Um Ihnen ein optimales Erlebnis zu bieten, verwenden wir Technologien wie Cookies, um Geräteinformationen zu speichern und/oder darauf zuzugreifen. Wenn Sie diesen Technologien zustimmen, können wir Daten wie das Surfverhalten oder eindeutige IDs auf dieser Website verarbeiten. Wenn Sie Ihre Einwillligung nicht erteilen oder zurückziehen, können bestimmte Merkmale und Funktionen beeinträchtigt werden.

Die technische Speicherung oder der Zugang ist unbedingt erforderlich für den rechtmäßigen Zweck, die Nutzung eines bestimmten Dienstes zu ermöglichen, der vom Teilnehmer oder Nutzer ausdrücklich gewünscht wird, oder für den alleinigen Zweck, die Übertragung einer Nachricht über ein elektronisches Kommunikationsnetz durchzuführen.

Die technische Speicherung oder der Zugriff ist für den rechtmäßigen Zweck der Speicherung von Präferenzen erforderlich, die nicht vom Abonnenten oder Benutzer angefordert wurden.

Die technische Speicherung oder der Zugriff, der ausschließlich zu statistischen Zwecken erfolgt.

Die technische Speicherung oder der Zugriff, der ausschließlich zu anonymen statistischen Zwecken verwendet wird. Ohne eine Vorladung, die freiwillige Zustimmung deines Internetdienstanbieters oder zusätzliche Aufzeichnungen von Dritten können die zu diesem Zweck gespeicherten oder abgerufenen Informationen allein in der Regel nicht dazu verwendet werden, dich zu identifizieren.

Die technische Speicherung oder der Zugriff ist erforderlich, um Nutzerprofile zu erstellen, um Werbung zu versenden oder um den Nutzer auf einer Website oder über mehrere Websites hinweg zu ähnlichen Marketingzwecken zu verfolgen.

Pianiste –

LESSONS FROM THE PAST

The Magic of the Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados … perform their own works.

