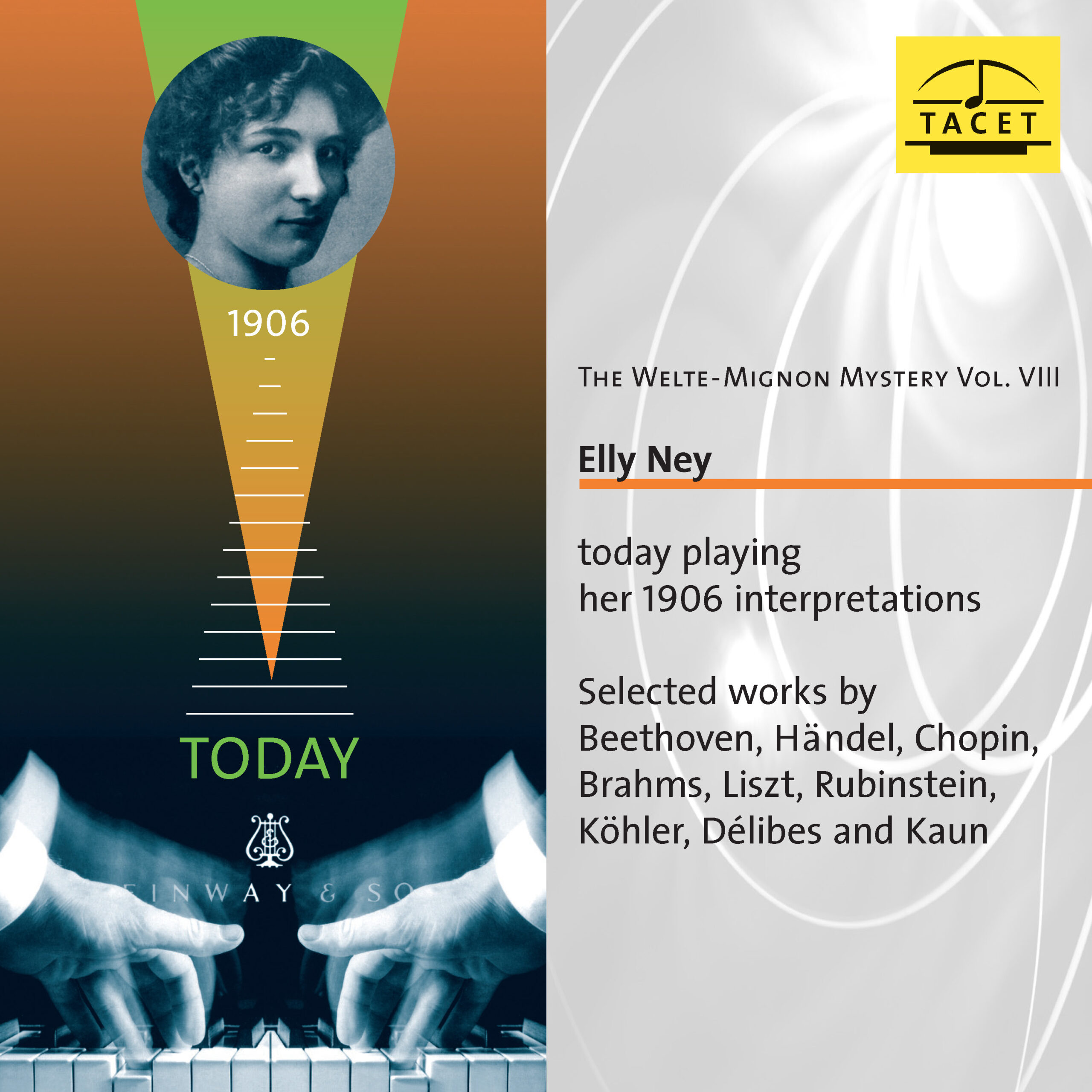

158 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. VIII: Elly Ney

Description

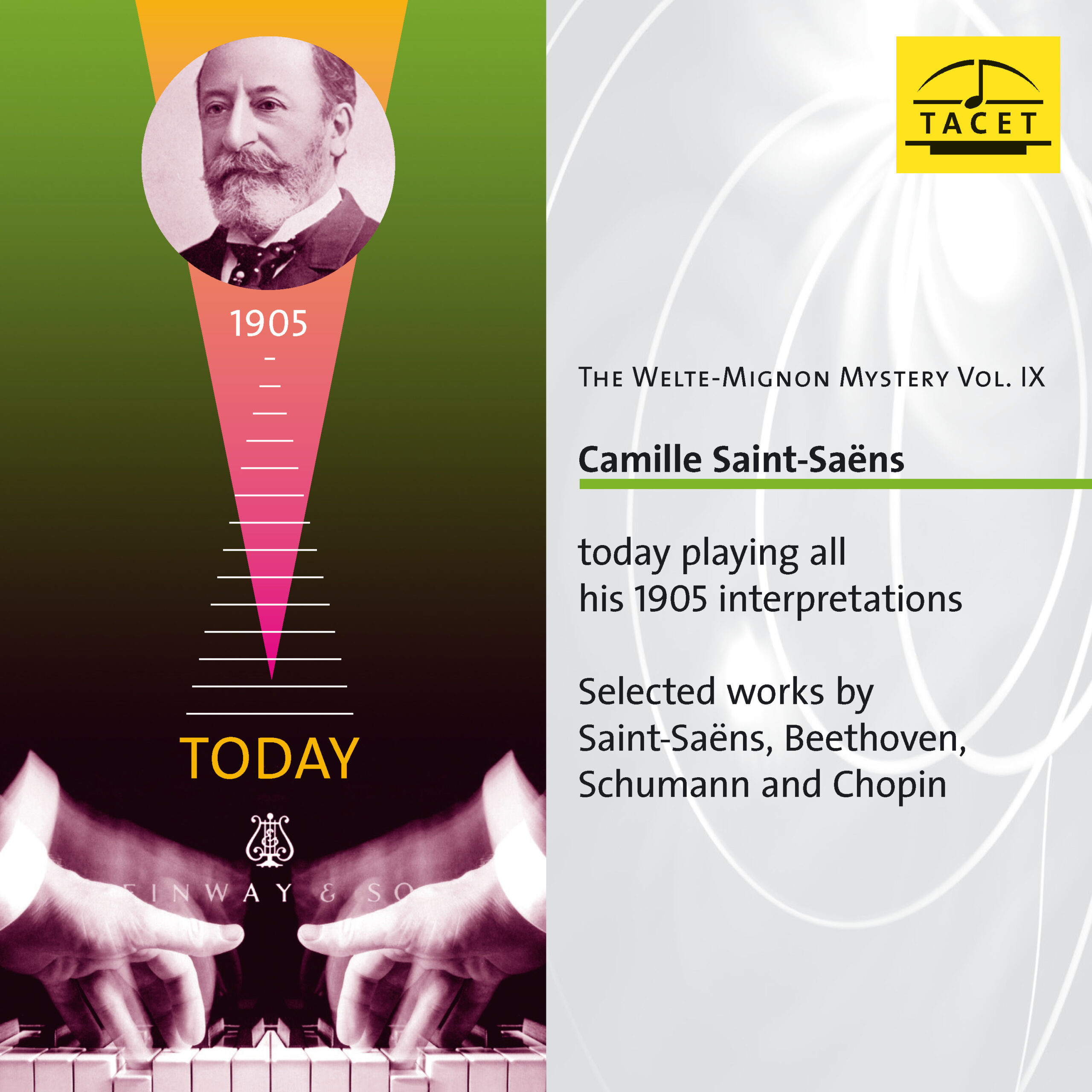

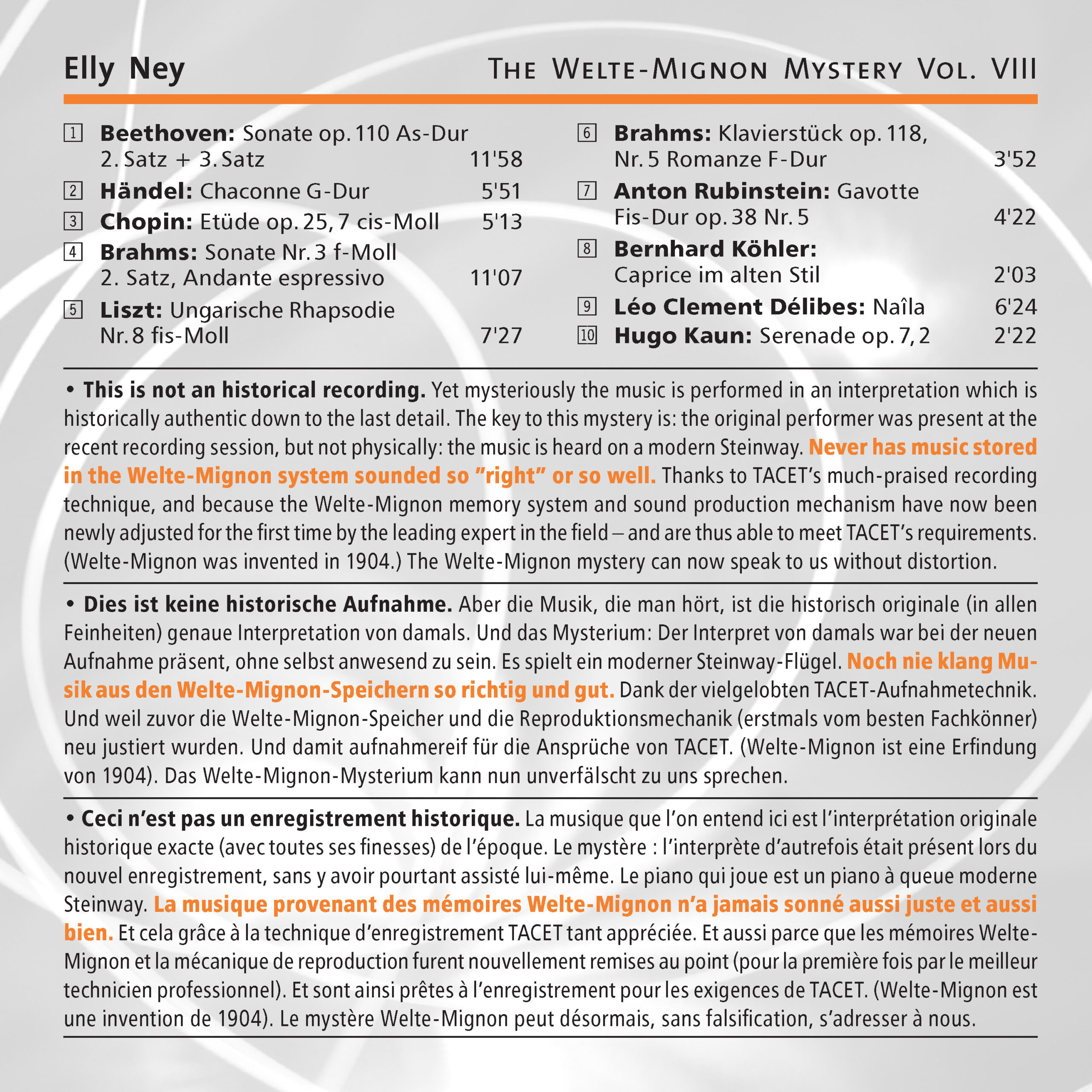

This is not an historical recording. Yet mysteriously the music is performed in an interpretation which is historically authentic down to the last detail. The key to this mystery is: the original performer was present at the recent recording session, but not physically: the music is heard on a modern Steinway. Never has music stored in the Welte-Mignon system sounded so "right" or so well. Thanks to TACET′s much-praised recording technique, and because the Welte-Mignon memory system and sound production mechanism have now been newly adjusted for the first time by the leading expert in the field - and are thus able to meet TACET′s requirements. (Welte-Mignon was invented in 1904.) The Welte-Mignon mystery can now speak to us without distortion.

5 reviews for 158 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. VIII: Elly Ney

You must be logged in to post a review.

Pianiste –

THE LESSONS OF THE PAST

