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. V: Max Reger

You must be logged in to post a review.

Pianiste –

THE LESSONS OF THE PAST

The Magic of the Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… spielen ihre Werke.

Would you like to hear Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, and Reger playing their own works on a modern piano? And how about a "perfect" restoration of the interpretations by the early Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne, and Schnabel? The German label Tacet offers an anthology of rolls recorded by the Welte-Mignon system. The system is simple, but the process of reproduction is particularly complex! In fact, the pieces played by the composers themselves were digitized from the device invented in 1904 by the company Welte & Sons of Freiburg. The perforated rolls of the time captured the touch, pedal play, and the finest nuances. Today, all that is needed is to transfer these recordings onto a concert piano.

It is therefore a real shock to hear, in optimal listening comfort, Debussy’s Children's Corner and some Préludes, as well as Ravel’s Sonatine and Valses nobles et sentimentales, all played by the composers themselves. What lessons can we take away from this? First, the astonishing freedom with which these two geniuses approach their scores! It is also true that Ravel’s playing is not always flawless… But if we look beyond the purely technical aspect, we notice the extreme finesse and personalization of their touches. The dynamics are generally soft, with the fingers seeming to merely caress the keyboard. No brutality whatsoever. The clarity and gentleness are astounding. Other examples are equally striking, such as the two volumes dedicated to Brahms’ works interpreted by Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney, or Chopin’s Etudes played by Pachmann and Paderewski…

The virtuosity of these pianists is staggering, but even more surprising is the passion, the commitment, and sometimes even the coquettishness, the occasional unnecessary ornamentations that some perform almost as if they were tics. From all these master lessons, we learn that the strongest personalities only flourish after a visceral and profound understanding of the works. Schnabel in the waltzes of Josef Strauss and Josef Lanner (who would dare play this today?), Horowitz in 1926 in some Rachmaninoff Preludes, speak to us. Where does the charisma and charm of their interpretations come from? A mystery.

Every year, Tacet releases three or four new CDs from the Welte-Mignon archives. Worth collecting.

S. F.

_________________________________________________

Original Review in French language

LES LEÇONS DU PASSÉ

La magie des Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… jouent leurs œuvres.

Vous aimeriez entendre Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, Reger jouant sur un piano d’aujourd’hui leurs propres Oeuvres? Et que diriez-vous aussi d’une restitution « parfaite » des interprétations des premiers Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne et autres Schnabel? Le label allemand Tacet propose une anthologie des rouleaux gravés par le procédé Welte-Mignon. Le système est simple, mais le procédé de restitution particulièrement complexe! En effet, les pièces jouées par les compositeurs eux-mêmes ont été numérisées à partir de l’appareil inventé en 1904 par la firme Welte & Fils de Fribourg. Les rouleaux perforés de l’époque ont capté le toucher, le jeu des pédales et les nuances les plus fines. Il suffit aujour¬d’hui de transférer ces témoignages sur un piano de concert.

C’est donc un véritable choc que d’entendre dans un confort d’écoute optimal les Children’s Corner et quelques Préludes par Debussy, mais aussi la Sonatine, les Valses nobles et sentimentales de Ravel sous les doigts des compositeurs. Quelles leçons en retirons-nous? D’abord, l’étonnante liberté de ces deux génies vis-à-vis de leurs partitions! Il est vrai aussi que le jeu de Ravel n’est pas d’une justesse infaillible… Mais si l’on dépasse l’aspect purement technique, on s’aperçoit de l’extrême finesse et de la personnalisation des touchers. Les dynamiques sont généralement faibles, les doigts semblent effleurer le clavier. Sans aucune brutalité. La clarté et la douceur sont stupéfiantes. D’autres exemples sont frappants comme ces deux volumes consacrés à des œuvres de Brahms interprétées par Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney ou bien les Études de Chopin par Pachmann et Paderewski…

La virtuosité des pianistes est stupéfiante, mais on est plus surpris encore par la fougue, l’engagement, parfois même les coquetteries, les ornementations intempestives que certains provoquent comme des tics. De toutes ces leçons de maîtres, on retient que les personnalités les plus fortes ne s’épanouissent qu’après une compréhension viscérale et profonde des œuvres. Schnabel dans les Valses de Josef Strauss et de Josef Lanner (qui oserait jouer cela aujourd’hui ?), Horowitz en 1926 dans quelques Préludes de Rachmaninov nous interpellent. D’où proviennent le charisme et le charme insensés de leurs lectures? Mystère.

Chaque année, Tacet publie trois ou quatre nouveaux CD des archives Welte-Mignon. À thésauriser.