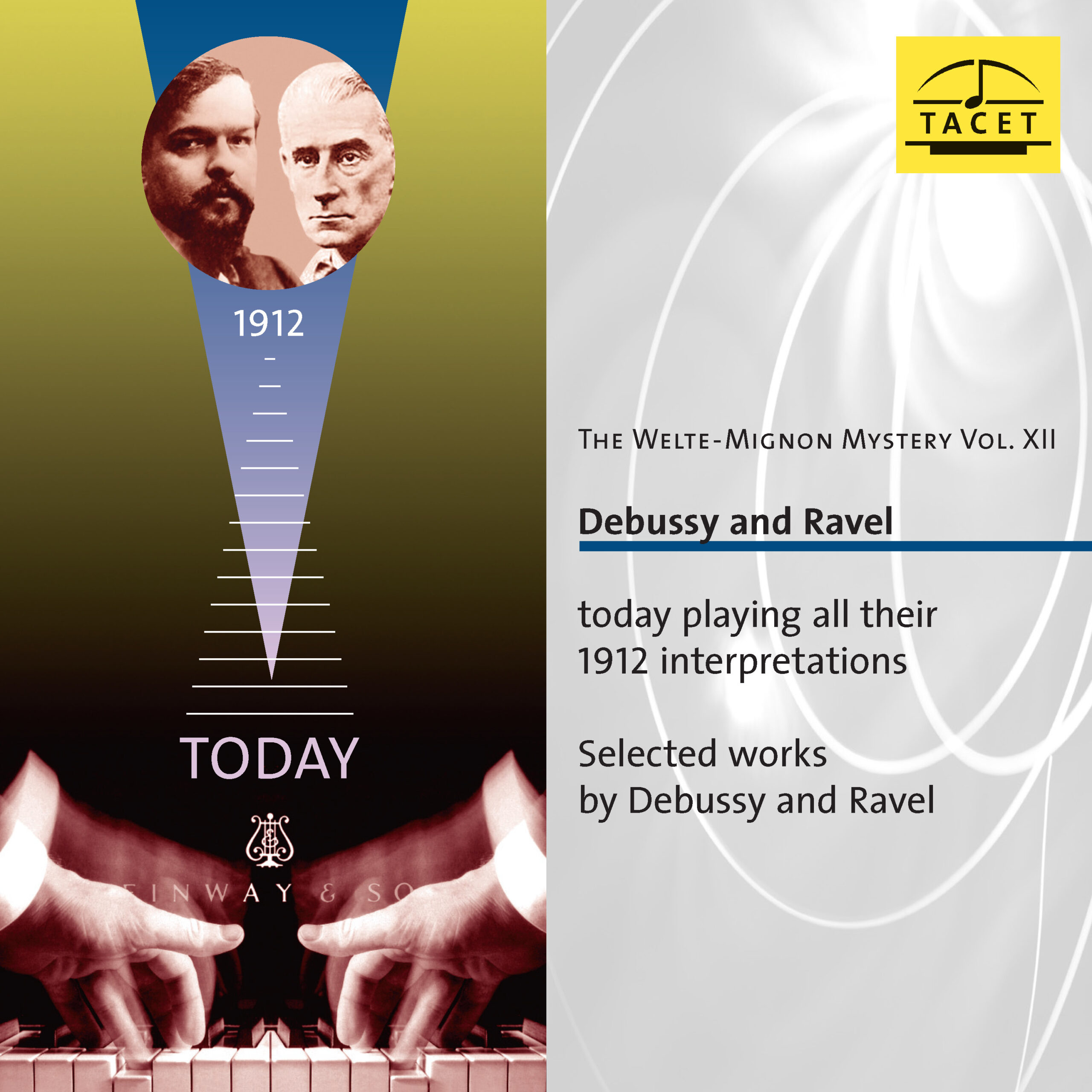

Would you like to hear Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, and Reger playing their own works on a modern piano? And how about a "perfect" restoration of the interpretations by the early Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne, and Schnabel? The German label Tacet offers an anthology of rolls recorded by the Welte-Mignon system. The system is simple, but the process of reproduction is particularly complex! In fact, the pieces played by the composers themselves were digitized from the device invented in 1904 by the company Welte & Sons of Freiburg. The perforated rolls of the time captured the touch, pedal play, and the finest nuances. Today, all that is needed is to transfer these recordings onto a concert piano.

It is therefore a real shock to hear, in optimal listening comfort, Debussy’s Children's Corner and some Préludes, as well as Ravel’s Sonatine and Valses nobles et sentimentales, all played by the composers themselves. What lessons can we take away from this? First, the astonishing freedom with which these two geniuses approach their scores! It is also true that Ravel’s playing is not always flawless… But if we look beyond the purely technical aspect, we notice the extreme finesse and personalization of their touches. The dynamics are generally soft, with the fingers seeming to merely caress the keyboard. No brutality whatsoever. The clarity and gentleness are astounding. Other examples are equally striking, such as the two volumes dedicated to Brahms’ works interpreted by Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney, or Chopin’s Etudes played by Pachmann and Paderewski…

The virtuosity of these pianists is staggering, but even more surprising is the passion, the commitment, and sometimes even the coquettishness, the occasional unnecessary ornamentations that some perform almost as if they were tics. From all these master lessons, we learn that the strongest personalities only flourish after a visceral and profound understanding of the works. Schnabel in the waltzes of Josef Strauss and Josef Lanner (who would dare play this today?), Horowitz in 1926 in some Rachmaninoff Preludes, speak to us. Where does the charisma and charm of their interpretations come from? A mystery.

Every year, Tacet releases three or four new CDs from the Welte-Mignon archives. Worth collecting.

S. F.

_____________________________________________

Original Review in French language

LES LEÇONS DU PASSÉ

La magie des Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… jouent leurs œuvres.

