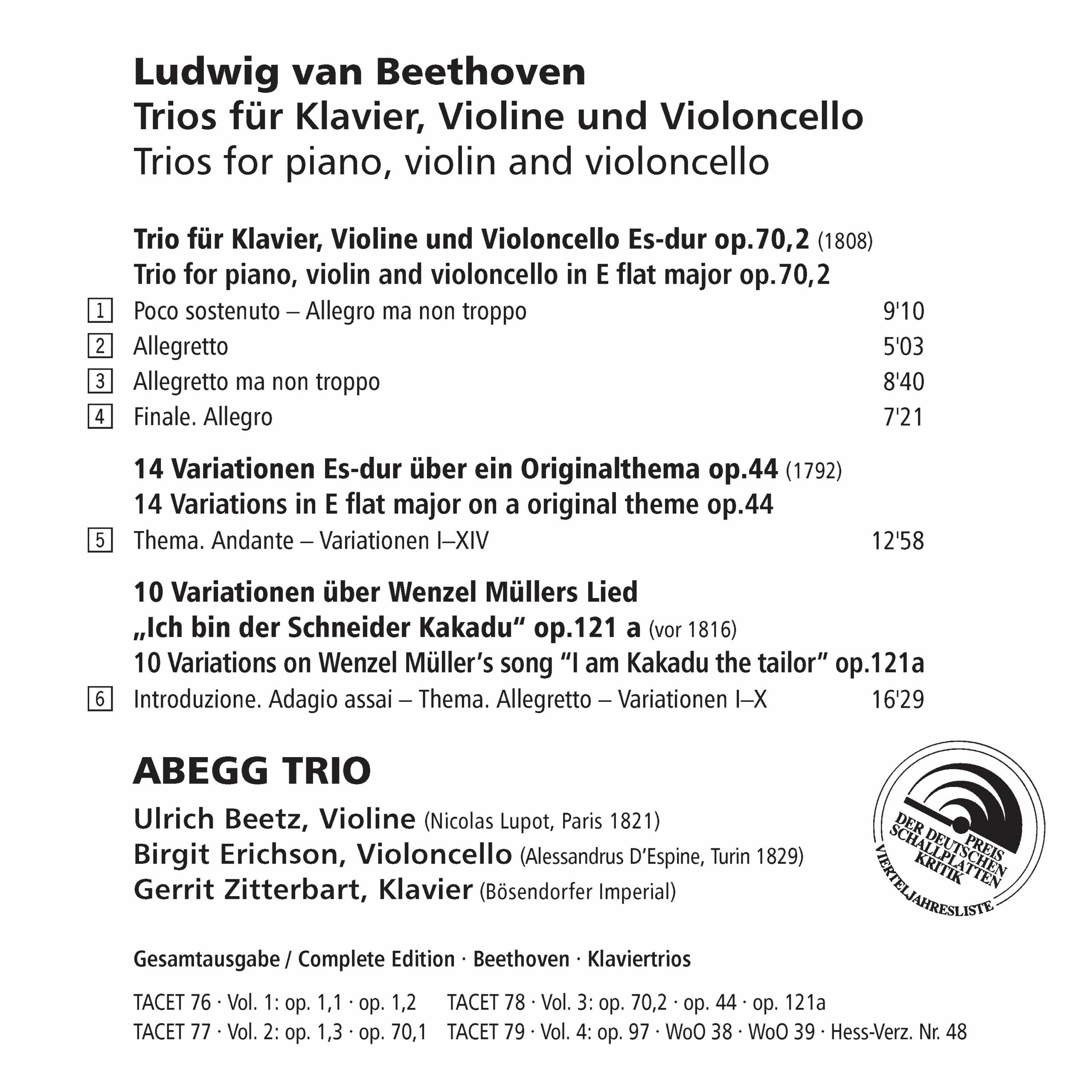

078 CD / Beethoven. Piano Trios Vol. III

Description

We awaited the third and fourth instalments of Beethoven’s Piano Trios by the Abegg Trio with eager anticipation. Now that they have been released, we can sum up as follows: our first impressions were right and our high expectations were confirmed; this trio, founded in Hanover in 1976, can rightly be called one of the great German piano trios. [...]" (Fono Forum)

4 reviews for 078 CD / Beethoven. Piano Trios Vol. III

You must be logged in to post a review.

CD-Führer Klassik –

Beethoven considered his first fully mature work to be the three piano trios, one of which is featured here—paired with the "Ghost" Trio, whose eerie middle movement inspired its name. The internationally underrated Abegg Trio has delivered what may be the most cohesive complete recording of all Beethoven trios, available on four individually obtainable CDs. Their interpretations are marked by powerful, vital playing that remains controlled, precise, and beautifully toned. The ensemble's sound is remarkably homogeneous, and the instrumental balance is excellent. The accompanying booklet's commentary is also exemplary.

Neue Musikzeitung –

Beethoven Tailor-Made

After endless debates about Beethoven’s original metronome markings—including the most absurd suggestions, such as halving the beat to make his supposedly excessive tempos more “playable”—it’s time to return to solid ground. The Abegg Trio does just that. Since Beethoven left no metronome markings for his piano trios, the ensemble turns to the most reliable witness: Carl Czerny (1791–1857). Czerny, as he himself wrote, “had enjoyed Beethoven’s piano instruction from a young age (beginning in 1801), studied all of his works as soon as they were published—many of them under the master’s direct guidance—and continued to benefit from Beethoven’s friendship and teachings until his final days.”

