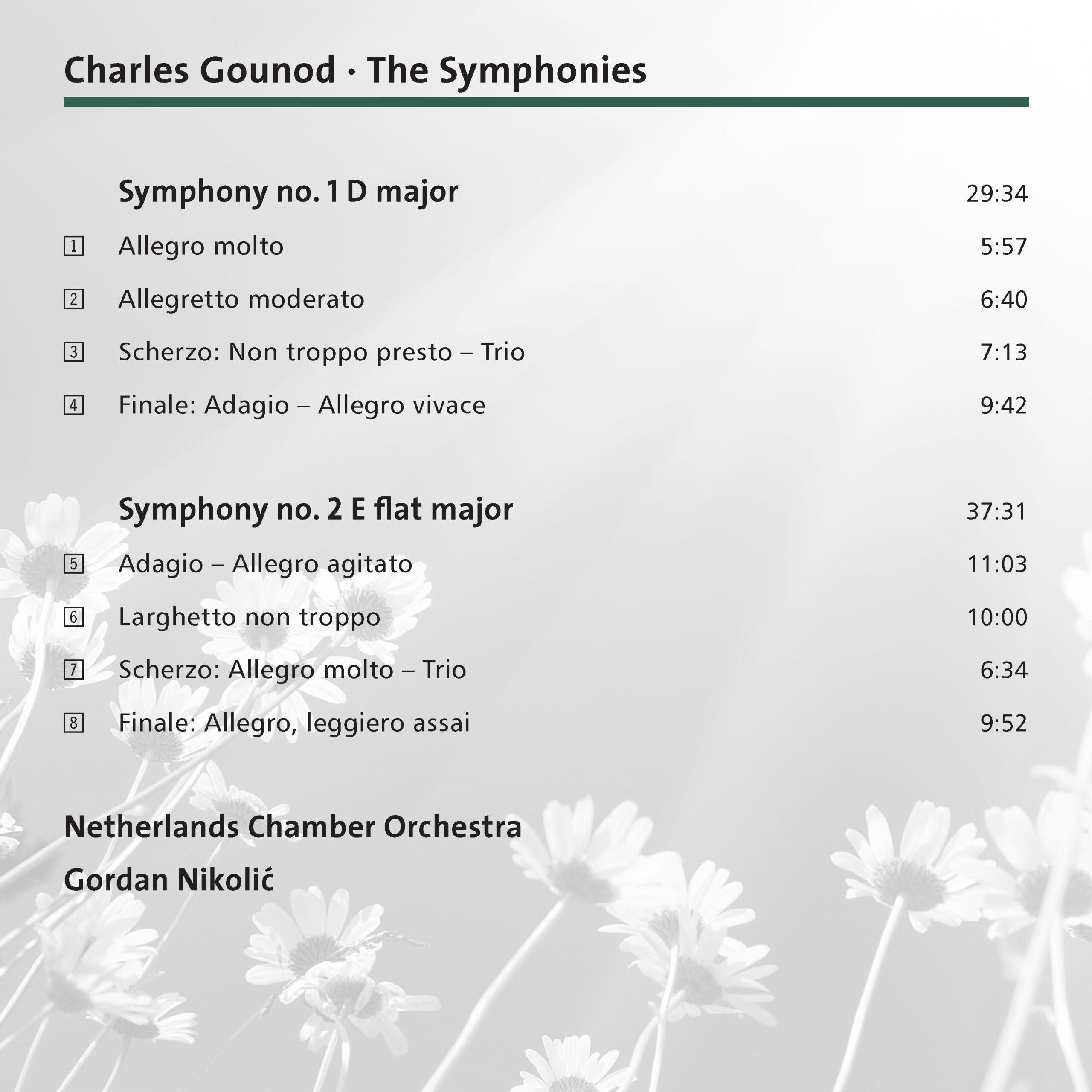

214 CD / Charles Gounod: Symphonies no. 1 & 2

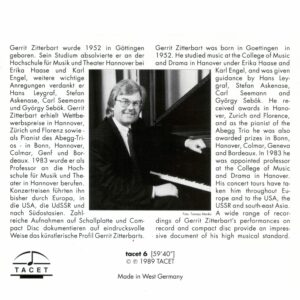

Description

Bang! A balloon bursts. Bang! A second one. And then a whole bunch of colourful melodies tumble from the Amsterdam Concertgebouw stage. The Netherlands Philharmonic Chamber Orchestra plays as boldly as little children in the street. The slow movement glows inwardly. The audience's hearts are filled with joy. Is that really Charles Gounod, the boring one who wrote that Ave Maria? Everyone listens spellbound to a cascade of rich ideas, artful instrumentation and the sheer joy of playing. They are amazed how, in the midst of all this, the violinist Gordan Nikolic manages to conjure up an atmosphere of simply letting it all happen, which doesn't demand anything of the listener and yet is completely compelling.

7 reviews for 214 CD / Charles Gounod: Symphonies no. 1 & 2

You must be logged in to post a review.

Fanfare Magazin –

--> original review

In the long-vanished heyday of High Fidelity magazine (or was it HiFi/Stereo Review?), one of the critics wondered aloud: "How was it that the man who was, at a guess, the 11th best French composer of his time parlayed a gift for sugary melody into one of the most popular operas ever written?" Although its vise-like grip on the world’s imagination has begun to loosen since the 1950s—though in terms of worldwide performances, it still figures firmly in Opera’s Top 40—Faust does have more than its share of apparently deathless tunes, something which cannot be said of its composer’s two symphonies.

Written during Gounod’s first flush of enthusiasm for the German symphony—sparked, in part, by his having met Fanny Mendelssohn during his time at the Villa Medici as a winner of the Prix de Rome—the Symphony No. 1 in D in an agreeable mélange of Haydn, Mozart, and Fanny’s brother Felix, with little that’s either original or particularly