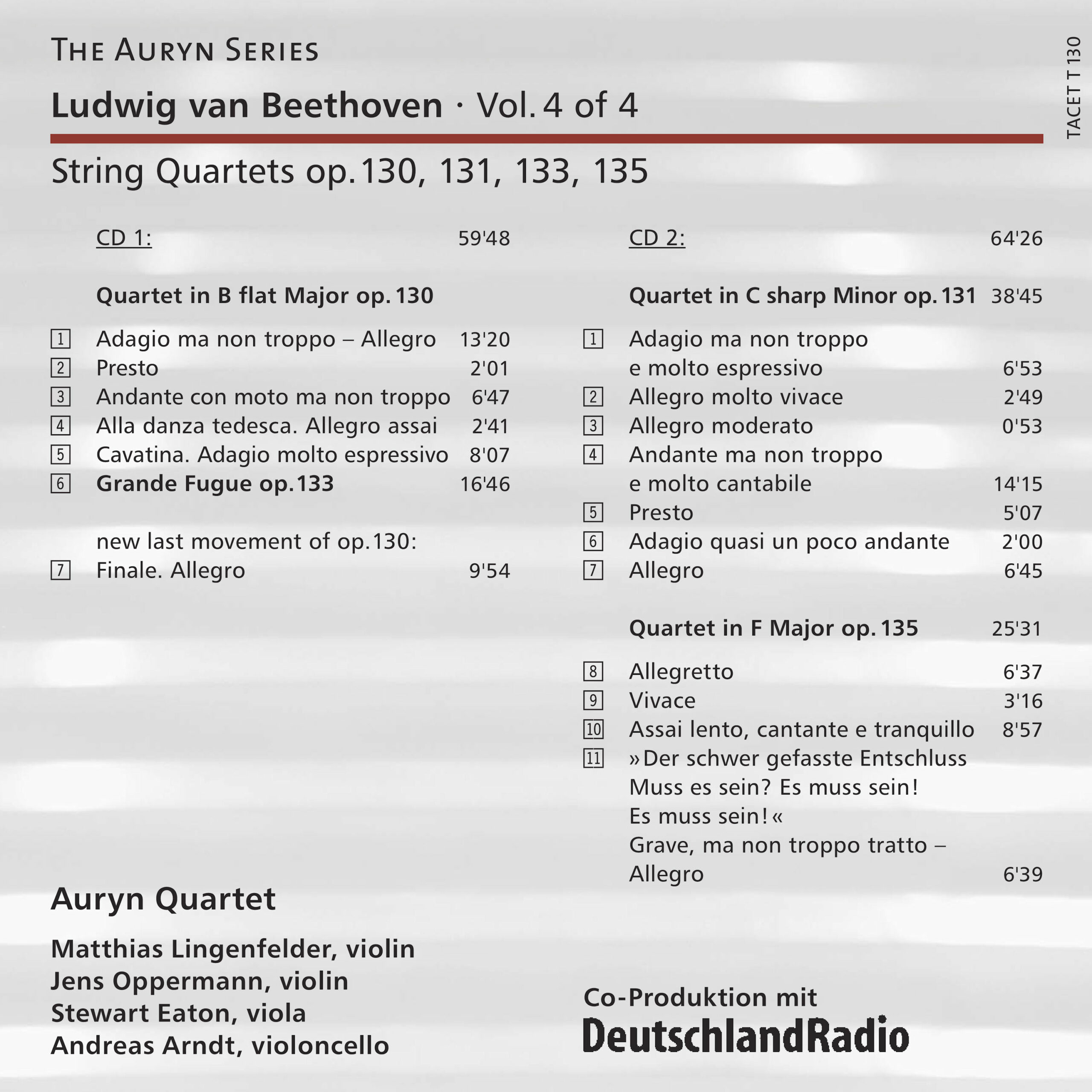

130 CD / L. v. Beethoven String Quartets ⋅ Vol. 4 of 4 op. 130, 131, 133, 135

Description

“With their expressive timbre and the technical excellence of the recording, the Auryn Quartet need not fear the competition, even though there is already a multitude of recordings in existence.” (Hartmut Lück, Klassik-heute)

There is no shortage of great and famous Beethoven Cycles, but there are no performances such as these. For me, this is now the set to beat. (Laurence Vittes)

13 reviews for 130 CD / L. v. Beethoven String Quartets ⋅ Vol. 4 of 4 op. 130, 131, 133, 135

You must be logged in to post a review.

