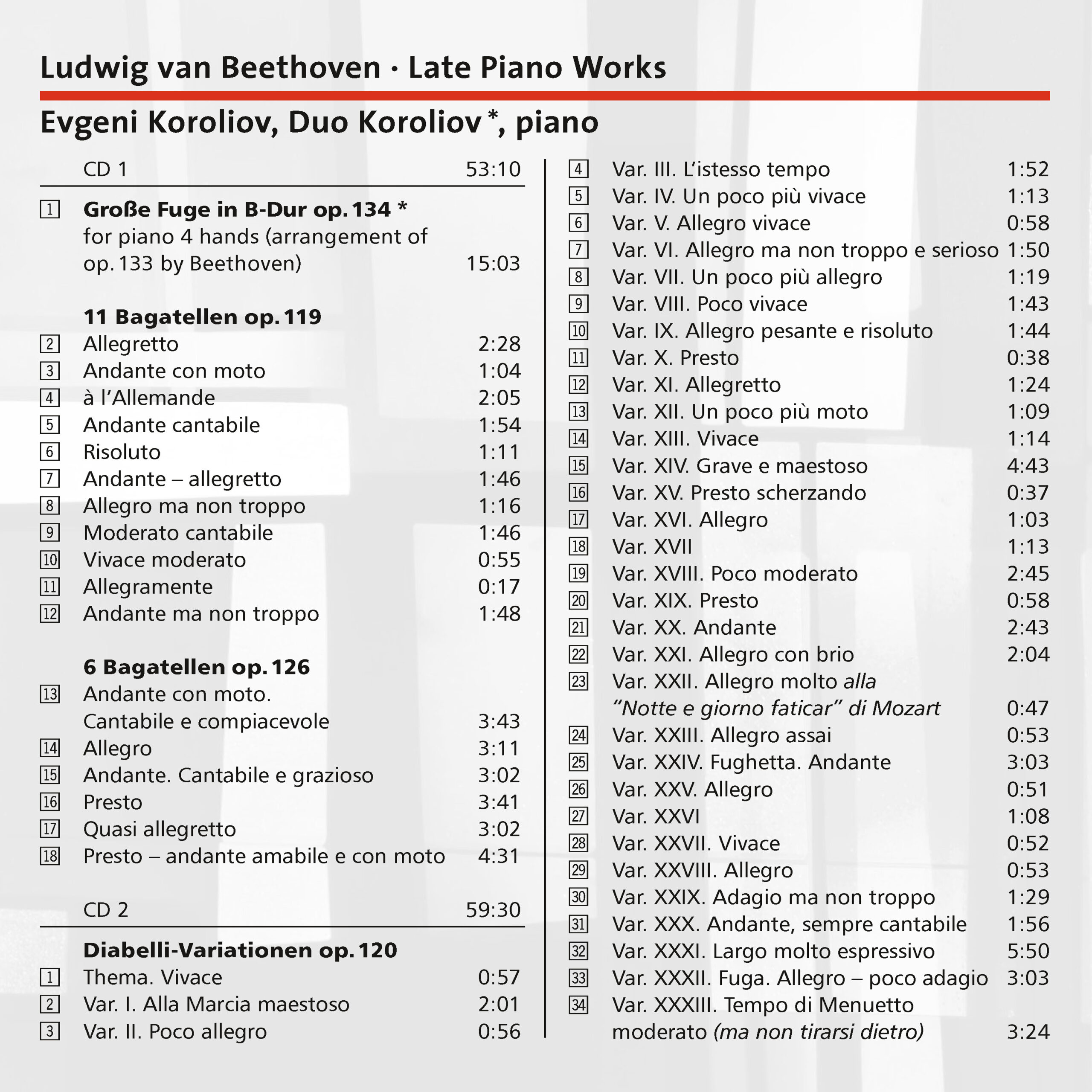

228 CD / The Koroliov Series Vol. XX. Late Piano Works by Ludwig van Beethoven

Description

Although Beethoven's opus numbers extend to op. 135, there were no more piano sonatas after op. 111. There is, though, a variation cycle lasting almost an hour on a simple theme by Anton Diabelli. This astonishing cycle takes the listener into such distant moods, that even after the first variation it doesn't matter what the theme is, it is all so unmistakably Beethoven. Also on this disc, two cycles of "simple" piano pieces entitled "Bagatelles". Small, unimportant things, trivialities, which make you think involuntarily of much later romantic composers. And finally, the usually so self-critical Beethoven allocated his penultimate opus number (op. 134) to a "simple" piano score of the "Große Fuge" op. 133! So how does all this fit together?

