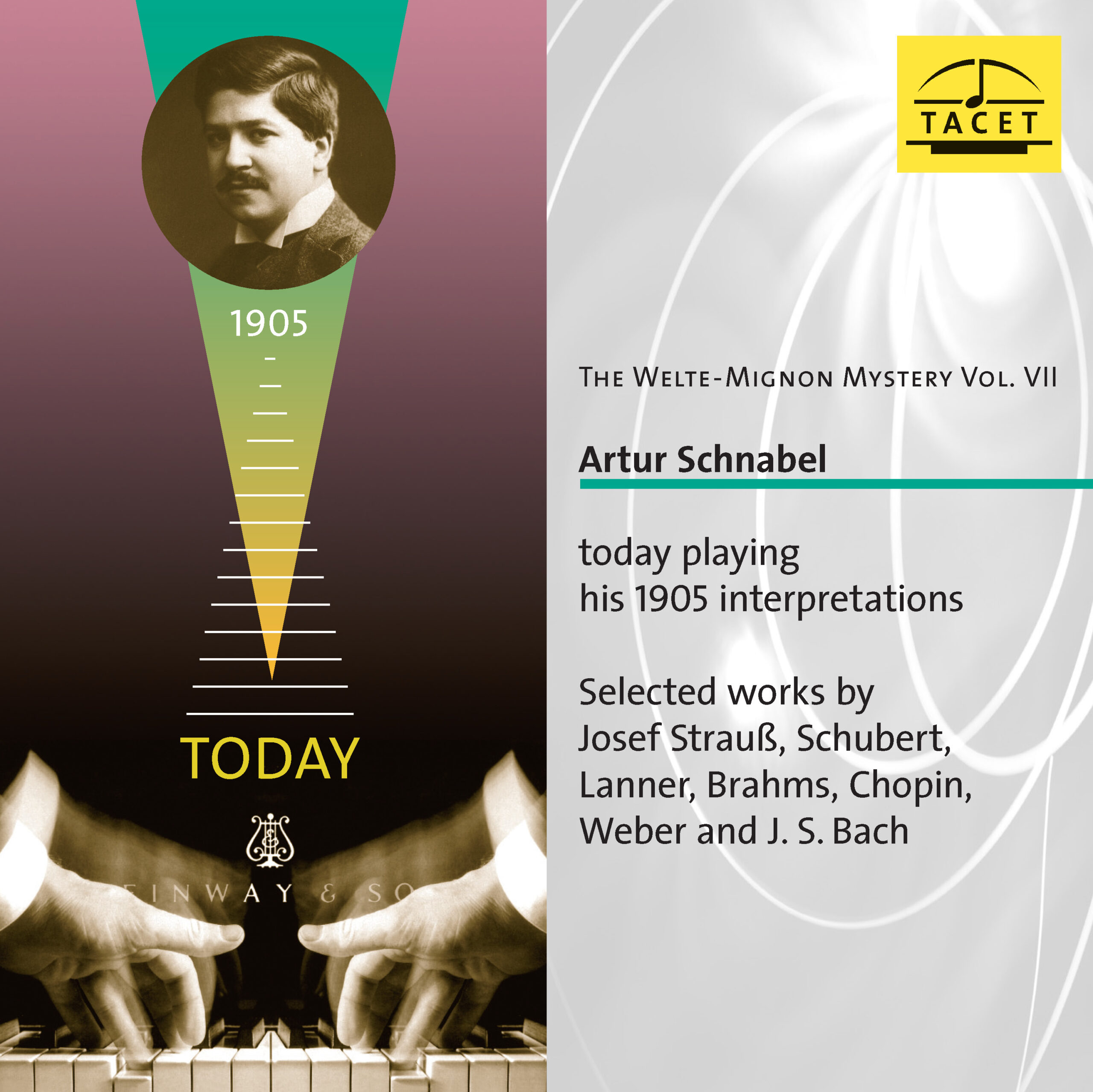

146 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. VII: Artur Schnabel

Description

This is not an historical recording. Yet mysteriously the music is performed in an interpretation which is historically authentic down to the last detail. The key to this mystery is: the original performer was present at the recent recording session, but not physically: the music is heard on a modern Steinway. Never has music stored in the Welte-Mignon system sounded so "right" or so well. Thanks to TACET′s much-praised recording technique, and because the Welte-Mignon memory system and sound production mechanism have now been newly adjusted for the first time by the leading expert in the field - and are thus able to meet TACET′s requirements. (Welte-Mignon was invented in 1904.) The Welte-Mignon mystery can now speak to us without distortion.

5 reviews for 146 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. VII: Artur Schnabel

You must be logged in to post a review.

Pianiste –

THE LESSONS OF THE PAST

The Magic of the Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… spielen ihre Werke.