Fanfare-Magazin –

Although the Auryn Quartet has been together for two decades, this release has provided my first exposure to the group. I trust it will not be my last. In every way these are distinguished readings. Recorded in 2002 and 2004, those of Nos. 14 and 16 are here, I believe, making their first appearance; those of No. 13 and the Grosse Fuga (the latter featured as the original finale—the later one following on a succeeding track) having been previously issued (Tacet 38). This release is tagged, "Volume 4 of 4," which evidently implies that the Auryn will be recording a cycle of Beethoven’s quartets. If this set is any indication, it should be a traversal that will hold its own with the best. Everything here commands one’s attention. Sonically, this is as realistic a reproduction of a string quartet as I have ever encountered. Closely miked, the resulting perspective puts the group smack in one’s listening room, with each musician clearly positioned. Yet no extraneous breathing is audible. Moreover, the dynamic range is uncommonly wide, impact in the loudest passages being especially forceful, the hush of the softest ones uncommonly clear, even when they are hardly more than a whisper.

Of course, this would all be for naught were the performances not so compelling. In the main, the Auryn’s pacing is middle of the road, sometimes a bit broader, other times a bit faster than that of other accounts by the Emerson, Talich, Cleveland, Vermeer, and Tokyo Quartets. But pacing is not the key issue here. The Auryn’s tempos always seem just, in good measure because of the group’s exceptionally clean playing, even in the most rapidly articulated passages. Then too, internal balances are carefully adjusted so that in sustained chords, for example, one can distinguish each voice. This is most welcome in the Grosse Fuga, where the clarity of polyphonic texture underscores how, in an almost spooky way, the music seems to foreshadow Bartók. Even when, on occasion, a tempo is somewhat unorthodox—the comparative fleetness of the fourth movement of No. 13 and breadth of the fourth movement of No. 14—the Auryn’s pacing sounds right. And nothing is ever pushed too hard, the finale of No. 14, for example, gaining impact by being a bit broader than in the admirable accounts of the Emerson and Tokyo Quartets. And although I prefer the Emerson’s somewhat fleeter account of the slow movement of No. 16, the greater breadth of Auryn’s certainly has merit. Indeed, in the Cavatina of No. 13, many may prefer the Auryn’s breadth to the faster pace of the Emersons. Especially impressive is the conversational clarity of the four voices in the opening fugue of No. 14. Exposition repeats are observed in the first movement of No. 13 and the finale of No. 16. Certainly for those who collect multiple versions of this repertoire or are plunging into it for the first time, this is a release well worth considering.

Mortimer H. Frank

Das Orchester –

--> original review

The two CDs with the string quartets op. 130, 131, 135 and the mighty Grosse Fuge op. 133 conclude the project Auryn’s Beethoven of the label TACET in co-production with DeutschlandRadio. Both the performers and the producers can be proud of this recording, for—to say it right at the outset—it is a trailblazing release that can confidently stand alongside the almost historical complete recordings by first-class ensembles such as the Amadeus Quartet, the Melos Quartet, or the Tokyo String Quartet.

For it is precisely the late string quartets—the two, op. 127 in E-flat major and op. 132 in A minor, not excluded—that are weighty milestones at which many a hopeful quartet has miserably failed. For while the first six string quartets op. 18 were still written in a “proper” manner, modeled on Haydn and Mozart, even Goethe’s well-known bon mot about the genre—that it seemed as if four reasonable people were having a conversation—no longer applies to Beethoven’s late quartets. Too profound, too complex, indeed too philosophical, and too far pointing into the future are the late quartets; for his contemporaries incomprehensible, who often rejected them as too bizarre, with some even ridiculously reproaching the composer that, influenced by deafness, he had forgotten how to compose, since parallel fifths and octaves appear.