Vous aimeriez entendre Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, Reger jouant sur un piano d’aujourd’hui leurs propres Oeuvres? Et que diriez-vous aussi d’une restitution « parfaite » des interprétations des premiers Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne et autres Schnabel? Le label allemand Tacet propose une anthologie des rouleaux gravés par le procédé Welte-Mignon. Le système est simple, mais le procédé de restitution particulièrement complexe! En effet, les pièces jouées par les compositeurs eux-mêmes ont été numérisées à partir de l’appareil inventé en 1904 par la firme Welte & Fils de Fribourg. Les rouleaux perforés de l’époque ont capté le toucher, le jeu des pédales et les nuances les plus fines. Il suffit aujour¬d’hui de transférer ces témoignages sur un piano de concert.

C’est donc un véritable choc que d’entendre dans un confort d’écoute optimal les Children’s Corner et quelques Préludes par Debussy, mais aussi la Sonatine, les Valses nobles et sentimentales de Ravel sous les doigts des compositeurs. Quelles leçons en retirons-nous? D’abord, l’étonnante liberté de ces deux génies vis-à-vis de leurs partitions! Il est vrai aussi que le jeu de Ravel n’est pas d’une justesse infaillible… Mais si l’on dépasse l’aspect purement technique, on s’aperçoit de l’extrême finesse et de la personnalisation des touchers. Les dynamiques sont généralement faibles, les doigts semblent effleurer le clavier. Sans aucune brutalité. La clarté et la douceur sont stupéfiantes. D’autres exemples sont frappants comme ces deux volumes consacrés à des œuvres de Brahms interprétées par Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney ou bien les Études de Chopin par Pachmann et Paderewski…

La virtuosité des pianistes est stupéfiante, mais on est plus surpris encore par la fougue, l’engagement, parfois même les coquetteries, les ornementations intempestives que certains provoquent comme des tics. De toutes ces leçons de maîtres, on retient que les personnalités les plus fortes ne s’épanouissent qu’après une compréhension viscérale et profonde des œuvres. Schnabel dans les Valses de Josef Strauss et de Josef Lanner (qui oserait jouer cela aujourd’hui ?), Horowitz en 1926 dans quelques Préludes de Rachmaninov nous interpellent. D’où proviennent le charisme et le charme insensés de leurs lectures? Mystère.

Chaque année, Tacet publie trois ou quatre nouveaux CD des archives Welte-Mignon. À thésauriser.

S. F.

Pizzicato –

"What a moving pleasure to hear Debussy and Ravel play their own works in the best sound quality. The 1912 Welte-Mignon piano rolls make it possible! We have already underlined the quality of the TACET Welte-Mignon recordings on other CDs in this series, and there are no compromises to be made this time either: There are no better Welte-Mignon recordings on the market than this one." (Pizzicato)

Debussy surprises in his works with a rather brisk, fluid, yet dynamically finely nuanced style of playing that is remarkably ‘sober’. There are undoubtedly many better Debussy interpreters than the composer himself. Ravel’s playing, however, sounds even more sober—dare one say, bland—and his technical quality is another matter entirely. With a Sonatine performed as it is here, any conservatory student today would fail. Yet this only makes the document all the more fascinating, quite the opposite!

RéF

Klassik heute –

This is not an historical recording. Yet mysteriously the music is performed in an inter- pretation which is historically authentic down to the last detail. The key to this mystery is: the original performer was present at the recent recording session, but not physically.

This may be poorly phrased, but it is not incorrect in substance: Tacet has re-played and recorded Welte-Mignon rolls by Debussy and Ravel, assisted by “the finest expert,” Hans-W. Schmitz. In his liner notes, Schmitz meticulously demonstrates the (hitherto largely unappreciated) sonic refinements of which the Welte mechanism was already capable in 1912—and the challenges that today’s Welte exponents must confront: “Adjustments must be made that significantly improve the control of strike dynamics and playback tempo. This has long been overlooked due to lack of knowledge.” Schmitz, of course, does not fail to point out the limitations of the Welte rolls: “Evidently, for market-economic reasons, the company Welte accepted a marginal restriction in the playback apparatus: it does not regulate the volume of each individual note, but only separately for the bass and treble sides. Dynamic differentiation of simultaneously struck notes within chords […] is therefore impossible.” Whether Debussy and Ravel—neither of whom were concert pianists—would have been capable of making many such differentiations is another question.