Would you like to hear Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, and Reger playing their own works on a modern piano? And how about a "perfect" restoration of the interpretations by the early Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne, and Schnabel? The German label Tacet offers an anthology of rolls recorded by the Welte-Mignon system. The system is simple, but the process of reproduction is particularly complex! In fact, the pieces played by the composers themselves were digitized from the device invented in 1904 by the company Welte & Sons of Freiburg. The perforated rolls of the time captured the touch, pedal play, and the finest nuances. Today, all that is needed is to transfer these recordings onto a concert piano.

It is therefore a real shock to hear, in optimal listening comfort, Debussy’s Children's Corner and some Préludes, as well as Ravel’s Sonatine and Valses nobles et sentimentales, all played by the composers themselves. What lessons can we take away from this? First, the astonishing freedom with which these two geniuses approach their scores! It is also true that Ravel’s playing is not always flawless… But if we look beyond the purely technical aspect, we notice the extreme finesse and personalization of their touches. The dynamics are generally soft, with the fingers seeming to merely caress the keyboard. No brutality whatsoever. The clarity and gentleness are astounding. Other examples are equally striking, such as the two volumes dedicated to Brahms’ works interpreted by Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney, or Chopin’s Etudes played by Pachmann and Paderewski…

The virtuosity of these pianists is staggering, but even more surprising is the passion, the commitment, and sometimes even the coquettishness, the occasional unnecessary ornamentations that some perform almost as if they were tics. From all these master lessons, we learn that the strongest personalities only flourish after a visceral and profound understanding of the works. Schnabel in the waltzes of Josef Strauss and Josef Lanner (who would dare play this today?), Horowitz in 1926 in some Rachmaninoff Preludes, speak to us. Where does the charisma and charm of their interpretations come from? A mystery.

Every year, Tacet releases three or four new CDs from the Welte-Mignon archives. Worth collecting.

S. F.

_________________________________________________

Original Review in French language

LES LEÇONS DU PASSÉ

La magie des Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… jouent leurs œuvres.

Vous aimeriez entendre Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, Reger jouant sur un piano d’aujourd’hui leurs propres Oeuvres? Et que diriez-vous aussi d’une restitution « parfaite » des interprétations des premiers Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne et autres Schnabel? Le label allemand Tacet propose une anthologie des rouleaux gravés par le procédé Welte-Mignon. Le système est simple, mais le procédé de restitution particulièrement complexe! En effet, les pièces jouées par les compositeurs eux-mêmes ont été numérisées à partir de l’appareil inventé en 1904 par la firme Welte & Fils de Fribourg. Les rouleaux perforés de l’époque ont capté le toucher, le jeu des pédales et les nuances les plus fines. Il suffit aujour¬d’hui de transférer ces témoignages sur un piano de concert.

C’est donc un véritable choc que d’entendre dans un confort d’écoute optimal les Children’s Corner et quelques Préludes par Debussy, mais aussi la Sonatine, les Valses nobles et sentimentales de Ravel sous les doigts des compositeurs. Quelles leçons en retirons-nous? D’abord, l’étonnante liberté de ces deux génies vis-à-vis de leurs partitions! Il est vrai aussi que le jeu de Ravel n’est pas d’une justesse infaillible… Mais si l’on dépasse l’aspect purement technique, on s’aperçoit de l’extrême finesse et de la personnalisation des touchers. Les dynamiques sont généralement faibles, les doigts semblent effleurer le clavier. Sans aucune brutalité. La clarté et la douceur sont stupéfiantes. D’autres exemples sont frappants comme ces deux volumes consacrés à des œuvres de Brahms interprétées par Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney ou bien les Études de Chopin par Pachmann et Paderewski…

La virtuosité des pianistes est stupéfiante, mais on est plus surpris encore par la fougue, l’engagement, parfois même les coquetteries, les ornementations intempestives que certains provoquent comme des tics. De toutes ces leçons de maîtres, on retient que les personnalités les plus fortes ne s’épanouissent qu’après une compréhension viscérale et profonde des œuvres. Schnabel dans les Valses de Josef Strauss et de Josef Lanner (qui oserait jouer cela aujourd’hui ?), Horowitz en 1926 dans quelques Préludes de Rachmaninov nous interpellent. D’où proviennent le charisme et le charme insensés de leurs lectures? Mystère.

Chaque année, Tacet publie trois ou quatre nouveaux CD des archives Welte-Mignon. À thésauriser.

S. F.

Partituren –

The Welte-Mignon sounds from 1905, newly restored by Stuttgart sound engineer Andreas Spreer to emerge as if from a modern studio, cast a completely new light on the then just 23-year-old Artur Schnabel. More than twenty years before his first studio recordings, Schnabel—at the very beginning of his career—already plays with the discipline that would later become his hallmark: unpretentious, clearly structured, yet still pulsing with heartbeat and unsentimental simplicity. No lover of piano playing should miss these invaluable documents—if only for the dances by Lanner, Strauss, and Weber, which reveal an entirely new facet of Schnabel as a musician.