What remains is the moving profundity, when one listens with great delight to the four musicians playing music that is gripping, and despite the complexity of the compositional lines and musical statements, appears fresh and engaging. Even the fugal Adagio—incidentally the only one in Beethoven’s oeuvre—in the C-sharp minor quartet does not come across as dragging, but as well thought out and exceedingly transparent, even if the Presto within the overall complex seems somewhat rushed. Speaking of fugue: the Grosse Fuge op. 133, at whose unbridled force and unusual scope of 741 measures even Beethoven’s biographer Walter Riezler recoiled—characterizing it, because of its eruptions, as uncanny, bold, and breathtaking, and noting that it reminded him of an organ fugue by Bach—is played truly masterfully by the Auryn Quartet. Precisely here the ensemble shows its flexibility in playing: in the unison “Ouvertura,” where the main theme is introduced with power; in the four fugue sections with their stark polarization and harsh contrasts; and then in the delicate pianissimo passages, which are drawn out lyrically, almost tenderly and lovingly. By contrast, the subsequent alternative final movement may seem almost pale. The other two string quartets are interpreted with similar consistency; here as well, the musical unity is preserved despite the seven movements, as is the retrospective modernity of the last string quartet, op. 135.

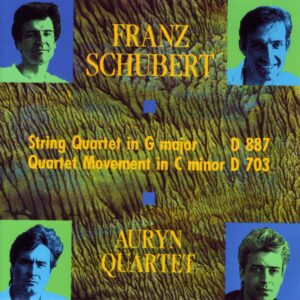

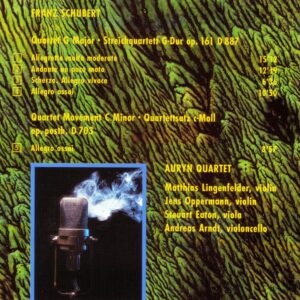

This recording is not only a gain and a must for the Beethoven connoisseur, but also for those who have not yet entered the world of “late Beethoven.” One can only hope that the Auryn Quartet with Matthias Lingenfelder, Jens Oppermann, Stewart Eaton, and Andreas Arndt will record many further works from the almost unmanageable quartet literature. A few milestones—Haydn, Schubert, Debussy, Ravel, Britten, Bialas—have already been set for eternity.

Werner Bodendorff

Dortmunder Zeitung –

Summit works offer views full of extremes

It is accomplished: with the final double CD just released on TACET, the Auryn Quartet has completed the cycle of all Beethoven string quartets and has scaled the summit of classical chamber music art—both technically and musically.

Contrasting is the 524-minute-long journey of the ensemble, based among other places in Dortmund. The series, partly already prize-winning, belongs to the most exciting complete recordings of Beethoven’s quartets. What already distinguished the first three double CDs characterizes especially this last one, which again impresses with excellent sound quality, transparent down to the smallest detail.

With their finely nuanced and sensitively modulated playing, the Auryns plunge deeply into a game full of extremes, always on the lookout for something new to discover between Beethoven’s notes, making audible his development into a radical setter of tones, who with his late works opened wide the door to late Romanticism. Out of a dark, sound-saturated string mist the Auryns in Opus 130 develop scenes of impulsive haunting, let the music dance, and lead it inevitably into the Grosse Fuge, which after Beethoven’s death appeared separately as op. 133.

The Auryns approach this fugue with courage: harsh, so that one often hears the wood of the instruments, compressed to the extreme and at the same time extremely well contoured. Far more “classical” sounds the new final movement to op. 130. It builds bridges to op. 131 in the unusual key of C-sharp minor, which traverses sound worlds of unheard dimensions—from vital dance movements through pallidly expressed world-weariness to the wild, expressive, contrast-rich ghost-dance finale. That the Auryn Quartet has played in the same formation for almost a quarter of a century may have benefited its dense, unified interpretation of Beethoven, especially in op. 135, which Wagner described as the “daily routine of a ghostly heathen.”

The orchestral visions of this swan song of the genre are made excellently audible by the four string players—from the melancholy morning devotion to the painful renunciation, an exceedingly intimate and warmhearted farewell song.

