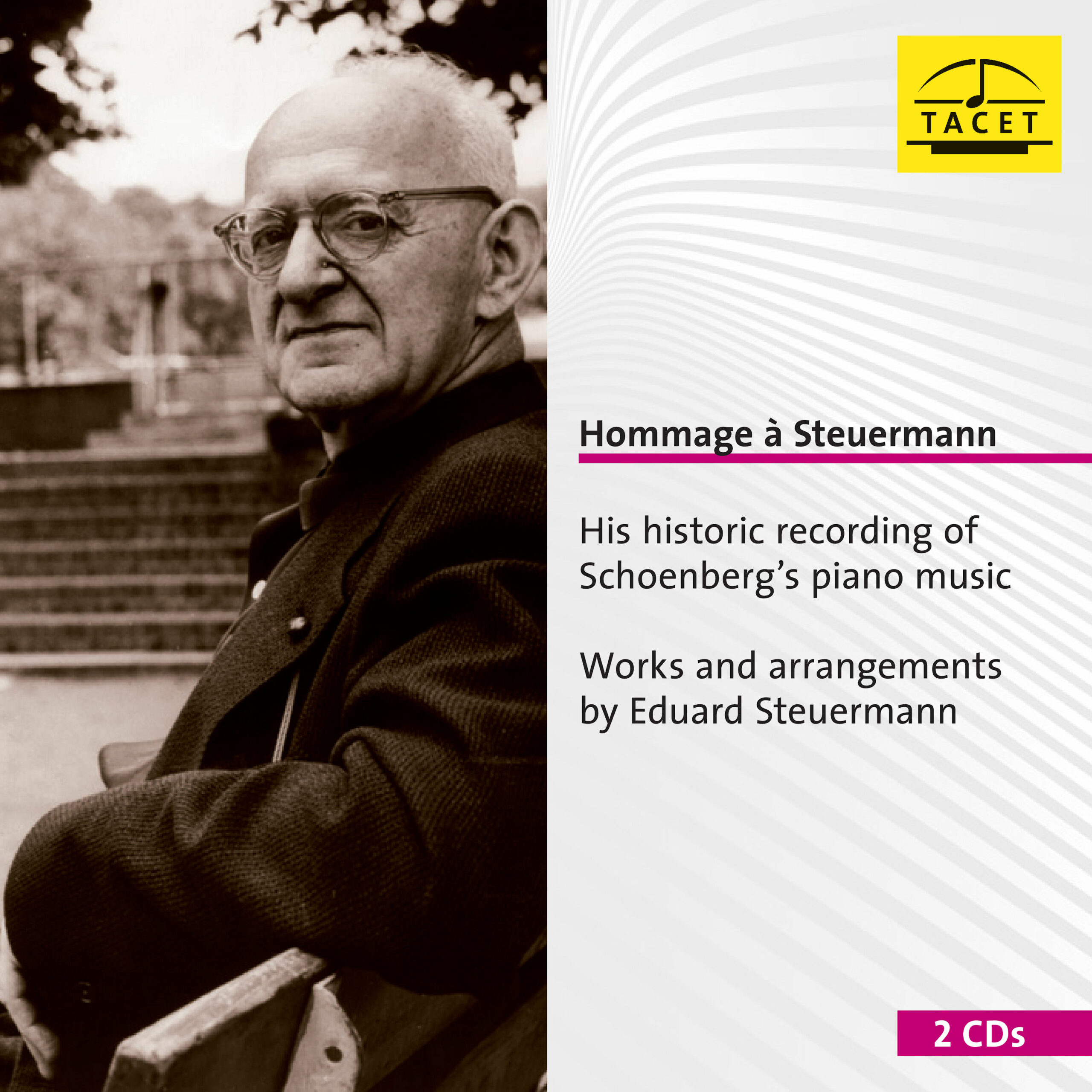

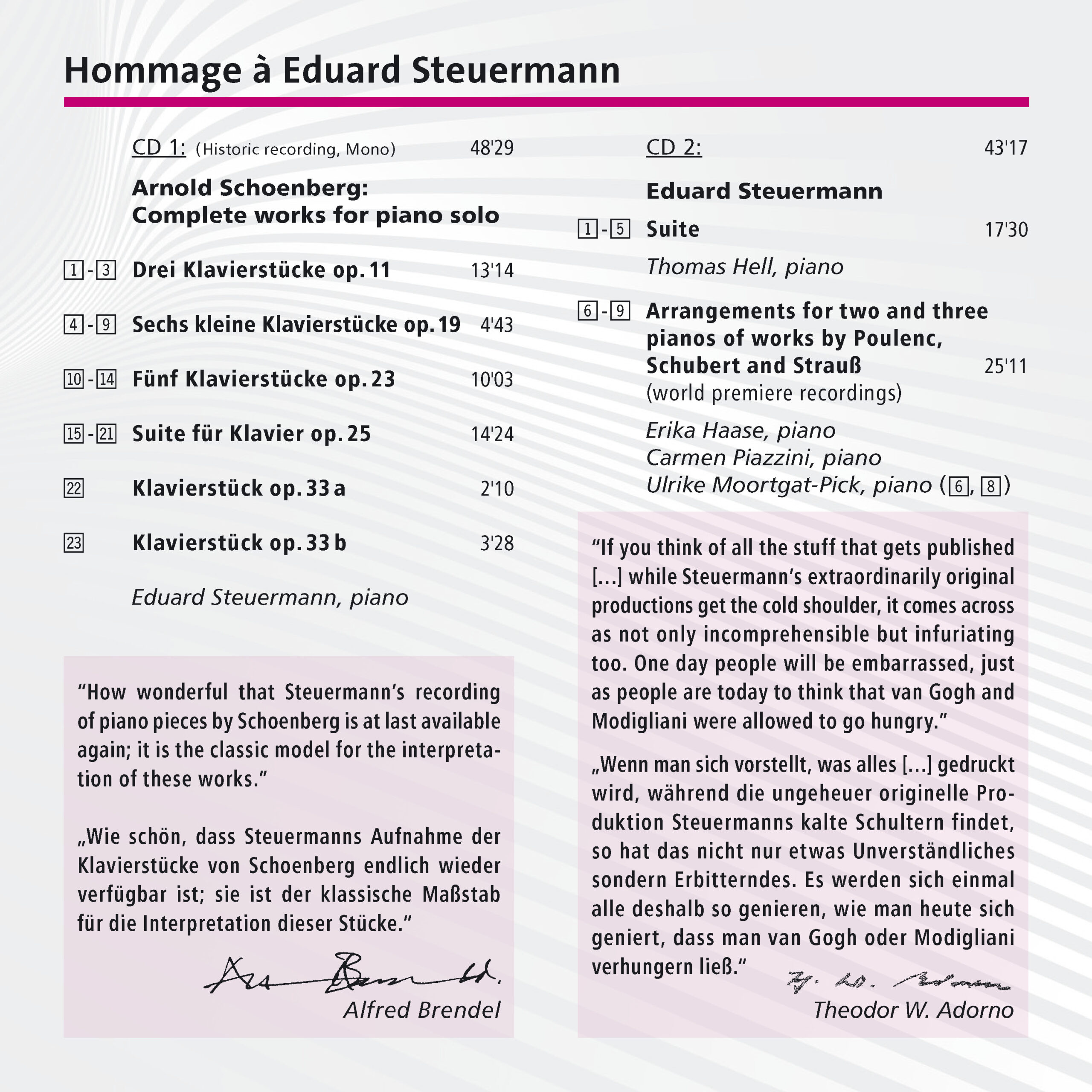

186 CD / Hommage à Steuermann

Description

Einen Sonderpreis erhält die diskographisch wohl bemerkenwerteste Veröffentlichung des letzten Jahres, die „Hommage à Steuermann“, also an Eduard Steuermann, den großen Pianisten, Weggefährten und Freund Arnold Schönbergs. Er spielte als erster dessen Gesamtwerk für Soloklavier ein, bei aller zwölftönigen Notenmathematik aufregend sinnlich und greifbar nahe. Lange Zeit galten diese Columbia-Records-Aufnahmen als „verschollen“, es gab sie nur auf alten Schellackplatten. Sie wurden nun sorgfältig restauriert. Die Edition bringt, als Bonus, auf einer zweiten CD Kompositionen von Steuermann selbst, seine Suite (ebenfalls sehr sinnliche Zwölftonmusik) und geistreiche Klavier-Paraphrasen, unter anderem der Johann Strauß’schen „Fledermaus“. (Thomas Rübenacker)

19 reviews for 186 CD / Hommage à Steuermann

You must be logged in to post a review.

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

Recommendations from our music critics

1957 entstanden, ist diese Schönberg-Einspielung durch seinen Lieblingspianisten noch immer mustergültig – lehrreiche Schule und Hörgenuss in einem.