The results are certainly impressive to hear. In terms of line flexibility, coloristic variety, and plasticity, Welte rolls presented in this way hardly fall short of modern recordings. Schmitz’s achievements prove particularly advantageous in the ‘impressionist’ repertoire. While one might be willing to forgo sonic subtleties in the ‘German’ or ‘Austrian’ repertoire—Bach, Beethoven, Mozart—such subtleties are the very ‘substance’ of Debussy and Ravel. In this light, Schmitz’s new editions must be considered a genuine sensation: We hear Children’s Corner or the Préludes, and from Ravel, the Sonatine in F minor or Valses nobles et sentimentales—or at least their composers—as if for the very first time.

As for the stylistic gestures of Debussy and Ravel, a certain nonchalance, even casualness, can be observed. It seems that neither was fully aware of the eternal significance of their recordings. This is evident, on the one hand, in technical inconsistencies and, on the other, in a rubato freedom and a genius-like, improvisational spontaneity that seems quite alien to us—trained as we are in the crystalline rigor of a Benedetti Michelangeli—yet it bears the mark of ‘authenticity.’ The rolls reveal just how deeply, especially in Debussy’s case, the 19th century still held sway.

Despite all this: While this record may be historically highly revealing, above all, it is a musical delight.

Dr. Daniel Krause

MDR, Take 5 –

At a time when recording music still seemed nearly impossible—at the beginning of the 20th century—a sensational method was developed: using perforated paper strips on piano rolls, it could "record" the piano playing of famous pianists and composers and play it back fully automatically. This device was called the Welte-Mignon, and with it, the reproducing piano was born. When you listen to this 1912 recording of Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel playing the piano, it is a historic moment. With crystal-clear sound, you can hear their nuanced interpretations of the works they considered the most important in their oeuvre. The pieces were recorded automatically on a modern Steinway grand piano. An acoustic journey back in time and a musical treasure—not just for pianists.

Audiophile Audition –

We’ve reviewed a number of previous CD reissues of new recordings made of historical piano rolls played back on either specially-restored original mechanical instruments, or using an 88-fingered “vorsetzer” rolled up to a modern grand piano and recorded in digital stereo or even a completely redone computerized realization, played back on a Yamaha Disklavier Pro grand piano. (Tacet insists these are not historical recordings, but somehow they seem to belong in this particular section of our site.)

The Welte-Mignon system, patented in 1904, was undoubtedly the most sophisticated and complex of all the reproducing piano technologies. They preserved details of dynamics, touch and phrasing that other systems ignored. The Rube Goldbergish system used a tray of mercury under the keyboard, rubber rollers and ink to indicate the notes and their dynamic levels, and was operated using a plethora of pneumatic hoses (not unlike the Citroens I used to drive). Some of the top composers and pianists of the time cut piano rolls for the Welte company, including Debussy and Ravel, because their results were light years ahead of the primitive disc recordings of that era. The factory in Germany was destroyed in WWII, but a number of rolls and players still exist and some experts at properly setting up the special players have restored them to make possible new stereo recordings of modern grand pianos reproducing the performances of great composers originally recorded in the early years of the 20th century.