JG

Niedersächsische Allgemeine –

Beethoven Compelling

When in early August the Summer Music Days in Hitzacker offer a foray through the world of the string quartet, this ensemble can also be heard there several times: the Auryn Quartet, not quite as well-known as the handful of internationally celebrated top ensembles, but in any case one of the best of its kind. Last year, the Auryn Quartet recorded all of Ludwig van Beethoven’s quartets in such a compelling way that one could only marvel. Analytical clarity of mind here combines with a suggestive expressive power that does justice especially to the works of Beethoven’s middle and late creative periods. The Auryns never shy away from probing to the extremes the contrasts and ruptures composed by Beethoven. At the same time, they never lose sight of the overall architecture of the pieces and shape broad, highly intense arcs of tension that force even the most opposing emotions together within the smallest space. Especially the late quartets succeed so impressively that only the very highest comparisons—with the Kolisch or the Juilliard Quartet—can be invoked.

Reinald Hanke

Klassik heute –

With this installment, the Auryn Quartet has completed its recording series of all the string quartets by Ludwig van Beethoven (four installments, each with two CDs). This final installment contains those late quartets which, in their completely novel formal conception and also in their radical rejection of any merely entertaining sound ideal, point farthest into the future—the C-sharp minor quartet with its uninterrupted quasi-one-movement structure points directly ahead to Arnold Schoenberg’s First Quartet.

The Auryn Quartet meets this challenge with great seriousness and on a high technical level, but also with that courage to take risks which alone lends these works their immensely avant-garde impact. The four musicians offer a performance of breathtaking tension, but also of deep immersion into harmonic and structural details in which time itself seems to stand still. With this achievement, outstanding both in tonal-expressive terms and in recording technique, the Auryn Quartet need fear no competition, even in view of the multitude of already existing recordings.

The reviewer would like to make only two tiny remarks: on the one hand, one could imagine the clarification of the polyphonic density, for instance in the first movement of the B-flat major quartet, as somewhat more vividly realized; here, as also occasionally elsewhere, the overall sound seems more vertical-compact than horizontally “unfolded.” On the other hand, the coupling of the B-flat major quartet with the Grosse Fuge and thus the isolated addition of the new finale does not appear entirely coherent, for the Grosse Fuge, by Beethoven’s own decision, can also stand alone, whereas the newly composed finale cannot. But here the listener can make his or her personal decision by selecting tracks.

Hartmut Lück

Südkurier –

What the Auryn Quartet does with Beethoven’s string quartets is pretty striking. It plays a modern Beethoven, who shows rhythmic angularity just as much as intricate dynamic progressions. At the same time, it is by no means the case that the deep emotional dimension that Beethoven’s music always also contains—the wistful, the fragile, the humane and the heavenly—gets lost. On the contrary, Auryn’s Beethoven lives from the power of the opposition between cold and warm, between heaven and hell, which here is cultivated at the highest level. The recording can absolutely stand alongside the great ones (Melos, Berg).

des

hermann – das magazin aus cottbus –

(…) Now brought to its climax: pianissimi as subtly roughened marginal phenomena between hair and string, melodic arches that seem to span endlessly. Fantastic!

Maria C.

Fono Forum –

In the slow movements they achieve moments of profound, at times truly magical beauty: how the Auryns, for example, sing inwardly, as if with a muted voice, the heavenly Cavatina from the monumental Quartet op. 130, how they savor each change of note almost tenderly, and despite the very slow tempo are always able to span the arch over the greater whole—that is simply masterful. Equally enthralling is the Lento from the F-major Quartet op. 135, suffused with otherworldly melancholy and tinged with organ-like colors. (…).

Markus Stäbler

The best new recordings from North America –

In those concluding installments of their complete Beethoven cycle, the Auryn Quartet, who take their name from the amulet that grants intuition in Michael Ende′s fantasy, The Neverending Story, have put forth a breathtakingly new and illuminating proposition. Instead of presenting the music as late Beethoven, riddled with awkward enharmonic changes and thorny technical obstacles, they play them as mainstream classical music of great confidence and power. In so doing, they have rethought numerous commonly accepted interpretive solutions. A few examples will have to suffice. The way the Auryn embrace the composer′s idiosyncratic use of clockwork elements, like the triplets in bar 48 of the first movement of Op. 132, transforms notions of whet drives the Beethoven machine. And the overwhelming positive attitude with which they play the Meno mosso e moderato in the Grosse Fuge proves that a quartet can master this superhuman movement. There are also deaply profound individual touches, as when Matthias Lingenfelder′s tone breaks before the "Beklemmt" section of the Cavatina in Op. 130.