Uwe Schweikert

Neue Zürcher Zeitung –

(…) Rightfully, this new edition received the special award of the German Record Critics' Award 2010

J.-J. Dünki

Darmstädter Echo –

At the International Holiday Courses for New Music in Darmstadt, he was an influential teacher from 193 onwards: Eduard Steuermann, who emphasized precision and pianistic sensitivity in playing. The Darmstadt pianist Erika Haase took courses with him at that time, and it is thanks to her that TACET has now released a double CD featuring Schoenberg's works for solo piano in Steuermann's interpretation, as well as Steuermann's own compositions (a suite and arrangements of pieces by Poulenc, Schubert, and Johann Strauss for two and three pianos). Steuermann plays Schoenberg's pieces just as Schoenberg intended: as romantically sensitive character pieces. While Steuermann's Suite (beautifully played by Thomas Hell) follows in Schoenberg's footsteps, and Steuermann's arrangements show his affinity for the elegant French-Viennese flair, played by the two Darmstadt pianists Erika Haase and Carmen Piazzini, as well as Ulrike Moortgat-Pick. These are consistently rewarding recordings – not just of historical interest. (…)

hz

Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung –

Beautiful, quirky

It's not entirely easy with the piano music of Arnold Schoenberg. Starting with the famous "Three Piano Pieces," in which the composer first completely departed from tonality in 1909, all the important developmental steps can indeed be found first in his works for this instrument—but the music is not loved because of that.

Most performers do not dare to tackle these challenging milestones, which hardly win the favor of listeners. Or do they? On the Tacet label, which has made a name for itself with well-received modern interpretations, historical mono recordings of Schoenberg's pieces have now been released, sounding quite unprecedented: Far from any twelve-tone horrors, the atonal music suddenly resonates with a sensuality and clarity one would never have expected. The pianist who accomplished this miracle is not an unknown, but a great forgotten figure: Eduard Steuermann, born in 1892 in what is now Ukraine, was a pioneer of the Second Viennese School and arguably its most important interpreter. Rediscovering him is akin to rediscovering this previously unloved music.

The Schoenberg recordings are complemented by another perspective on Steuermann: Erika Haase, a student of Steuermann and long-time professor at the Hanover University of Music, together with Thomas Hell and Ulrike Moortgat-Pick, also sheds light on Steuermann as a composer and, above all, as an arranger: a revelation!

Stefan Arndt

Jüdische Zeitung Nr. 54 –

(…) The fact that some of his largely unknown works have now been made accessible to a wide audience is thanks to the Stuttgart-based production company "Tacet." Alongside a carefully reconstructed reissue of his groundbreaking and historically unparalleled 1957 recording of all of Schoenberg's works for solo piano, the double CD released in 2009 also includes a selection of his own piano compositions. These include the "Suite" composed between 1949 and 1951 in the USA, as well as several arrangements of piano works by Francis Poulenc, Johann Strauss, and Franz Schubert. For the first time, one can now gain a nuanced understanding of the famous Schoenberg interpreter by comparing his interpretations with his compositions, revealing a musician who, throughout his life, never found the courage or opportunity to establish his own works in the music world.

(…) Dass die als verschollen geglaubten Aufnahmen nun wieder zusammen mit einer Auswahl an eigenen Kompositionen digital erhältlich sind, macht diese Doppel- CD zu einer überaus lohnenswerten Investition nicht nur für gestandene Musikkenner, sondern auch für all diejenigen, die sich bislang noch nicht an Schönberg herangewagt haben. Unbedingt anhören!

Beate Stender

Süddeutsche Zeitung –

Anyone who wants to discover how much elegance, dreaminess, and (French!) impressionism, how much visionary melancholy and passionately lived uncertainty lies within the music of Arnold Schoenberg must turn to the recordings of pianist Eduard Steuermann (…) Schoenberg, as Steuermann demonstrates, has the ability to describe human existence in transitional situations with just a few notes, where the only thing that matters is the ability to respond to a threatening new situation without denial. A mystery.

Reinhard J. Brembeck

klassik.com –

--> original review

(…) It's wonderful that Eduard Steuermann's recording of the piano works, his Suite for Piano, as well as some of his arrangements of other composers' works, are now accessible again. An informative booklet complements this highly recommendable double CD.

Neue Zeitschrift für Musik –

(…) The very special intensity and conciseness of Schoenberg's piano music could hardly be expressed more compellingly than it is here, and Steuermann's technical virtuosity also shines through, entirely unpretentiously, time and again (…)

Dirk Wiesschollek

Neue Musikzeitung –

(…) And indeed, even today, 53 years later, the recording has lost none of its inner strength and outer fascination. (…) Michael Kube

Falter –

(…) Steuermann's complete recording of Schoenberg's piano works from 1957 was long out of print, and the master tape is lost. Thus, the transfer from a vinyl record now forms the core of a belated "Hommage" on two CDs, supplemented by new recordings of Steuermann's own "Suite" (1951), several arrangements, and a highly informative booklet.