distinctive. Gounod’s pupil, the teenage Georges Bizet, was so fond of it that echoes can be heard in his early C-Major Symphony. (Bizet later famously disowned what was ultimately a far finer work lest he be accused of ripping off his teacher.) If the melodic inspiration in Gounod’s First Symphony is surprisingly thin, then it’s practically non-existent in the more tight-lipped and determined Second, which also rambles on much longer than it should, especially in the long-winded opening movement.

Collectors who own the classic Philips recording with Marriner and the Academy (462125) need not automatically trade it in, but as an unusually fresh-faced alternative, this new one is hard to beat. Along with nimbly responsive string section, the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra boasts a superb collection of principal winds, with the solo flute and oboe being particularly outstanding, interacting so well together that they almost give the lie to all the ancient cats-and-dogs/flutist-oboe player clichés. But then again, Julius Baker and Harold Gomberg, the New York Philharmonic’s peerless wind duo were not the best of friends. (Incidentally, it’s a myth that they hated each other. They didn’t. Just each other’s guts.)

As in the Marriner recording, Gordan Nicolic loses no opportunity to find the most endearing possible accent or the most delectable turn of phrase; unless they’re all world-class actors as well, the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra creates the unmistakable impression that they’re having the time of their lives, especially in D-Major Symphony, which crackles with wit, youthful exuberance, and life. The playing is also so brilliantly manicured that the applause at the end comes as a genuine shock. If the Second Symphony is less convincing—and Gounod was slightly taken aback by what he called its "certain degree of success"—then that’s undoubtedly the nature of the beast.