Beyond these moments of epiphany, the Auryns possess a sense of latent power that creates a superb kind of musical tension, a rare ability to phrase with a kind of radiant Italianate grace and in hypnotic big pictures arches, and to do so as with one voice. Unlike the Takáks, whose late quartets set has just been released on Decca, there is no sense that this is a first violinist and "the others", or that the music is a series of (occasionally dysfunctional) fragments, however brillantly or inimitably played. At times, the Auryn performances seem so close to what one sees unfolding on the printed score that it is possible to believe you are hearing directly what Beethoven had in mind. Perhaps only the Busch Quartet had this kind of liberating vision.

Working in the Cologne studio of DeutschlandRadio with two Neumann M49 microphones, Andreas Spreer has captured the Auryn in what sounds like one of those science fiction continuums where space stretches to fit time, the sound rich and detailed without being analytical, the lower strings of the viola and cello having a wonderful grainy quality to them. There is no shortage of great and famous Beethoven Cycles, but there are no performances such as these. For me, this is now the set to beat.

Laurence Vittes

Wiesbadener Anzeiger –

Auryn’s Beethoven: The Completion of the Cycle

We always pretend that we can imagine the feelings of a composer who helplessly has to watch his hearing deteriorate inexorably, irretrievably—and who does not know whether tomorrow everything might already be over. What fears, despair, certainly also pointless hopes, what anger and resignation alternated, probably in rapid succession, cannot even be guessed at, even if one knows the Heiligenstädter Testament and the surviving conversation books inside out.

The unanswerable question of what may have occurred between the barely audible and the complete silence of the outside world, of course, arises for every musician and ensemble who has been so reckless as to engage with Ludwig van Beethoven’s piano sonatas or string quartets. Suddenly, after the concentrated, classically measured Quartetto serioso op. 59, the classical world visibly unravels—and no one will ever be able to say how this sounded in the composer’s musical inner ear. One can, however, at least attempt to make the enormous rupture audible and to elevate the miniature moments, the immense Adagio movements, the mighty, entirely new fugues to regions where conventional notions of beauty are also audibly put to a severe test.

And precisely this is what the Auryn Quartet does in the conclusion of its complete Beethoven recording. The much-praised, sometimes described as “classical” polish of the previous recordings now, after having already been significantly challenged in Opus 95, actually reaches borderline territories, in which every parameter is, so to speak, pushed and bent to the extreme: pianissimi as subtly roughened marginal phenomena between hair and string, melodic arches that seem to span endlessly, then again tempi of such ghostly furioso as if dictated by demons—anyone who until today did not know what Beethoven cared about besides Schuppanzigh’s violin could learn it here. And those who already knew it encounter quite radical facets, light-years away from the classical beginning of the cycle, because at that point they were still in the stars.

Bayern 4 Klassik Radio, CD Tipp –

(…) Matthias Lingenfelder, Jens Oppermann, Stewart Eaton, and Andreas Arndt play the three great late quartets (…) brilliantly, technically flawless, yet in such a way that what puzzled Beethoven’s contemporaries—and continues to fascinate us to this day—remains unsmoothed: the dark, the bizarre, and the jagged. The great slow movements succeed wonderfully, doubtless the intellectual centers of the late quartets. And what Richard Wagner wrote about the final movement of the C-sharp minor Quartet op. 131 is made audible and tangible by the Auryn Quartet: “This is the dance of the world itself: wild delight, painful lament, rapture of love, supreme bliss, agony, frenzy, lust and sorrow; there it flashes like lightning, storm, rumble: and above it all, the immense player who forces and enchants everything…”

Oswald Beaujean

Crescendo –

The Auryn Quartet, arguably one of the finest German string quartets, has completed its complete recording of Beethoven’s string quartets!