Obviously, the scope of classical forms was too narrow for Beethoven. Did this apparent simplicity serve a wider purpose? The very last movement of the very last opus, the string quartet op. 135, is based on the text "Must it be? - It must be! " Was Beethoven in his last works pursuing an overall objective? Or did it all just happen like that? Find out now! You can find these last works for piano alongside each other on a double CD.

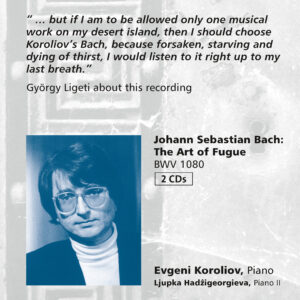

Just listen to the first few seconds of the "Große Fuge" with Ljupka Hadzigeorgiewa and Evgeni Koroliov. Succumb to the charm and allure of these two musicians, who lead us selflessly and confidently through this perplexing hiatus in musical history.

7 reviews for 228 CD / The Koroliov Series Vol. XX. Late Piano Works by Ludwig van Beethoven

You must be logged in to post a review.

Fanfare –

--> original review

Ein großer Teil meiner Schreibarbeit in diesen Seiten legt eine gewisse Ungeduld gegenüber neuen Aufnahmen des Standardrepertoires nahe. Oft schreibe ich, dass es in einer Sammlung, die legendäre Aufnahmen dieser Werke enthält, keinen Platz für eine mittelmäßige Aufnahme der kanonischen Werke gibt. Der „überfüllte Bibliothek“ -Test scheint jede neue Aufnahme eines alten „Kriegspferds“ auszuschließen; schließlich, wer unter den heutigen Beethoven-Interpreten kann einer Schnabel oder Richter das Wasser reichen? Trotzdem glaube ich nicht, dass das letzte Wort in der Beethoven-Interpretation gesprochen wurde. Tatsächlich glaube ich bei Musik so reichhaltig wie Beethovens oder eines wirklich großen Komponisten nicht, dass es ein endgültiges Wort geben kann, und meine Sammlung kann Platz für viele weitere Aufnahmen solcher Werke machen – vorausgesetzt, der Interpret erfasst die Tiefe der Musik und bringt eine einzigartige, reife künstlerische Persönlichkeit ein. Wenn ein Künstler dies tut, wie es Evgeni Koroliov in diesem 20. Band seiner Aufnahmen für Tacet tut, sind Vergleiche mit historischen Pianisten sinnlos. Koroliovs Beethoven klingt nicht wie Brendels oder Schnabels; es klingt nach Koroliov – und in diesem Fall bedeutet diese tautologische Aussage tatsächlich etwas.

There is nothing grossly different between Koroliov's interpretations and those that have entered the canon; the difference lies in the subtleties, not in having discovered anything revelatory about Beethoven's music, with one fascinating exception. Most pianists interpret the 16th note passages that begin the second of the Op. 126 Bagatelles as a Bachian toccata. Koroliov's touch is heavier and his tempo faster than most here, creating a whirlwind of Beethovenian fury similar to some of the cacophonous passages in the Ninth Symphony. The standard interpretation has always pleased me as a final statement, as if Beethoven, at the end of his career, was reflecting on how his music was derivative of the previous era. Koroliov's interpretation seems to look forward, progressing through extremes of sound that Beethoven had barely begun to explore.