© 2015 Fanfare

Jim Svejda

The Infodad Team –

--> original review

(…) Die symphonische Produktion von Charles Gounod ist weitaus bescheidener und erfolgte in einer Umgebung, die sich deutlich von derjenigen von Schumann und Brahms unterschied. Schumanns letzte Symphonie, die Überarbeitung seiner originalen Zweiten, die wir als Nr. 4 kennen, stammt aus dem Jahr 1851, während Brahms‘ Erste erst 1876 erschien – obwohl der Komponist bereits 1855 daran arbeitete, im selben Jahr, in dem Gounod beide seiner Symphonien schrieb. Die Franzosen hatten zu dieser Zeit wenig Interesse an Symphonien, überließen die Führung in dieser Form den Deutschen und konzentrierten sich stattdessen auf die Oper. Es dauerte bis zur „Orgel“-Symphonie von Saint-Saëns (1886), dass eine französische Symphonie wieder die beeindruckenden Höhen von Berlioz‘ Symphonie fantastique (1830) erreichte. Es überrascht also nicht, dass Gounods Werke im Vergleich zu denen von Schumann und Brahms geringfügiger sind. Tatsächlich sind sie der Klassik stark verpflichtet, wie sie durch die Musik von Mendelssohn vermittelt wird – mit dem Ergebnis, dass sie besonders gut klingen, wenn sie von einem kleinen Ensemble, wie dem Netherlands Chamber Orchestra, aufgeführt werden. Gordan Nicolic, Konzertmeister des Orchesters und gleichzeitig Dirigent, trifft in einer neuen Aufnahme für Tacet genau die Flüchtigkeit und leichte Eleganz der Orchestrierung der Werke, und seine Live-Aufführung von Nr. 1 saust von Anfang bis Ende mit beträchtlichem Elan und einem sicheren Gespür für Gounods Stil – in seinen originalen und abgeleiteten Elementen. In Nr. 2, einer Studioaufnahme, ist Nicolic etwas zurückhaltender, obwohl er dem Komponisten im letzten Satz aufmerksam lauscht, den Gounod als Allegro, leggiero assai gekennzeichnet hat. Tatsächlich gibt es insgesamt eine Leichtigkeit in beiden von Gounods Symphonien – nicht eine, die auf einen Mangel an Ernsthaftigkeit hindeutet, sondern eine, die zeigt, dass Gounod Transparenz der Orchestrierung und leichte Zugänglichkeit musikalischer Ideen über himmelstürmende Intensität und stark dramatische thematische Entwicklung stellte. Diese Symphonien sind keineswegs die Hauptwerke, für die Gounod bekannt ist, aber sie sind ein wichtiger Teil seiner Produktion und werfen erhebliches Licht auf seine Herangehensweise an die Klarheit und Zugänglichkeit der Opernmusik. Sie zeigen auch, wie effektiv die symphonische Form sein kann, selbst wenn sie mit weniger Unwetter und struktureller Gelehrsamkeit verwaltet wird, als sie von den deutschsprachigen Komponisten in den Jahren nach dem Tod Beethovens erhalten hat.

Mark J. Estren, Ph.D., The Infodad Team

hifi & records 4/2015 –

Gounod's main work is often considered to be the Ave Maria, followed by Margarethe (alias Faust). His other operas, masses, and oratorios are mentioned in dictionaries but are scarcely found on CDs. These symphonies from 1855 are also rarities. Oleg Caetani recently presented both works with lightness and verve (cpo). Nikolic, known as a violinist-conductor since his Pentatone recordings, interprets them with a sense of internalization, almost profundity. Gounod was also the director of the Orpheon Grand Chorus in Paris, where the focus was on shaping vocal harmonies. The melodic character may have inspired Bizet, Gounod's student, for his Symphony in C major, composed a year later. There are cross-references, such as the secondary theme in the first or the cantilena in the second movement. However, Bizet had the ability to create tension arcs, while with Gounod, one must concentrate as his mood often changes, and motifs influenced by unexpected predecessors, such as Beethoven's Ninth, Mendelssohn, or Haydn, pass by. Nikolic unfolds the slow movements mysteriously from pianissimo and excels in the chamber music-like delineation of his committed orchestra. The recording features a spatially appealing, deep-staged sound. Worth listening to!

Ludwig Flich, hifi & records

klassik.com –

Sparkling charm

--> Review by Florian Schreiner (in German)

www.kultur-port.de –

--> original review

The Netherlands Chamber Orchestra, conducted by Gordan Nikolic, has recorded the two almost forgotten symphonies of the French composer Charles Gounod. In the recording, it is easy to hear the developmental lines of his music, which range from Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven to Felix Mendelssohn. He became acquainted with this music through Mendelssohn's sister, Fanny Hensel, during a study stay in Rome.