Da ist nicht nur der großartige Pianist Eduard Steuermann mit seinem kultivierten, warmen Ton, seiner expressiven Sanglichkeit neu zu entdecken, sondern auch der „konservative Revolutionär“ Schönberg, gespielt wie mit Blick auf Brahms.

Carsten Fastner

Die Zeit –

The World in One Single Bar

Schoenberg's favorite pianist left behind sensational recordings

"I would very much like to know what has become of Steuermann," writes Alban Berg in September 1914, shortly after the outbreak of World War I, to Arnold Schoenberg. "Steuermann is said to be in Vienna," his teacher and friend writes back. The question of Eduard Steuermann is almost a leitmotif in the correspondence of the Second Viennese School. Born in 1892 in what is now Ukraine, he became the most important pianist of the Schoenberg circle in Vienna and emigrated to the USA in 1938, persecuted as a Jew, where he died in 1964. So, what about Steuermann? He was one of those brilliant intermediaries without whom the new cannot be established. Someone who not only understood what Schoenberg & Co. thought and wrote but played it with such confidence, clarity, and urgency as if the status of the new was long beyond doubt.

He was not burdened by the flaw of many pioneers who mean well but fail to deliver. On the other hand, he was free from the pretense of the star pianist who occasionally lends a hand to a few avant-gardists—after all, he was a composer himself.

The fact that we can hear him again now, in a mono recording from 1957, is valuable in itself — and what we hear truly opens our ears. Steuermann plays Schönberg from the inside out, much more freely, dreamily, and lyrically than the image of the dogmatic taskmaster Arnold would suggest. The pianist guides us from the atonal breakthrough against a Romantic backdrop to the dense yet luminous construct of 1931, having recorded everything his teacher composed for solo piano, apart from a youthful work. A cosmos of modest external dimensions — the pianist needs less than 50 minutes. Yet he knows how much time, world, and life can be contained in a single bar, and through the needle’s eye of the notes, he leads us back into the vastness, where the triad E-B-G# (opus 25) sweeps one away like a gust of yearning into the distance. One could hardly grade the opening of the three pieces opus 11 more finely, nor make it more eloquent or touching. And when Schönberg, as in opus 23, has a line repeated in enlargement, Steuermann casually turns it into a dialogue.

Wherever Eduard Steuermann discovers a musical figure, he brings it to life. It's incredible how differently he can color voices, how vividly he can shape them, and how much space he can open up. For the final piece of opus 19, Schönberg’s last greeting to Gustav Mahler, Steuermann needs only 59 seconds — and within them, he reaches greater depths than, for example, Mitsuko Uchida, who drowns the movement in a pathos-laden two and a half minutes and excessive pedal.

The fact that we can hear Steuermann again is thanks to a project by the Tacet label, which also presents him in new recordings as a composer. Yet even there, he is at his strongest when interpreting — as an arranger. In Wohin?, from Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin, Erika Haase, Carmen Piazzini, and Ulrike Moortgat-Pick sit at three pianos: the German forest of mill wheels in G major disappears, and instead, in G-flat major, a transatlantic river delta sparkles through towering roots. Rarely has anyone discovered more horizon behind the notes.

Volker Hagedorn

Fono Forum –

Fono Forum Tipp

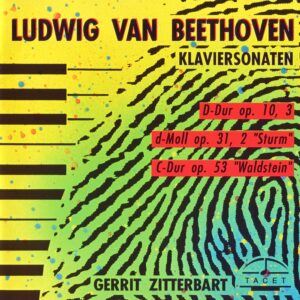

Splendid Homage

"How wonderful that Steuermann’s recording of Schönberg’s piano pieces is finally available again; it remains the classical benchmark for interpreting these works." The praise on the album cover of this tribute comes from an authoritative source — Alfred Brendel, who himself took piano lessons with Eduard Steuermann. The newly reissued recording of Schönberg’s solo piano works was originally made by Steuermann in 1957 for American Columbia. Andreas Spreer has now transferred the historical mono recordings from an LP and carefully restored them, achieving a surprisingly excellent result.