The hallmark of Koroliov's playing is its subtle, conversational element. His phrases breathe with barely perceptible freedom. He rarely lingers operatically on a high note or speeds up through climactic passages, but close listening reveals that his tempo is in a state of constant but barely perceptible fluctuation, creating the illusion of absolute evenness while avoiding the stiffness of literally playing evenly. And Koroliov's occasional slight hesitations or impulsive bursts of speed are elegant, refreshing subtleties. Consider, for example, the variety of emphasis he gives to the triplet figuration in the second of the Op. 119 Bagatelles. Richter's treatment of this trivial matter is entirely elegant; Brendels is breathless and rushed. But Koroliov creates a conversation between treble and bass figuration: some passages are almost shy, some are boisterous, and each responds to the other. Or consider Koroliov's insistent ritardando at the start of the 11th Diabelli Variation as the music prepares to pause on the dominant. Richter plays the passage almost without inflection; Koroliov emphasizes the pause, and Beethoven's sudden continuation of the harmonic movement takes on the aspect of a decisive answer to an implied question. In this way, Koroliov acts both expressively as an interpreter of the content in Beethoven's music and analytically as a guide through the structure of Beethoven's music. This dual role is evident in his meticulous treatment of the imitative entries in the Fourth Diabelli Variation: the lines are clear throughout, but Koroliov does not pedantically announce each entry; instead he caresses it as each new voice adds to the warmth of the variation.

My overall reaction to Koroliov's playing is extremely enthusiastic. And this despite occasional weaknesses in its execution. At louder volumes, his melodic accents can be harsh in tone. His rubato, which I consider to be one of his greatest strengths overall, is not always successful; The fifth of the Op. 126 Bagatelles is uneven in both tempo and dynamic shading. And his interaction with four-hand partner Ljupka Hadžigeorgieva is a matter of luck: some of the imposing chords at the beginning of the Great Fugue simply don't belong together, although the much trickier unisons towards the end of the piece are flawlessly coordinated. In their interpretation they capture the reflective depth of the piece's more generous sections, but its more forceful statements strike me as too percussive.

The sound engineering is excellent throughout, with the caveat that the recording location is not identified in the liner notes and must have been near a busy street and a playground or a school. A significant number of car tires made it into the recording, including one that is distinct enough to sound like a pedal tone in the closing Op. 119 Bagatelle. And the sounds of children playing are present in the pauses before the end of tracks in several instances. All in all, I strongly recommend this recording. Koroliov has delivered a truly individual and entirely serious interpretation of these important works.

Myron Silberstein

Artamag –

--> original review

Record of the Day

(…) This quite fabulous album opens with the Great Fugue as Beethoven transcribed it for his instrument, an inextinguishable work where Koroliov finds Ljupka Hadzi-Georgieva: reading on the Dantesque escarpments.v

Erhabene Tonaufnahme, wie immer bei Tacet, einem der wenigen Phonographieverleger, der weiß, wie man Klavier aufnimmt.

Jean-Charles Hoffélé, Artamag

_________________________________________________

Le Disque du jour

(…) Cet album assez fabuleux s’ouvre par la Grande Fugue comme Beethoven l’a transcrite pour son instrument, œuvre inextinguible où Koroliov retrouve Ljupka Hadzi-Georgieva : lecture aux escarpements dantesques.

Prise de son sublime, comme toujours chez Tacet, l’un des rares éditeurs phonographiques qui sache enregistrer le piano.

Jean-Charles Hoffelé

Image Hifi –

(…) The Great Fugue op. 133 has the aura of a brilliant, inaccessible late work for string quartets. Beethoven himself created a version for piano four hands. The Duo Koroliov argues for this opus 134 in a pianistically impressive recording. What remains of the Great Fugue if it is no longer played by four strings but by two pianists on a concert grand? Less color, less individuality in the voices – like the ink drawing of a painting, pure structure. That doesn't make it any easier for us listeners. In the further program of the double CD, Evgeni Koroliov plays the Bagatelles op. 119 and op. 126 as well as the Diabelli Variations op. 120 (Beethoven's last great piano work). Koroliov fans know: this master rarely plays excitingly. Here too, in self-forgetful concentration, he presents the essence of the music in his own way - committed only to the musical text and the beauty. Sometimes, for example in the Andante cantabile from op. 119, a gentle, longing mood emerges, which brings Beethoven close to Schubert. A delightful Koroliov recording with excellent sound. (…)

Heinz Gelking, image hifi

Piano News –

Was hat dieser grandiose russische Pianist nicht schon alles für TACET eingespielt – Bach, Schubert, Mozart – etliche der Standardliteratur hat er in seinen Interpretationen mit neuem Leben versehen. Nun spielt er die letzten Klavierwerke aus der Feder Beethovens, die „Große Fuge“ op. 134 im Arrangement für vier Hände (mit seiner Ehefrau Ljupka Hadzigeorgieva), die Bagatellen op. 119 und op. 126 sowie die „Diabelli-Variationen“.