The ensemble, which has been playing together in the same formation for over twenty years, possesses an extremely refined sound culture with perfect balance between the different instruments. The Auryns’ rich palette of tonal colors is brought out superbly thanks to the audiophile recording technique, making this series highly recommendable. Only those equipped for multichannel sound should wait a little longer: a multichannel version of the cycle has been announced!

KH/CMS

Welt am Sonntag –

Final Test of Maturity

It is accomplished: the Cologne-based Auryn Quartet has recorded all of Beethoven’s quartets.

No musician can avoid Beethoven. And certainly not a quartet. If someone were to write a history of the string quartet without mentioning Beethoven, it would be as if describing the development of humanity while leaving out the upright gait, the discovery of fire, or the invention of the wheel—or all of them at once. In this sense, it is no wonder that the four gentlemen of the Auryn Quartet sit so cheerfully together in Matthias Lingenfelder’s kitchen, sipping a milk coffee before rehearsal. Anyone who has recorded all of Beethoven’s string quartets has accomplished something fundamental and can therefore allow themselves to be relaxed.

These days, the fourth and final double CD of the Auryn Quartet’s Beethoven recordings has been released. One can breathe freely. A commitment has been fulfilled, an urgent concern addressed, a heartfelt wish realized—each of the four expresses the significance of these recordings a little differently. All four are happy: to record Beethoven’s quartets completely on CD—“that just had to happen now,” says first violinist Matthias Lingenfelder matter-of-factly.

On the other hand, there is, of course, the burden, the pressure: anyone who ventures into the public arena and the eternal sound archives with these quartets places themselves in a lineage, a tradition—and, consequently, also in comparison: with the Amadeus Quartet, the Guarneri Quartet, the LaSalle Quartet, the Melos Quartet, the Juilliard Quartet, the Alban Berg Quartet, and so on. Since the advent of modern recording technology, every major ensemble has left its interpretation of these sixteen works on disc. For a rising quartet, this can easily be intimidating. Why add yet another interpretation to the market? “I would have thought in the past,” says cellist Andreas Arndt, “that making a complete Beethoven recording—well, that’s nonsense.”

Today he thinks differently. Today, 28 years after Matthias Lingenfelder, Jens Oppermann, Stewart Eaton, and Andreas Arndt came together at the Cologne Conservatory to play in a quartet, this mammoth project seems to them inevitable, a natural next step in the life of their ensemble. In essence, this recording of Beethoven’s string quartets is the last proof to be given that this quartet has reached maturity. A test of maturity after 23 successful years—something that exists perhaps only in classical music. The proof is now being issued by the critics.

“Of course we are nervous now,” says Matthias Lingenfelder. Now that everything is done, no corrections are possible, and all that remains is to wait for reviews and sales figures. Over nine weeks, spread across two years, the four Auryn musicians spent recording. And this, although Lingenfelder does not like recording very much, because “I really need the audience,” as he says.

They played the slow introduction of the final movement from Opus 18/6 into the microphones countless times, exploring every possible way to execute those few suggested notes—only to finally have to commit to one version. Or the slow movement from Opus 95: Andreas Arndt still believes they play it too quickly on the recording. How could a musician not be nervous in such circumstances? Always aware, as Matthias Lingenfelder says, “that this was the last chance; and that we would never do this complete recording again.” “Never again”—has anyone ever expressed so beautifully that a recording is always also a farewell?

Yet too much pathos would probably do the matter injustice. For the truth is that such a major project could not be undertaken without the calm and composure that the Auryn musicians radiate even while sipping their milk coffee. They would have gone mad had they questioned and dissected every single note, as they did in their early days—back when they prepared Beethoven’s Opus 74 for their first competition. The result being that this piece has been “traumatically marked” ever since, as Lingenfelder says. Anyone wanting to interpret sixteen central quartets of music history en bloc must be confident in their style and interpretive approach. Or, as Andreas Arndt puts it: “We just do it the way we do it.”

This brings us to the question of the characteristics of these recordings. In general terms, one can say: the listener will search in vain for a strikingly new approach, for a dazzling effect. Instead, the will for beauty is omnipresent. Auryn’s Beethoven is spectacularly unspectacular. Congratulations.

Andreas Fasel