Steuermann’s recordings of Schönberg possess a particular authenticity, as Steuermann (1892–1964) had studied with Arnold Schönberg in Berlin from 1912 onward, later following him to Vienna, where he became the leading pianist of the Schönberg circle. Steuermann’s approach to Schönberg is, in the truest sense of the word, “classical.” The ideal of textual fidelity that Alfred Brendel would later realize in the classical-romantic repertoire is already exemplarily fulfilled in Steuermann’s interpretations of Schönberg. If one compares his interpretation of the *Six Little Piano Pieces*, Op. 19, with that of Glenn Gould — who also became a strong advocate for Schönberg’s music from the 1950s onward — it is striking how meticulously Steuermann plays, even in rendering the finely detailed dynamic instructions Schönberg notated. By contrast, Gould’s interpretation appears almost extravagant, at times articulating against the score and ignoring Schönberg’s dynamic markings. Steuermann presents Schönberg’s bold constructions with great straightforwardness and directness — but without sounding any less expressionistic than Gould’s somewhat more sonically indulgent reading.

The second CD honors Eduard Steuermann as a composer, featuring works of very different stylistic character. Steuermann’s Suite for Piano, composed between 1949 and 1951, refers to the model of the Baroque suite only in the title of its first movement, “Prelude”; otherwise, it is a collection of character pieces, as suggested by movement titles such as “Melody,” “Misterioso,” “Chorale,” and “March.” Steuermann’s deep admiration for Schönberg is clearly audible throughout. Thomas Hell interprets this expressionistic music with great intensity.

A completely different side of Steuermann — a light-hearted and entertaining one — is revealed in his arrangements for two and three pianos. Erika Haase, Carmen Piazzini — and, in the arrangements for three pianos, Ulrike Moortgat-Pick as well — perform them with verve and a keen sense of sound. The centerpiece is the more than 17-minute-long Paraphrase on Themes from Johann Strauss’s "Die Fledermaus", in which Haase and Piazzini luxuriate delightfully in the three-quarter time. Strauss’s two-minute Perpetuum mobile, also arranged for two pianos, comes across as spirited and exuberant. Poulenc’s Toccata — originally composed for two pianos — is thrillingly intensified by Steuermann in his version for three pianos through the addition of numerous secondary voices. Schubert’s Wohin?, by contrast, remains relatively simple in character, despite the division of the texture across three pianos.

Erika Haase has contributed a brief remembrance of her former teacher to the booklet. In addition, Russell Sherman pays tribute to his former teacher and Michael Gielen to his uncle — both, of course, Eduard Steuermann. Also noteworthy are the more extensive essay by Volker Rülke and Steuermann’s own analysis of Schönberg’s piano music. An exceptionally successful tribute.

Gregor Willmes

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

Exemplar Recordings

The Stuttgart label Tacet honors the distinguished Schönberg pianist Eduard Steuermann.

Arnold Schönberg insisted that he was not writing twelve-tone music, but rather Twelve-Tone Music. What this means can now be understood through a CD that makes Steuermann’s 1957 complete recording of Schönberg’s groundbreaking piano works available again. Steuermann, a student of Busoni as a pianist and of Schönberg as a composer, was particularly close to the master throughout his life.

What we hear are model recordings beyond any dogmatic rigidity. Steuermann plays Schönberg’s five piano works, which trace the development from the expressionism of free atonality to the masterful command of serial technique, with meticulous text-analytical precision — uncompromising yet nuanced, with subtle inflections. He emphasizes clarity of musical logic and transparency of formal structure, while also highlighting cantabile phrasing. Even the often dry-sounding Suite Op. 25, with its reference to Baroque forms, is brought to life by his wonderful espressivo touch and warm sound. Above all, it is this seamless unity of intellectual control and artistic sensitivity that makes Steuermann’s playing an invaluable school of thought in new music.

The reissue is supplemented by selected works and transcriptions by the composer Steuermann. The Piano Suite, performed by Thomas Hell, establishes him as an independent representative of the Schönberg school, one who skillfully combines the principles of his mentor with Romantic coloration. Among the transcriptions for two or three pianos, the lively Paraphrase on "Die Fledermaus" stands out. This arrangement, which departs significantly from the original, demonstrates how seriously Steuermann took the commitment to perform new music in the spirit of the old. As his piano student Adorno put it, he was a “secretly righteous figure of music” and a great interpreter.

Uwe Schweikert

Audiophile Audition –

An important and influential recording comes back to light, though Sony is probably sitting on the original tape.