S. F.

Fono Forum –

Dead men playing

Since Telefunken released the first monaural 25-centimeter LPs with transfers from piano rolls in 1957, efforts to rediscover the treasure trove of nearly 20,000 paper sound carriers from nearly three decades have never ceased. These rolls preserve the performances of the most famous pianists of their time in a sound quality far surpassing the capabilities of contemporary shellac records. Now, TACET continues its series "The Welte-Mignon Mystery," which began in 2004, with volumes 4 and 5. When listening to Frieda Kwast-Hodapp performing the Telemann Variations on the new Reger CD, the illusion is already quite compelling—it feels as though a living, breathing person is sitting at the keys on the other end, not just a mechanical box. This even raises serious doubts about whether the widely held belief among experts and collectors—that piano rolls inherently have less documentary value—can still be upheld without reservation.

But these two new CDs are also—and above all—fascinating in terms of content. The Reger CD confirms that Frieda Kwast-Hodapp was rightfully celebrated as one of the most significant pianists of her time. Her 1920s recording is lively and generous; after some initial rubato flourishes, she powerfully navigates the étude-like early variations, sustains tension, and brings out the climactic finale with compelling intensity. The recording is complemented by ten pieces from Reger’s Humoresques, Op. 20, Intermezzi, Op. 45, "Silhouettes," Op. 53, and "From My Diary," Op. 82—works that Reger himself recorded as early as 1905. Some of these are old favorites, but hearing them all together now deepens admiration for Reger’s piano playing, which—much like Kwast-Hodapp’s—was always focused on the overall structure, subsuming every detail into the whole. The second "Mystery" release is even more of a sensation: It compiles 19 of the 24 Chopin Études (Op. 10 and Op. 25) from the Welte repertoire, performed by 15 different pianists. The list ranges from legends like Pachmann, Essipowa, Paderewski, and Sauer to Lhévinne, and even includes young prodigies of the time—Schnabel, Horowitz, Elly Ney, and Serkin—heard here as teenagers (though the birth years listed for Paderewski and Horowitz are incorrect). For the remaining five études, Peter Orth stepped in as the performer, leaving listeners to guess whether each étude comes from a piano roll or is played live—hence TACET’s playful title: "Dead or Alive."

It’s not too hard to tell—but not because of sound quality. The difference lies in pianistic style: Orth plays with noticeably straighter, more studious phrasing than the “dead men” (and women). At 23, Schnabel sounds surprisingly fidgety, far less “classical” than Horowitz, of all people. Serkin dazzles in the “Tempest” Étude, while Emil Sauer lives up to his reputation as a virtuoso elegance. Elly Ney’s C-sharp minor Étude is so drenched in rubato that barely a note lands where expected. And then there’s the real shock: In the famous E-major Étude, an obscure pianist from Freiburg effortlessly holds her own against the deified Paderewski—just one of many curiosities this CD offers. A feast for the ears, and not just for piano aficionados and historians!

Ingo Harden

Klassik heute –

Even today, they hold a magical fascination: the paper rolls created a century ago, which set the keys of a piano or grand piano in motion as if by ghostly hands. Using a complex mechanism, they were capable of reproducing the individual playing styles of pianists—with remarkable authenticity in terms of agogics and dynamics. The greatest pianists of their time, from Eugen d’Albert to Ignaz Paderewski, immortalized themselves on the Welte-Mignon piano, until it was displaced by records and radio in the early 1930s. Around 1960, these treasures were rediscovered, and efforts began to transfer the old recordings from piano rolls to vinyl. By that time, however, some of the original calibration instructions had been forgotten. As a result, while listeners could enjoy the stars of the past without the hiss and crackle of historical recordings, they had to contend with tempo issues and pitch fluctuations.

Now, a new era—a kind of third life—has begun for the Welte-Mignon recordings. Specialist Hans-W. Schmitz has achieved a precise calibration of the apparatus, reducing tempo deviations to a minimum. Meanwhile, producer Andreas Spreer’s keen ear, combined with state-of-the-art technology, ensures a pristine reproduction of the full sound spectrum of the modern Steinway D concert grand piano, to which the Welte-Mignon reproducing mechanism is connected.

Even though some questions about the "authenticity" of these recordings remain unanswered—such as the limited dynamic range, the fact that the original instrument and acoustics likely differed significantly from those of the reproduction and new recording, and the unknown alterations that may have occurred when transcribing the performance onto a punched paper roll—these recordings are unique documents that convey a highly significant impression of each artist’s playing. This is further confirmed by the surviving comments of the musicians themselves. Max Reger saw the "Mignon" as an "invention of inestimable value", which he gladly used to establish a tradition of reproducing his own works. Thus, we experience his series of smaller pieces as he recorded them on December 8, 1905, in Leipzig—with remarkable rhythmic freedom, poetic expression, and a "soulful" quality (as a contemporary concert review put it). The pianistically impressive recording of the great Telemann Variations comes from Frieda Kwast-Hodapp, to whom Reger had entrusted the world premiere of the work. She performs a slightly abridged version, authorized by the composer himself.

The carefully designed booklet provides fascinating insights—both in text and images—into the Welte-Mignon process and the present recording. A valuable addition for all piano enthusiasts and indispensable for Reger aficionados.

Sixtus König