The computerized recordings of Rachmaninoff on Telarc were quite convincing (though they didn't originate from Welte rolls), but the Tacet label has approached the leading Welte expert to set up the original sound production mechanism and has recorded the results in excellent modern stereo on a series of CDs now numbering a dozen. Some of the previous efforts from other sources have still sounded quite player-pianoish, and often were marred by the mechanical sounds and leaks in the Welte pneumatic pressure system. These Tacet recordings are free from all of that. The music of both Debussy and Ravel is one of the ultimate tests of the technology, since the pedaling is such an important factor in Debussy and pristine clarity of execution is such a vital factor in the music of Ravel. The two selections composed and performed here by Ravel are not in the least impressionistic or slushy; they are built on precise dance forms. These recordings pass the test extremely well. Note the just-right amount of pedal used by Debussy - coloring the impressionistic tone-painting but not blurring things together. No other piano-roll recordings have that. Also notice Ravel’s lack of synchronization between his two hands in the slow movements. The Sunken Cathedral has long been one of my favorite Debussy works, and although I was thinking of the orchestral versions (or Tomita’s amazing electronic version), I think now I’ll revert to this iteration of the composer’s own piano version. These treasures from the Welte-Mignon should be heard by every piano student.

John Sunier

Classics Today France –

What a miracle! Admittedly, I wouldn’t have started the Debussy section with Children’s Corner, where, at first, the machine seems to stumble a bit. This gives an unfair impression of what is otherwise a miraculous reproduction of these rolls recorded in 1912 by Debussy and Ravel. Unlike the process used to digitize the 1955 Gould and Art Tatum recordings, these are not remastered historical recordings but optimized reproductions from a mechanical piano system. The series is called “The Welte-Mignon Mystery,” and listening to certain pieces on this disc—smooth in execution, with real nuances and resonance—it’s legitimate to speak of a mystery. Missing notes are extremely rare, and the Welte-Mignon process has never sounded like this before.

Tacet tells us that this is “because, for the first time, the Welte-Mignon mechanism has been meticulously restored by the best professional technician, Hans-W. Schmitz.” Debussy, Ravel, and we ourselves owe Hans-W. Schmitz our thanks, because what we hear is spine-tingling when we consider who is playing and under what excellent conditions we can savor the composers’ own interpretations of their works.

In this process, the roll—which also contains dynamic and pedal information—drives a mechanical “player” with wooden fingers covered in felt, positioned above the keys and activated by a pneumatic system. Engineer Schmitz emphasizes the need for extremely precise adjustment of the strike force and roll playback speed. Listening to Debussy’s own performance of La Plus que lente, we have every indication that everything here is calibrated to the nearest micron!

Schmitz clearly explains the unavoidable limitation of the process: “The playback device does not control the volume of each individual note, only the lower and upper parts. Differentiation in dynamics for notes struck simultaneously within chords of the same part is therefore impossible.” This limitation may occasionally puzzle the most discerning ears. The same goes for slight desynchronization, which we cannot definitively attribute to the composer-performer.

But what we had never fully realized before is the consistency of the playback (no jolts in the flow), the respect for dynamics, and the use of the pedal. This is a far cry from the “player piano” in the traditional, “piano bar” sense of the term.

In such high-quality reproduction, Tacet’s recordings—especially when they feature artists (let alone composers) for whom we have no other audio documents—become fundamental heritage of the world’s musical patrimony.

Musically, Debussy surprises with his pianistic expertise: refined control of dynamics within a rather lively musical gesture. There’s no atmospheric effect (no inspired slowdown) in The Wind in the Plain, but an almost disjointed, limping approach to Minstrels, on which I will draw no conclusions, as some of the stumbles on repeated notes seem attributable to the process or a less well-preserved roll.

Ravel the pianist is less subtle and nuanced. Probably a less skilled pianist (dynamic control at the end of the Modéré from the Sonatine), he wanders through his works with a certain nonchalance, frequent desynchronization of the hands, and arpeggios.