I did not know about the musical exploits of Eduard Steuermann before seeing this release. Actually, his name is on an edition of Brahms’s piano music as editor—perhaps some of our readers have that edition—and apparently he was of such temperament that a performing career was not in the cards. Nevertheless, he did make some recordings—of which this and a Busoni album are the only ones extant—and as a dedicated student and disciple of Schoenberg who knew the man very well, this album of the complete music for solo piano has a great deal of importance.

As a pianist of an older age it is instructive to see how he approaches these seminal serial works. All are atonal—the Op. 11 marks the first composition of complete tonal freedom of the composer—and Steuermann does take a more analytical, finely-honed trail through these pieces. For example, the opening of the baroque suite known as Op. 25, Steuermann is far more romantic in approach that Jacobs or Pollini, and not so much attuned to the idea of any of the piano lines as exemplifying a “melody” the way these others do; at the same time, his tonal palate - fairly restricted in this music - is quite broad and orchestral with a much wider dynamic range than others.

Steuermann‘s own Suite recorded here is interesting, even likeable, but despite the adulation given to his music by Theodore Adorno listed in the booklet, remains second rate Schoenberg (the pianist himself spoke of how impossible it was to compose anything in the presence of Schoenberg’s overwhelmingly dominant range of personality). The arrangements for two and three pianos are entertaining and nicely done, but not essential—the Schoenberg is.

I noticed a certain distortion in some of the louder passages of the Schoenberg, a recording initially released by American Columbia Records in 1957 (and in mono) before reading in the notes "unfortunately the original tape of the historic mono Steuermann recording was not available. It seems to be lost. Instead of that an original 33 1/3 rpm LP was transferred, restaured [sic] by hand and with the help of latest restauration [sic] software." Right. I know exactly what happened—it’s probably still locked in the depths of the Sony vaults where half of the world’s recorded classical music treasures still languish, like the Ark in the last scene of Raiders of the Lost Ark. When will they get off their brains and open this stuff up to music lovers?

This at least explains the distortion. But this is an excellent LP transfer with a wide sonic range and clear clean mono sound. The other CD was recorded last year and sounds just fine. As an important document, wonderful performances, and especially for Schoenberg fans, urgently recommended.

Steven Ritter

Piano News 2/10 –

Many — even piano enthusiasts — will first ask: Who is Eduard Steuermann? Unfortunately, the name of this versatile pianist and composer has nearly been forgotten. This is all the more surprising, given the immense impact he had on the musical landscape of his time. Born in 1892 in Sambor, Galicia (now Ukraine), he received his first piano lessons from his mother before going to Lviv to study with the Busoni student Vilem Kurz. Ultimately, he received his final training from Ferruccio Busoni himself in Berlin. When he met Arnold Schönberg in 1912, it was a defining encounter for him. He would go on to become the most important pianist of the entire Schönberg school, moving to Vienna after World War I, where he forged friendships with Rudolf Kolisch and Theodor W. Adorno, who studied piano with him. He was also a key pianist in the "Society for Private Musical Performances," founded by Schönberg. Over time, he made a name for himself as a pianist. When the Nazis seized power in Europe, he reluctantly emigrated to the United States and settled in New York, where he took a professorship at the Juilliard School of Music and taught renowned pianists such as Jerome Lowenthal and Russell Sherman. He passed away in New York in 1964.

The "Hommage" now available from TACET consists of two CDs that shed light on Steuermann in different ways. First, there is a CD featuring all of Schönberg’s piano works in Steuermann’s interpretation. And it quickly becomes apparent how much sensuality Steuermann brings to these works. Whether in the early Piano Pieces Op. 11 or the Piano Pieces from Op. 19, his touch is unmistakable. Even in the Piano Pieces Op. 23, he finds lyrical phrasing that challenges the stereotype of Schönberg as a purely constructive composer. However, from the Suite Op. 25 onwards, Schönberg’s musical language changes, already bound by the idea of twelve-tone technique. Steuermann comes across as a brilliant pianist, having recorded these works in 1957.

The second CD presents works by the composer Eduard Steuermann, providing the listener with a comprehensive portrait of this fascinating musician. Thomas Hell performs his Suite, and naturally, the musical language is very similar to that of Schönberg, although Steuermann — being a true pianist — expands the range of sound even further than his teacher Schönberg. Nevertheless, the bond between teacher and student is undeniable, even though one would be reluctant to accuse Steuermann of mere epigonism. Erika Haase, who attended courses with Steuermann in Darmstadt, and Carmen Piazzini then perform Steuermann’s Johann Strauss arrangements for two pianos, including those from Die Fledermaus as well as the Perpetuum mobile. Here, his work is at least as exhilarating as Schönberg’s arrangement of Strauss’ Rote Rosen for chamber orchestra. The two pianists are later joined by Ulrike Moortgat-Pick, who plays the third piano, to perform Poulenc’s Toccata and Schubert’s Wohin?. All three pianists clearly revel in the joy and excitement of this music.