The Magic of the Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… spielen ihre Werke.

Would you like to hear Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, and Reger playing their own works on a modern piano? And how about a "perfect" restoration of the interpretations by the early Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne, and Schnabel? The German label Tacet offers an anthology of rolls recorded by the Welte-Mignon system. The system is simple, but the process of reproduction is particularly complex! In fact, the pieces played by the composers themselves were digitized from the device invented in 1904 by the company Welte & Sons of Freiburg. The perforated rolls of the time captured the touch, pedal play, and the finest nuances. Today, all that is needed is to transfer these recordings onto a concert piano.

It is therefore a real shock to hear, in optimal listening comfort, Debussy’s Children's Corner and some Préludes, as well as Ravel’s Sonatine and Valses nobles et sentimentales, all played by the composers themselves. What lessons can we take away from this? First, the astonishing freedom with which these two geniuses approach their scores! It is also true that Ravel’s playing is not always flawless… But if we look beyond the purely technical aspect, we notice the extreme finesse and personalization of their touches. The dynamics are generally soft, with the fingers seeming to merely caress the keyboard. No brutality whatsoever. The clarity and gentleness are astounding. Other examples are equally striking, such as the two volumes dedicated to Brahms’ works interpreted by Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney, or Chopin’s Etudes played by Pachmann and Paderewski…

The virtuosity of these pianists is staggering, but even more surprising is the passion, the commitment, and sometimes even the coquettishness, the occasional unnecessary ornamentations that some perform almost as if they were tics. From all these master lessons, we learn that the strongest personalities only flourish after a visceral and profound understanding of the works. Schnabel in the waltzes of Josef Strauss and Josef Lanner (who would dare play this today?), Horowitz in 1926 in some Rachmaninoff Preludes, speak to us. Where does the charisma and charm of their interpretations come from? A mystery.