The Diabelli Variations now show Koroliov's entire view of a work: on the one hand, he presents the theme and variations with vehemence, but also with enormous rigor when it comes to rhythm and accents. Nothing is treated shallowly or superficially. Koroliov gets to the bottom of the variations and her own energy and treatment of the theme, knowing how to give every nuance its due. With this musical interpretation it would be presumptuous to say that Koroliov lets the music speak for itself, but that is exactly the impression you get because he doesn't take himself any more seriously as a pianist than the musical text. In this way, exactly what every musician is looking for is achieved: the greatest possible truth in the interpretation of the work. And that's exactly the impression you get when listening to these recordings - with overall quite healthy tempos. The Russian is able to shape the structural impact of this music, the ever-present modernity, in such a natural way that one often listens in amazement - and wonders why others, who also follow the musical text, are not able to interpret this from constant ones Alternating, interwoven drama to create the intensity that Beethoven left behind in notes.

The two Bagatelle cycles, on the other hand, are designed to be much more personal: Koroliov goes even further out of himself here, makes it more direct and personal, lets it bubble and tingle, knows how to make the beautiful and yet complex simplicity sound in such a way that the listener indulges and smiles , but also always listening attentively to the little things that the pianist lets you hear.

These CDs already have cult and reference status and once again prove the importance of Evgeni Koroliov.

Piano News

Diapason Magazine –

For his twentieth volume with Tacet, Evgeni Koroliov focuses on Beethoven's late opuses – two years after an album bringing together the last three sonatas. Her Diabelli are the most consistently beautiful we know. The path taken by Koroliov is that of an aesthete, who does not seek to exalt the conflicts of writing but enjoys its perpetual renewal. Such tranquility can certainly be confusing in this work. Koroliov takes the time for poetic abandon where others play the card of heroic arrogance, playful impatience or excess.

His artist signature? A subtle retention of phrasing, slight inertia that he drags behind him. If the expressive range may seem restricted, we quickly realize that it is this constancy of tone that seduces. The pianist addresses a serene prayer, with each variation more penetrating. His Diabellis, however, dare modernism (Variation XVII) going so far as to draw aquatic worlds (XXI). A master of sparkling virtuosity (XXVII), Koroliov masks nothing with pretense: risks are taken where they must be (X, XVI). The hand that traces the different voices of the Fughetta (XXIV) knows how to be tender and loving, like projecting us into the purest state of grace (XXXI). Partial reading? And assumed as such. These Diabelli have the effect of a fresh shower.

We can step over, in the complements, a Grande Fugue (four hands) whose incisive rhythm forces a certain hardness. Before being liquefied on the spot by the two opuses of Bagatelles, of disarming beauty. The creation of the harmonic diagram and the digital execution are superlative.

As always in this “Koroliov series”, the high notes of the piano radiate an impalpable, magical and precious light. In sound, this Beethoven is as seductive as Kempff, with the same perfection of modeling, and throughout a sound curve that so many modern readings neglect or ignore.

Julien Hanck, Diapason Magazine

______________________________________________________

Pour son vingtième volume chez Tacet, Evgeni Koroliov s’attache aux opus tardifs de Beethoven – deux ans après un album regroupant les trois dernières sonates. Ses Diabelli sont les plus constamment belles que nous connaissons. Le chemin emprunté par Koroliov est celui d’un esthète, qui ne cherche pas à exalter les conflits de l’écriture mais jouit de son renouvellement perpétuel. Une telle quiétude peut certes dérouter dans cette oeuvre. Koroliov prend le temps de l’abandon poétique là ou d’autres jouent la carte de l’arrogance héroïque, de l’impatience ludique ou de la démesure.

Sa signature d’artiste ? Une subtile rétention de phrasé, légère inertie qu’il traîne derrière lui. Si l’ambitus expressif peut paraître restreint, on s’aperçoit vite que c’est cette constance de ton qui séduit. Le pianiste adresse là une prière sereine, à chaque variation plus pénétrante. Ses Diabelli osent pourtant le modernisme (Variation XVII) allant jusqu’à dessiner des mondes aquatiques (XXI). Maître d’une pétillante virtuosité (XXVII), Koroliov ne masque rien par des faux-semblants : les risques sont pris là où ils doivent l’être (X, XVI). La main qui trace les différentes voix de la Fughetta (XXIV) sait être tendre et aimante, comme nous projeter dans le plus pur état de grâce (XXXI). Lecture partiale ? Et assumée comme telle. Ces Diabelli font l’effet d’une douche fraîche.