US

Audiophile Audition –

Schnabel’s Welte-Mignon Recordings: A Sonic Glimpse into Vienna’s Salon Culture

The patented process for the Welte-Mignon reproduction of keyboard playing might be construed either as a sophisticated gimmick or a kind of musical time-machine that allows us a glimpse into the musical past as transposed to a modern, brilliant-sounding Steinway. Artur Schnabel (1882-1951), the otherwise conservative exponent of the Leschetizky school of pianism, sat before the Vorsetzer mechanism in 1905, when for all intent, he was still committed to a more "romantic" ethos than his later, almost exclusively Viennese and German inscriptions permit.

The music of Johann Strauss and Joseph Lanner from Schnabel places him in the salon of virtuoso pianists from which he later would prefer to have been excluded. Harold C. Schonberg once designated Schnabel as "the man who invented Beethoven," an epithet meant to segregate Liszt and Chopin from Schnabel’s heady list of revered Vienna masters, Schubert, Brahms, and Beethoven. Schnabel called Chopin "the composer for right-handed geniuses."

So, this Tacet issue from the vaults of time proves most illuminating, as it places Schnabel into a circle of devotees of the Vienna waltz and Schubert evenings that could also embrace the "pretty" compositions of Chopin and Weber. Schubert’s noble waltzes flow effortlessly directly from the same fount as Lanner’s Old-Vienna Waltzes. The one Impromptu - the later recording of which for EMI remains a classic - has a brisker, risky element absent from the reading some 33 years later. The otherwise slight Intermezzo in C by Brahms gains anxious demonism in the course of its metric transitions, a real tour de force in a nutshell. Chopin’s F Minor enjoys an eccentric pulse without any break in the motoric regularity. Schnabel did commit to disc a later version of Weber’s charming Invitation to the Dance; here, the music proceeds both literally and tenderly, the accents suggestive of the rustic origins of the waltz form. The bravura passages ripple as briskly as anything from Hofmann, Brailowsky, and Arrau. Schnabel’s Bach always had an accent; in the Welte-Mignon incarnation, he sounds like Gould or Serkin.

The caveat about all this is in fact the loss of legato as a trait in Schnabel’s playing; more damning critics find all personality missing from the Welte-Mignon process. For Schnabel, whose touch identified him above all others, the mechanism may totally distort his keyboard persona: but to have this particular repertory, the Chopin Nocturne in F Minor, the second of the Schubert Klavierstuecke, the investment yields some fascinating results.

[Yes, though it was far superior to all the other piano-roll processes, the Welte-Mignon was not perfect, but would you rather listen to this music thru the roar of noise on 1905-vintage acoustic discs? (If there were any such.)...Ed.]

Gary Lemco

Pizzicato –

The marvelous Welte-Mignon rolls are available once again, offering a very comprehensive portrait of the pianist Artur Schnabel,

renowned both as a performer and as a teacher. The most striking feature of this collection of piano pieces is the sense of timing—the way the melodies unfold, the supple ease and freedom that permeate both Brahms and the Viennese waltzes.

A fluid and transparent technique characterizes these recordings, which include, alongside Chopin études, a transcription of Weber, a very free interpretation of Bach, and the irresistible waltzes of Josef Strauss…yet another remarkable historical document offered by the Tacet label.

itb

___________________________

Original Review in French language:

Les merveilleux rouleaux Welte-Mignon sont à nouveau disponibles, et voici un portrait très complet du pianiste Arthur Schnabel, qui était aussi renommé en tant qu′interprète qu′en tant que pédagogue. Le plus surprenant dans ce bouquet de pages pianistiques, c′est la notion de temps, la façon dont se déroulent les mélodies, l′aisance souple et la liberté qui imprègnent Brahms autant que les valses viennoises. Une technique fluide et limpide caractérise ces enregistrements, où l′on notera aux côtés d′études de Chopin la présence d′une transcription de Weber, une interprétation très libre de Bach et les valses irrésistibles de Josef Strauss…encore un document historique étonnant proposé par la compagnie Tacet.

itb

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

How It Really Sounded

Stuttgart sound engineer Andreas Spreer draws from the century-old Welte-Mignon rolls sounds that seem to come from a modern studio. This casts a completely new light on the then just 23-year-old Artur Schnabel in 1905. Everything that might normally bother listeners in historical recordings is wiped away, allowing us to fully immerse ourselves in the unpretentious, clearly structured, and manually brilliant playing of the great pianist.

Even here, Schnabel’s choice of consistently short pieces highlights not the virtuoso, but the musician. Schubert’s famous A-flat major Impromptu appears alongside the wonderfully idiosyncratic second of the late Piano Pieces, D. 946; Brahms’s delicately declaimed C major Intermezzo, Op. 119, sits beside petite works by Bach and Chopin. The austere G minor Nocturne by the adopted Frenchman, whom Schnabel did not particularly favor, is played with an almost rapturous strictness.

Carl Maria von Weber’s Aufforderung zum Tanz, rarely heard in the original piano version, as well as waltzes by Schubert, Lanner, and Josef Strauss, add a distinctive touch to the portrait of the young master. In their blend of unsentimental simplicity and pulsating heartbeat, these pieces are gems in Arthur Schnabel’s discographic legacy.

usc