Every year, Tacet releases three or four new CDs from the Welte-Mignon archives. Worth collecting.

S. F.

_________________________________________________

Original Review in French language

LES LEÇONS DU PASSÉ

La magie des Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… jouent leurs œuvres.

Vous aimeriez entendre Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, Reger jouant sur un piano d’aujourd’hui leurs propres Oeuvres? Et que diriez-vous aussi d’une restitution « parfaite » des interprétations des premiers Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne et autres Schnabel? Le label allemand Tacet propose une anthologie des rouleaux gravés par le procédé Welte-Mignon. Le système est simple, mais le procédé de restitution particulièrement complexe! En effet, les pièces jouées par les compositeurs eux-mêmes ont été numérisées à partir de l’appareil inventé en 1904 par la firme Welte & Fils de Fribourg. Les rouleaux perforés de l’époque ont capté le toucher, le jeu des pédales et les nuances les plus fines. Il suffit aujour¬d’hui de transférer ces témoignages sur un piano de concert.

C’est donc un véritable choc que d’entendre dans un confort d’écoute optimal les Children’s Corner et quelques Préludes par Debussy, mais aussi la Sonatine, les Valses nobles et sentimentales de Ravel sous les doigts des compositeurs. Quelles leçons en retirons-nous? D’abord, l’étonnante liberté de ces deux génies vis-à-vis de leurs partitions! Il est vrai aussi que le jeu de Ravel n’est pas d’une justesse infaillible… Mais si l’on dépasse l’aspect purement technique, on s’aperçoit de l’extrême finesse et de la personnalisation des touchers. Les dynamiques sont généralement faibles, les doigts semblent effleurer le clavier. Sans aucune brutalité. La clarté et la douceur sont stupéfiantes. D’autres exemples sont frappants comme ces deux volumes consacrés à des œuvres de Brahms interprétées par Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney ou bien les Études de Chopin par Pachmann et Paderewski…

La virtuosité des pianistes est stupéfiante, mais on est plus surpris encore par la fougue, l’engagement, parfois même les coquetteries, les ornementations intempestives que certains provoquent comme des tics. De toutes ces leçons de maîtres, on retient que les personnalités les plus fortes ne s’épanouissent qu’après une compréhension viscérale et profonde des œuvres. Schnabel dans les Valses de Josef Strauss et de Josef Lanner (qui oserait jouer cela aujourd’hui ?), Horowitz en 1926 dans quelques Préludes de Rachmaninov nous interpellent. D’où proviennent le charisme et le charme insensés de leurs lectures? Mystère.

Chaque année, Tacet publie trois ou quatre nouveaux CD des archives Welte-Mignon. À thésauriser.

S. F.

Pizzicato –

FROM ELLY NEY’S EARLY DAYS

The pianist Elly Ney enjoyed a career spanning many decades and made a name for herself especially as a Beethoven interpreter. The Welte Mignon recordings presented here date from 1906, when the pianist was just 23 years old. The program includes works—unfortunately often only in excerpts—by Ludwig van Beethoven (two movements from Sonata Op. 110), Brahms (Andante from Sonata No. 3, Piano Piece Op. 118 No. 5), Handel (Chaconne in G Major), Chopin (Etude Op. 25/7), Liszt (Hungarian Rhapsody No. 8), among others. All in all, this is a valuable collection that presents over a century-old interpretations in excellent sound quality. Beethoven and Brahms are, of course, the highlights: highly sensitive and deeply emotional moments from a great interpreter! But the powerful, unaffected visions of Chopin and Liszt are also impressive, as is Handel’s marvelous Chaconne. Ney’s outstanding playing and her ability to get straight to the heart of the music without detours remain captivating even today, especially as these interpretations have aged remarkably well and, in the case of Brahms, even seem forward-looking. A significant CD for any collector.