This tribute is a wonderful opportunity to remember the pianist and composer Eduard Steuermann or to become acquainted with him for the first time.

Carsten Dürer

Neue Musikzeitung 3/10 –

Andreas Spreer of the TACET label presents a historically significant document of the highest order on a double CD: the complete recording of Schönberg’s piano pieces, recorded in 1957 by Eduard Steuermann, a key interpreter of the Viennese School since 1919.

Die von einer originalen Mono-LP übertragenen,vorbildlich restaurierten Aufnahmen ergeben ein absolut klares Bild von Steuermanns Interpretation, die als authentisch bezeichnet werden kann. Er spielt transparent, mit elastischer, die Sinneinheiten deutlich gliedernder Phrasierung und in einem Tempo, das nie überhastet wirkt und alle Details hörbar werden lässt. Die zweite CD enthält eine Suite des Komponisten Steuermann sowie seine Bearbeitungen von Werken von Johann Strauß, Schubert und Poulenc in einer Produktion von 2009. Mit den von einem instruktiven Booklet begleiteten Aufnahmen lernt man einen Protagonisten der Moderne kennen, dessen ästhetische Auffassungen noch ganz selbstverständlich in der Tradition verankert waren.

Max Nyffeler

Schweizer Radio DRS –

"...a rarity and a sensation."

99 years ago, on May 18, 1911, Gustav Mahler died in Vienna. A month later, Arnold Schönberg wrote a musical tombstone for Gustav Mahler, a short piano piece lasting 59 seconds. Schönberg filtered the symphonic, boundless nature, the sounds of nature, and the dissonances of Mahler's music, essentially distilling them into fifths — only fragments and ruins are left, tombstones, indeed. 53 years ago — in 1957 — Eduard Steuermann recorded this piece, one of the very rare recordings that exist of Steuermann. It's almost a scandal, as the late Eduard Steuermann (who died in 1964) was one of the most influential and innovative pianists of the 20th century and was regarded as THE Schönberg interpreter. This rarity has now been transferred from an LP and restored: an acoustic glimpse back into the early 20th century of unparalleled music-historical value. And Steuermann's interpretation of Mahler’s tombstone is simply a sensation: the delicacy of the high register, the lostness of the melodic fragments, the relentlessness in the depth of the grave.

Arnold Schönberg, Opus 19, No. 6, played by Eduard Steuermann: 59 seconds of music in pianissimo tell the entire life of an artist.

Cécile Olshausen

SWR2 Neues vom Klassikmarkt –

The aforementioned "Society for Private Musical Performances," founded by Schönberg, had a brilliant pianist and composer who participated in almost all performances: Eduard Steuermann, a Galician Jew who had to emigrate to the USA in 1938, where he — as "Edward Steuermann" — became a legendary teacher of piano and composition. Before that, he had studied these subjects in Berlin — with Ferruccio Busoni and Arnold Schönberg. A new double CD from the Tacet label has now released the legacy of Eduard Steuermann — featuring his phenomenal recordings of Schönberg's piano works, and on CD 2, new recordings of his strictly twelve-tone but very colorful and distinctive Suite for Solo Piano from 1951. The rest of this disc features world premiere recordings of equally colorful arrangements for two or three pianos, of works by Francis Poulenc, Johann Strauss Jr., and Franz Schubert. The themes from Die Fledermaus, performed by the initiator of the release, Erika Haase, and Carmen Piazzini, are especially pointed. The piece lasts over 17 minutes, so I can only play you the first five minutes, but as Mozart always demanded, it is a great pleasure for connoisseurs. It would have fit perfectly into the "Society for Private Musical Performances"...

(…)

This double CD release from the Tacet label is also a gem: It is titled Hommage à Steuermann and offers not only his legendary recordings of Arnold Schönberg's solo piano works, but also one of the pianist’s own compositions, the Suite from 1951, as well as some very witty or deeply touching transcriptions by Eduard Steuermann. For example, the song Wohin? from Schubert’s Die schöne Müllerin, arranged for three pianos.

Thomas Rübenacker

Frankfurter Rundschau –

A remembrance of a completion

A tribute to Eduard Steuermann, pianist and composer of the Schönberg circle.