Consider the number of discoveries: after an hour, one can confidently say, without fear of error: “Debussy was a better pianist than Ravel.” Who would have thought this could be documented so clearly? I don’t know about you, but it gives me vertigo…

Christophe Huss

___________________________________________________

Original Review in French language

Quel miracle! Certes, a priori, je n’aurais pas débuté la section consacrée à Debussy avec Children’s corner où, au début, la machine semble achopper un peu. Cela donne une image injuste d’une restitution par ailleurs miraculeuse de ces rouleaux gravés en 1912 par Debussy et Ravel. Contrairement au procédé qui a numérisé les enregistrements de Gould 1955 et de Art Tatum, il ne s’agit pas ici d’enregistrements historiques refaits à neuf mais de reproduction optimisée d’un procédé de piano mécanique. La série s’appelle „Le mystère Welte-Mignon“ et à entendre certains morceaux de ce disque, leur déroulement sans heurt, mais aussi les vraies nuances et un rendu de la résonance, il est légitime de parler de mystère. Les notes qui manquent sont fort rares et le procédé Welte-Mignon n’a JAMAIS sonné comme cela.

Tacet nous dit que c’est „parce que, pour la première fois, la mécanique Welte-Mignon a été soigneusement remise au point par le meilleur technicien professionnel Hans-W. Schmitz“. Debussy, Ravel et nous-mêmes remercions Hans-W. Schmitz, car ce qu’on entend donne des frissons, quand on pense qui joue et dans quelles excellentes conditions nous pouvons savourer le regard des compositeurs sur leurs propres oeuvres.

Dans le procédé, le rouleau, qui comporte aussi des informations de dynamique et de pédale, alimente un „joueur“ mécanique aux doigts de bois recouverts de feutre placés en face des touches, actionnés par un système pneumatique; L’ingénieur Schmitz insiste sur la nécessité d’un réglage très fin de la force de frappe et du tempo de déroulement des rouleaux. À l’écoute de la Plus que lente de Debussy par lui-même, nous avons tous les indices nous montrant que la chose est ici réglée au micron près!

Schmitz explique très bien la limite incontournable du procédé „l’appareil de lecture ne règle pas la puissance sonore de chaque note mais seulement de la partie basse et de la partie haute. Une différenciation dans la dyamique de notes frappées en même temps à l’intérieur d’accords d’une même partie est donc impossible.“ C’est cette limite qui intriguera parfois les oreilles sourcilleuses. De même qu’une désynchronisation légère qu’on ne saurait absolument attribuer au compositeur-interprète.

Mais ce dont on en s’était jamais vraiment rendu compte à ce point, c’est de la régularité de la lecture (pas de heurt dans le déroulement), du respect de la dynamique et du jeu de la pédale. On est très loin du „piano mécanique“ dans l’acceptation traditionnelle et „piano bar“ du terme.

Dans une telle qualité de restitution, les enregistrements Tacet, lorsqu’ils concernent des artistes (a fortiori des compositeurs) dont nous n’avons aucun autre document sonore deviennent des héritages fondamentaux du patrimoine musical mondial.

Musicalement, Debussy étonne par son expertise pianistique: contrôle des dynamiques raffiné au sein d’un geste musical plutôt vif. Aucun effet atmosphérique (genre ralenti inspiré) dans Le vent dans la plaine, mais approche quasiment désarticulée et claudicante de Minstrel, sur laquelle je ne tirerai aucune conclusion, car un certain nombre de „culbutes“ sur les notes répétées me semblent imputables au procédé ou à un rouleau en moins bon état.

Ravel pianiste est moins subtil et nuancé. Sans doute moins bon pianiste (contrôle dynamique à la fin du Modéré de la Sonatine) il passe comme un vagabond avec nonchalance à travers ses oeuvres avec une certaine désynchronisation des mains et des arpégements fréquents.

Rendez-vous compte du nombre de découvertes : au bout d’une heure on peut avancer sans craindre de faire une erreur: „Debussy était un meilleur pianiste que Ravel“. Qui aurait pensé voir documenter cela aussi clairement? Je ne sais pas vous; mais moi, cela me donne le vertige…

Christophe Huss