Da schreibt sich einer die Finger wund – Oratorien, zwölf Opern, Schauspielmusiken, Messen en masse, Märsche und Streichquartette. Und durch was wird man weltberühmt? Durch eine einzige, leicht schmalzige Melodie, die man über ein Präludium des längst verblichenen Johann Sebastian Bach gelegt hat. „Méditation sur le premier prélude de Bach“ hat der Franzose Charles Gounod (1818 bis 1893) seinen Welt-Hit genannt, in dem Bachs C-Dur-Präludium aus dem ersten Band des „Wohltemperierten Klaviers“ als Begleitung klimpert. Gounods zweitmeist gespieltes Werk dürfte übrigens „Inno e Marcia Pontificale“ sein, seit 1950 die offizielle die Papsthymne des Vatikan.

Von Gounods Opern sind „Faust“, in Deutschland gern unter dem Titel „Margarethe“ auf dem Spielplan, und „Romeo et Juliette“ dem Vergessen entkommen. Dass Gounod sich auch auf dem Gebiet der Sinfonie wacker geschlagen hat, ist dagegen eher eine Fußnote der Musikgeschichte geblieben. 1855 hatte er sich schon als Kirchenkapellmeister versucht, hatte seine ersten beiden erfolglosen Opern hinter sich, leitete den größten Männerchor der französischen Hauptstadt. Und beschloss, Sinfonien zu schreiben.

Im damaligen Frankreich ein mutiger Entschluss, das Musikleben in Paris war weitgehend auf die Oper fixiert, wenn man Sinfonien spielte, dann waren das die großen und bekannten Werke von Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven und Felix Mendelssohn. Sinfonien französischer Komponisten galten wenig, im Booklet der vorliegenden Aufnahme wird Camille Saint-Saëns zitiert, der 1880 schrieb: „Ein französischer Komponist, der die Kühnheit hatte, sich auf das Gebiet der der Instrumentalmusik zu wagen, besaß kein anderes Mittel, als dass er selbst ein Konzert gab und Freunde und die Kritik dazu einlud. An das eigentliche Publikum war nicht zu denken; der Name eines französischen Komponisten, noch dazu eines lebendigen, genügte, um alle Welt zu verscheuchen.“

Gounod's symphonic output was indeed limited to the year 1855, resulting in a two-and-a-half symphony that is not part of the core orchestral repertoire. The current revival by the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra under its concertmaster Gordan Nikolic is all the more commendable. It is worthwhile to listen to the two complete works that Gounod composed at the age of 37.

Die erste in D-Dur knüpft im Duktus an die späten Mozart und Haydn-Sinfonien an und schlägt auch eine Verbindung zu Schumanns sinfonischen Anfängen, abgeklärt heiter im Ton, von großer Eleganz und geprägt von Gounods Sinn für eingängige Melodik. Der zweite Satz, „Allegretto moderato“, erinnert an Beethovens Siebente und bedient sich wie er einer langen altertümlich fugierten, kontrapunktisch gesetzten Passage. Das Scherzo kommt hübsch brav daher, eher noch ein Menuett, und im vierten Satz folgt auf eine Adagio-Einleitung ein Allegro vivace, das freundliches Licht elegant tanzen lässt, als hätte Gounod Felix Mendelssohn über die Schulter geschaut.

Das ist kein Zufall. 1839 war Gounod Stipendiat des Prix de Rome. Während seiner römischen Jahre traf er die dreizehn Jahre ältere Fanny Hensel, verheiratete Schwester von Felix Mendelssohn. Er schmachtete sie zu deren Amüsement heftig an, und er lernte von der gestandenen Komponistin und virtuosen Pianistin viel über die deutsche Instrumentalmusik und die Werke Beethovens. Auf der Rückreise über Wien und Berlin machte er in Leipzig Station, wo er Mendelssohn traf und dessen dritte Sinfonie, die „Schottische“ hören konnte. So kam er als Kenner deutscher Musiktradition nach Paris zurück.

Gounod's second symphony in E-flat major already begins to emancipate itself from close adherence to models. Even though a little bit of Beethoven still shines through in the first movement, and the Scherzo also recalls the formal, thematic, and instrumental boldness of this master—there is a unique tone in the work, primarily expressed in a pronounced sense of lyrical melodies.