Steff

Klassik heute –

The early days of the Welte-Mignon technology bring forgotten piano composers to light—wonderfully elevated to contemporary standards by the Tacet technician and producer—here performed by a pianist focused above all on the great, unforgettable masters. It is Elly Ney, the widely experienced, priestly, indeed supra-denominational pianist of the Reich and postwar era, who here recalls the chaste miniatures of Bernhard Koehler and Hugo Kaun. The author of the accompanying notes, who writes competently about the performer’s skill as well as occasional lapses and rough edges, has little to convey about these minor composers—and this may be forgiven from the perspective of a knowledgeable (or ignorant) colleague. At the time of these recordings, the Emil von Sauer pupil—later esteemed as the “High Priestess” and “Widow of Beethoven” (but also sometimes ridiculed)—was just 23 years old. Understandably, she played cleaner than in her later years. She had the ability to keep both the score in sight and her fingers in check. Thus, taking into account all the phraseological and tempo-related limitations imposed by the mechanics of the rolls, one experiences Ney here in fine, even excellent form: capable of powerful articulation, but also sensitive to flowing, charming, and gentle passages (Chopin). In short, a fascinating acoustic glimpse for specialists into an era of subjectively innocent piano playing. And to summarize it in feuilletonist terms, it suffices to quote American commentators, who dubbed Elly Ney the “female Paderewski”!

Peter Cossé

Audiophile Audition –

Elly Ney (1882-1968) emerged as a leading exponent of the Leschetizky school of pianism and a became a “high priestess” of Beethoven in her own lifetime. Recording prolifically right to the end of a chequered career--she was indelibly associated with National Socialism as Hitler’s favorite musical artist--Ney made a series of recordings for the Colisseum label that reveal a permanent beauty of tone applied over a smear of faulty fingerings.

But in 1906, shortly after her graduation from classes with Emil von Sauer--the Brahms F Minor Sonata provided her exam piece--Ney gained access to the Welte Mignon studio, along with fellow musicians Carl Freidberg and Artur Nikisch. These are her earliest inscriptions, and they pay tribute to a refined and flexible approach to music, where the independence of the hands and free rubato marked the accepted style of performance.

Ney opens with the two latter movements of the A-flat Major Sonata of Beethoven, Op. 110, taken rather furioso, with Ney’s leaping over the sforzati and not respecting pauses much. She applies a firm hand to the fugue, making it sing even while stumbling over some knotty passages. The G Major Chaconne of Handel--long a favorite of contemporary Edwin Fischer--had been assigned to her by teacher Isidor Seiss, Ney executes brilliantly, a series of distinct pearls. Ney’s rubato in the scho effects of the Brahms slow movement may seem excessive to our tastes, but they were the common romantic license of her day. The Romance from Op. 118 moves as vertically as it does horizontally, the series of trills over a pedal achieving a soft, carillon effect.

The Liszt emerges as stylistically idiomatic as a liquid salon piece that ends with the same flourish as a Brahms Hungarian Dance. Recall that Ney had been hailed as “the female Paderewski.” The Rubinstein Gavotte, another glittery, salon exercise in tricky metrics and a light hand, passes by unostentatiously. Bernhard Koehler remains an unknown entity: his Caprice hums through several octaves in echo, pleasantly forgettable. Hugo Kaun enjoyed more popularity as a turn-of-the-century salon figure, and his tritely sentimental Serenade sounds like third-rate Lehar. The Naila Waltz transcription--later a staple of Geza Anda--enjoys a plethora of color details, the syncopations jaunty and the main melodic tissue suddenly thrust forth among a panoply of chirps and mews.

Reproduced on the modern Steinway D, Ney’s sound comes across as that of natural virtuoso, a lyric, even occasionally flamboyant personality, the Germans’ answer to Teresa Carreno.

Gary Lemco

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

Erst später ein Gespenst

The recordings Elly Ney made in 1906 on the Welte-Mignon piano sound, thanks to the inventive playback techniques of the Stuttgart sound engineer Andreas Spreer, as if they were made in a modern digital studio. They are a small sensation: while they do not entirely dispel the specter of the Reich-era piano grandmother of Hitler’s favor, they do remove that of the “High Priestess” of pathetically grandiose Beethoven playing suggested by her later recordings. Admittedly, the then 24-year-old is audibly a child of her time in her vigorous rubato and the drifting apart of the hands. She also did not shy away from salon pieces, such as a charmingly served waltz by Léo Délibes or Liszt’s bravely executed Eighth Hungarian Rhapsody. The greatest interest, however, lies in two movements from Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 110 and the Andante from Brahms’ Third Piano Sonata—pieces she continued to play into her later years. Here they sound unpretentiously lyrical and without the mannered pre-noting that she later considered a sign of spiritualized interpretation. In the Scherzo of the Beethoven sonata, she masters the virtuosic middle section effortlessly, declaims the introductory recitative of the final movement with eloquence, struggles audibly with the fugue, and only returns to spirited playing in the concluding stretta. Elly Ney’s early recordings are a stroke of luck: a meeting with a young musician who has not yet crystallized into her own monumental self.

Uwe Schweikert