On peut enjamber, dans les compléments, une Grande Fugue (à quatre mains) dont la rythmique incisive contraint à une certaine dureté. Avant d’être liquéfié sur place par les deux opus de Bagatelles, d’une désarmante beauté. La réalisation du schéma harmonique, l’exécution digitale y sont superlatives.

Comme toujours dans cette « série Koroliov », les aigus du piano rayonnent d’une impalpable lumière, magique et précieuse. En sonorité, ce Beethoven-là est aussi séduisant que du Kempff, avec la même perfection du modelé, et partout un galbe sonore que tant de lectures modernes négligent ou ignorent.

Julien Hanck, Diapason Magazine

Audio –

Auf Vol. XX seiner Edition präsentiert der in Hamburg lebende russische Pianist Evgeni Koroliov die letzten Kompositionen Ludwig van Beethovens für Klavier. Diese gehören zum Höchsten und Schwersten, was ein Pianist bewältigen kann. Wieder einmal besticht Koroliov durch seine künstlerische Integrität, die die kleinformatigen Bagatellen op. 119 und op. 126 ebenso durchdringt wie das Opus Magnum, die Diabelli-Variationen op. 120 und die „Große Fuge“ op. 134, von Beethoven für vier Hände bearbeitet und vom Ehepaar Koroliov ausgeführt. Ein Extra-Lob für das schöne Klangbild: Ganz genau so sollte ein Klavier aus den Lautsprechern klingen.

Andreas Luczewicz, Audio

Klassik heute –

--> original review

Evgeni Koroliov is certainly one of the most serious, unwaveringly disciplined interpreters, even in highly expressive moments, not only in the pianistic world today, but also in the entire scene since the possibility of recording has existed. In this respect, I was very curious to see how this model of precision and musical moral harmlessness would deal with Beethoven's Bagatelles. Especially with the often capricious, lively 11 Bagatelles op. 119, which are paid much less attention by interpreters, not only today, than the later op But he also shows himself to be overconfident, that is, under these circumstances: he certainly seems to be open to a humorous variety, a piano-cabaret touch, so to speak, and to force it (or take it back) with his very own means of irrefutable diction. Under these circumstances, these miniatures can be experienced as important music, but at the same time as experimental bycatch in the composer's compositional dragnet.

Although the six Bagatelles op. 126 were written later than the Diabelli Variations op. 120, one could suspect that these “Bunten Blatten” were a creative piano gymnastics in advance of the monumental Diabelli exaggeration. The placement of the bagatelles at the end of the first CD and thus in the run-up to the second CD with the Diabelli cycle sets this somewhat misleading track, especially if the listener sticks to the sequence of works given by Tacet.

With the Diabelli Variations, Evgeni Koroliov proves himself to be a master of sifting through, grading, bundling and examining individual and closely related variation models. He takes the topic seriously, plays it without exaggerated accents, without ironic nuances, and certainly not in such an overly sentimental way as Sokolov. Koroliov acts fundamentally strictly, but elastically in his own way, with a great willingness to savor the melodically paused, even hesitant variations in all exciting calm, whereby he always manages to connect what has come before with the illusion of what is to come.

The first CD opens with the piano duo version of the Great Fugue op. 134. In my opinion it is the most vivid, so to speak “understandable” of all the representations available to me. A nice lesson in how one can bring the academic aspects of a fugal idea close to intellectual entertainment. Evgeni Koroliov once again presents his wife Ljupka Hadzigeorgieva, who comes from Macedonia. It corresponds to a trend of the last few years, even decades, because quite a few well-known pianists appear with their wives, or at least they encourage the organizers to accept at least a family element in their solo concerts. I'm thinking of Dezsö Ránki and Edit Klukon, Robert Levin and Ya-Fei Chuang, Herbert Schuch and Gülru Ensari - to name just three such formations.

Peter Cossé