Das Nederlands Kamerorkest, Bruder des Nederlands Philharmonisch Orkest, ist mit seinen Konzerten im Royal Concertgebouw zuhause, wo auch die Live-Aufnahme der 1. Sinfonie entstand, was man dank der exzellenten Aufnahmetechnik kaum wahrnimmt – man ist richtig überrascht, wenn am Ende der Applaus aufbrandet. Außerdem ist es ständiges Ensemble der holländischen Nationaloper. Es nimmt sich der beiden Partituren von Gounod mit wunderbarer schimmernder Leichtigkeit und federnder Energie an. Vielleicht hätten die beiden Sinfonien genau so gespielt werden müssen, dann hätte Gounod über deren Erfolg besseres schreiben können als dass die erste von Publikum und Kritik „günstig aufgenommen“ wurde und die zweite sich „eines gewissen Erfolges“ erfreuen konnte. Vielleicht hat er da aber auch ein bisschen untertrieben – denn in den Jahren nach der Uraufführung wurde das sinfonische Doppelpack immerhin noch elf Mal in Paris aufgeführt. Da schrieb Gounod schon an der Oper, die sein größter Bühnenerfolg werden sollte: 1859 wurde „Faust“ an der Opéra national de Paris uraufgeführt – zwei Jahre, bevor dort Wagner mit der französischen Fassung seines „Tannhäuser“ grandios unterging. Gounods dritte Sinfonie blieb unvollendet.

Hans-Juergen Fink

Klassik heute –

--> original review

Von der kurzen Einlage einer Solobronchistin abgesehen gibt es keine vernehmlichen Hinweise darauf, dass Charles Gounods erste Symphonie für die gegenwärtige Veröffentlichung live mitgeschnitten wurde: Der Klang ist exzellent, die Spielfreude außerordentlich, das Timing der einzelnen Sätze und ihrer Relationen zueinander vorzüglich – und wenn endlich der Beifall losbricht, bin ich längst so sehr in den Bann der Ereignisse hineingezogen, dass ich ein nachdrückliches „Jawoll!“ nicht zurückhalten kann.

Of course, Gounod's attempt in early Schubert and mid-Beethoven is more entertainment than confession, but, dear heavens, what a delight this magnificent performance by the Netherlands Chamber Orchestra provides, which then, under Gordan Nikoli, also creates an exhilarating figure in the second symphony of the Frenchman.

This studio production possibly benefits even more from the fine transparency of the ensemble, among whose soloistic virtues an unfortunately unnamed bassoonist excels. With his downright enchanting cantabile and cheeky interjections, he becomes the secret star of this recording, without pushing himself forward or drawing the spotlight to himself. The naturalness of the compositional, conducting, and recording direction simply grants him the appropriate ambience to let his double reed sing with an eloquence that seems to long for the relevant passages from Beethoven's exemplary symphonies. Since no one attempts to inflate the music through exaggerated force, the interpretative conclusion can only be the highest rating.

Rasmus van Rijn

Pizzicato –

--> original review

Leicht und rhetorisch zugleich

France is not a land of symphonies, and the few examples do not belong to the treasury of literature. Nevertheless, it would be wrong to dismiss Charles Gounod's Symphonies No. 1 and 2 because of their uncomplicated character and simple language. Certainly, Gounod does not manifest himself as an ideasmith or a soul acrobat in these classically beautiful works. Yet, he freely weaves an imaginatively patterned musical tapestry. And precisely because the musical language is simple, one must listen carefully. The limitation of external means compels us to do so, as only then does the value of the symphonies reveal itself.

Gordan Nikolic takes the two symphonies at a considerably slower pace than his colleague Oleg Catani (for cpo) (see review here), and what ends in carefree music for the Italian takes on more meaning and more drama for Nikolic. His Allegretto moderato is truly restrained and possesses a different eloquence than Catani's because it brings more tension and more mystery into play. The movement is a small wonder of dynamic, agogic, and color nuancing. The finale is not only lively but also very well intensified. In the second symphony as well, the conductor lets things take their natural course, savoring the music delicately, shaping it lovingly, and ensuring that it constantly flows rhetorically. Nikolic comes closer in this approach to Patrick Gallois, who recorded the two works for Naxos.

The recording is spacious and simultaneously very present, well-balanced.

Remy Franck