From New York to Darmstadt, it was only a short journey around 1960. The pull of the "Summer Courses for New Music" also attracted the celebrities of the emigration, including Eduard Steuermann, the most prominent pianist of the Schönberg circle, now a revered teacher at Juilliard. Steuermann's teachings opened up insights into a compositional sphere that was free from dogmatic rigidities.

Participation in one of the most important signs of modernist breakthroughs also included respect for the tradition of "great music." With this dual perspective, artists like Steuermann were little aligned with the rigid self-assertion of those building anew on scorched earth. The cultivated, integrative nature of Steuermann’s artistry, which in its resoluteness also exhibited a kind of gentleness and hesitation, made him seem unappealing in a phase dominated by the shrill self-representations of others.

Today, there is perhaps a greater appreciation for nuances and for an interpretive mastery that is far from being polished or boring; rather, it stems from the deepest understanding of musical phenomena. The analytical ability never comes across as intrusive; the work on tonal clarity takes on a sense of naturalness, almost casualness. When listening to Steuermann's interpretations of Schönberg's piano works, which are considered classical, one inevitably thinks of the notion of the "conservative revolutionary." In Steuermann’s playing, the expressionistic gestures of the music do not become independent; they seem rather Brahmsian, embedded in a line that is guided by a secret cantability.

Under the influence of the serialists, a version of Schönberg emerged that was more defined by cool constructivism, far removed from his Viennese aspects. Steuermann, however, clearly belonged to the Viennese faction of Schönbergians. Born in 1892 in Sambor (today in Ukraine), he first came into contact with the circle of Ferruccio Busoni, and only later with Schönberg, whose personality captivated him for life— in a decidedly ambivalent way, which is not surprising given the authoritarian nature of the figure. In 1936, Steuermann went into American exile; he died in 1964 in New York. After strict twelve-tone work, he found solace in the Viennese musical gods. Naturally, Steuermann’s impressions from the early years of the summer courses remained alive not only in Darmstadt. But it seems no coincidence that a revival initiative of Steuermann's art came primarily from a Darmstadt pianist—Erika Haase, who, in addition to contributing her memories of Steuermann's teachings, also helped, with special editorial effort, to bring the much-anticipated and now enthusiastically received disc edition, which was eagerly awaited by Theodor W. Adorno and embraced by musicians like Michael Gielen and Alfred Brendel, to fruition.

A central component of the recently released CD project is the complete recording of Schönberg’s piano works, which was made in 1957 for Columbia and has long been unavailable (it fit comfortably on a single LP). The original mono tape seems to be lost; the current CD results from a skillful LP transfer. The sound quality is vivid and authentic. It particularly conveys the warm timbre that is characteristic of Steuermann, despite his sparing use of the pedal.

Exploring Steuermann’s extensive compositional output would, in the future, be the task of philologically driven discovering interpreters, such as Kolja Lessing or Herbert Hencks. Nevertheless, the Hamburg-born Thomas Hell, who can be described as a pianist who, despite temporal distance, is very close to Steuermann’s aesthetic intentions, gives a significant sample of Steuermann’s own compositional work with the Suite for Piano, composed between 1949 and 1951. Unlike in the twelve-tone Schönberg Piano Suite Op. 25, there is no neoclassical reference here; the movement titles are more akin to character pieces in the style of Schumann or Brahms – a small perspective shift that is indicative of the independence of this Schönberg disciple.

More than half of this second CD is dedicated to Steuermann’s arrangements for two and three pianos. This alludes to the hedonistic trend within the Schönberg school, which, after rigorous twelve-tone work, liked to unwind with Viennese “house gods” like Johann Strauss and Schubert. In this Steuermann homage, the music is, in a sublimely opulent and sometimes playful way, just as captivating. Erika Haase, Carmen Piazzini, and Ulrike Moortgat-Pick perform the Strauss paraphrases "Themes from Die Fledermaus" or Poulenc's Toccata (with a witty fireworks display of newly invented motifs and counterpoints) and give Schubert's Müllerlied "Wohin" a new, purely instrumental urgency.

But again and again, one happily returns to Steuermann's Schönberg album with its interpretations that are far from abstract or technicist. For this, Steuermann also wrote his own commentary, which, despite its objectivity, carries a personal touch. In it, he says only a few words about the Suite Opus 25, composed in the established twelve-tone technique. However, he is much more detailed in his remarks about the five Piano Pieces Opus 23 and their somewhat twisted path into the new compositional technique. Yet another Steuermann paradox: the "journey" seems to have interested this master of completion and fulfillment even more than the arrival itself.

Hans-Klaus Jungheinrich