How fortunate that Czerny, in his 1842 treatise On the Proper Performance of All Beethoven’s Piano Works (Vienna), included not only the sonatas and concertos but also the chamber music for piano. Even more fortunate is that he didn’t stop at metronome markings but provided detailed descriptions of Beethoven’s compositional style and the manner in which his works should be interpreted. This is something we can—and should—follow. What remains puzzling is not just why this approach is so rarely put into practice, but why the entrenched habits of the concert hall seem to carry more weight than the clear, documented instructions of a Beethoven pupil. Could it be that the much-praised pursuit of historical authenticity has a blind spot here of all places? The Abegg Trio, founded in 1976 at the Hanover University of Music and Drama and now justifiably renowned internationally, doesn’t concern itself with the grumbling of chamber music enthusiasts wedded to tradition. Instead, it boldly puts Czerny’s well-founded guidance to the test.

Of course, this requires a certain level of skill. The freshness and vigorous momentum of the faster movements, played more swiftly and lively than usual, demand technical mastery, instrumental control, quick reflexes, and a cohesive yet relaxed ensemble dynamic. But when these conditions are met—as they are with the Abegg Trio—the rewards are immense. The first three trios, Opus 1 by a composer in his early twenties (with Czerny, as the facsimile in the booklet shows, already emphasizing the “more serious and grand character” of the third trio in C minor), benefit greatly from this departure from the stolid, bourgeois Beethoven conventions. Comparisons with recordings by even the most esteemed, concert-seasoned piano trios can be highly instructive. It’s not just the fluid tempos (which a few others occasionally achieve) but the gestural precision, the refusal to sacrifice attack, dynamic contour, or expressive presence that makes the difference: agility paired with refined phrasing, speed combined with intensity. And there’s something else remarkable: The Abegg Trio achieves what is exceedingly rare—a timbral unification between strings and piano by consciously emulating each other’s articulatory qualities. In simpler terms, they shorten bow strokes during rapid figuration while vocalizing the piano’s touch in melodic lines. The secret to their primary impression of seamless unity and musical coherence lies in these technical consequences of truly listening to one another.

One might suspect that what works so well for Opus 1, performed by a relatively young ensemble fully committed to chamber music, could prove less adequate for Beethoven’s later works. But the first two CDs of this set—soon to be completed with two more for a full cycle—dispel that notion with their rendition of the “Ghost” Trio. Not only do the Abeggs, unlike most others, fearlessly play the first movement with all repeats (without losing tension), but they also unfold the titular Largo assai ed espressivo as a vast, vivid scene—full of imagery and color, suffused with breathlike calm and pent-up excitement, from which the final Presto emerges into pulsating reality. Perhaps it was for the best that the Abegg Trio’s early 1980s recordings of the first two trios (for Harmonia Mundi) were not continued at the time. Now, with the benefit of grown experience, they are undertaking the complete cycle anew.

Ulrich Dibelius

Ekkehart Kroher –

There’s no need to sing further praises of Beethoven’s piano trios—their abundance of originality and unmistakable character speaks for itself. Instead, we should talk about the Abegg Trio, which has embarked on the adventure of recording the complete cycle and, in doing so, faces—and rises to—the challenge of formidable competition. From the very beginning, it’s clear with what care, seriousness, tonal culture, and depth of feeling Gerrit Zitterbart (piano), Ulrich Beetz (violin), and Birgit Erichson (cello) approach their task. Of course, their experience performing these trios on stage plays a role, but it alone doesn’t explain the impressive result. The Op. 1 trios, with which the young genius once introduced himself in Vienna, are not overburdened but presented as the unorthodox, uncompromising chamber music they are.

The Abegg Trio’s performance is impeccably clean, thoughtfully accented, and charged with tension. What’s particularly striking is their contemplative quality, which provides a compelling counterpoint to the music’s brilliance and bravura. This is especially true of the “Ghost” Trio, whose slow movement becomes not just the centerpiece but the true highlight. The espressivo of this music, richly differentiated in tone color, breathes organically in its surges and subsidences, lending the interpretation a vitality and tension that is palpable in every sense.

The imagination and contrast in the outer movements further reveal how deeply the Abeggs connect with Beethoven’s music. If their subsequent interpretations maintain this level, we can look forward to a first-rate complete

Ekkehart Kroher

Fono Forum –

The third and fourth installments of the Abegg Trio’s recordings of Beethoven’s piano trios have been eagerly anticipated. Now that they are here, we can conclude: The initial impressions (see FF 7/88) were not misleading—the high expectations have been met. Founded in Hanover in 1976, the ensemble has proven itself to be one of Germany’s great piano trios. Individuality, agility within cohesion, and independence under the demand for collectivity: The Abegg Trio breathes new life into worn-out interpretive ideals. Remarkably, they do so under the banner of “authenticity,” initially based solely on the observations of Carl Czerny, who documented them as a witness, student, and contemporary interpreter of Beethoven. But—and this is what defines the Abegg Trio’s stature—they aim for more than just fulfilling historical testimony. While they adhere to Czerny’s brisk tempos (an indirect confirmation of Beethoven’s metronome markings, which do not exist for these pieces) and use his further remarks as an irrefutable framework, the ensemble also employs partly daring means to achieve a closeness to Beethoven that becomes all the more convincing the more one compares it directly. Take, for example, the Beaux Arts Trio, whose beautifully toned playing reveals much while also concealing, and whose sense of polished refinement distracts from some boldness—boldness that has led Opus 70 No. 2 to be unfairly regarded as inferior to No. 1, the “Ghost” Trio. In fact, it’s high time this work was given a name of its own to elevate its status.

Manfred Karallus