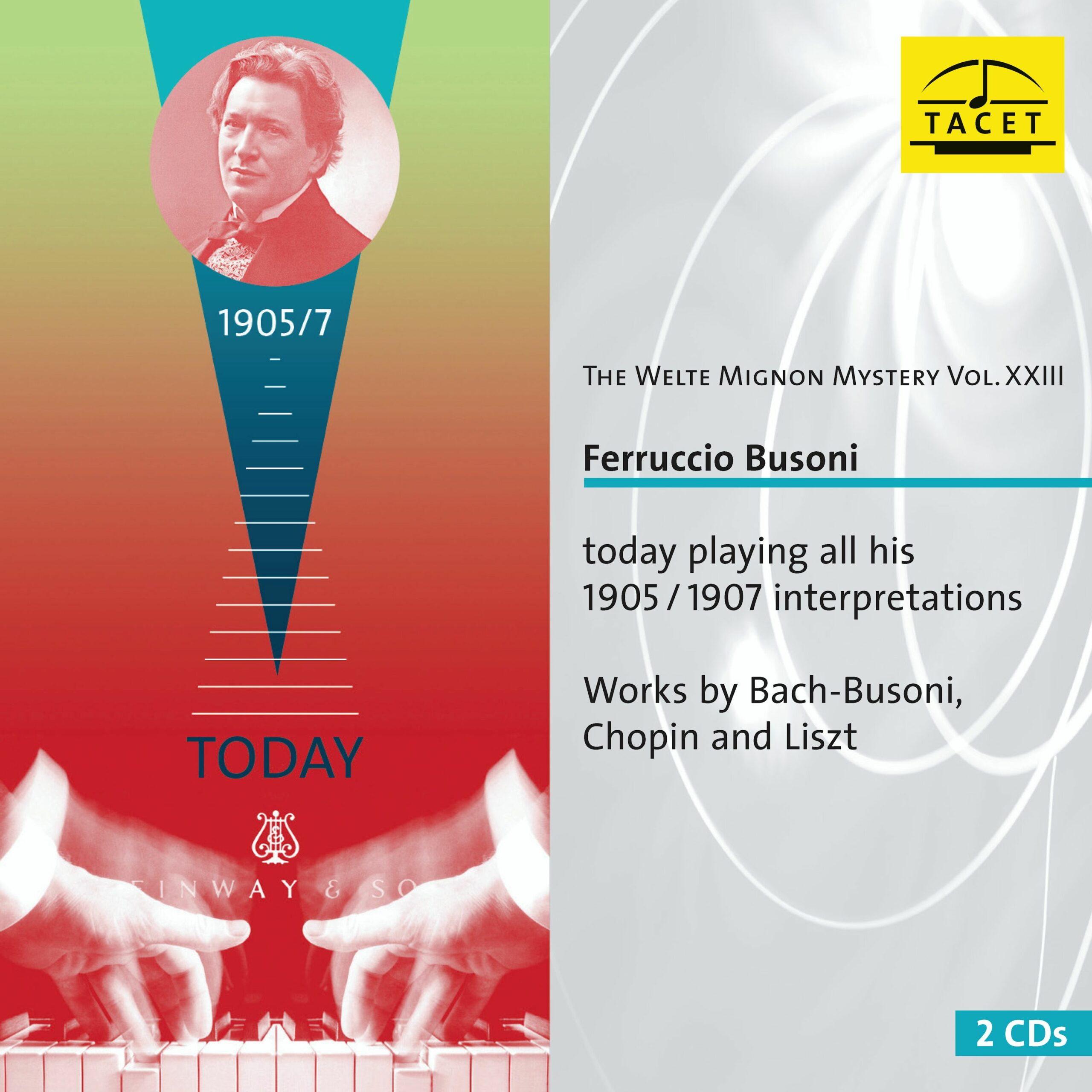

244 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. XXIII. Ferrucio Busoni

Description

For the last time, we dive deep into the 19th century as part of our benchmark collection of Welte recordings.

Born in 1866, pianist and composer Ferruccio Busoni was recommended by Johannes Brahms as a student and was acquainted with countless musicians from Grieg to Tchaikovsky. Today he is best known for his arrangements or interpretations of Bach, Chopin and Liszt. All of Busoni's Welte recordings can be found on this double CD (for the price of one).

Sämtliche Welte-Einspielungen von Busoni finden sich auf dieser Doppel-CD (zum Preis von einer). Damit ist die TACET-Serie „The Welte Mignon Mystery“ abgeschlossen.

Video on the Welte Mignon piano with the expert Hans W. Schmitz

4 reviews for 244 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. XXIII. Ferrucio Busoni

You must be logged in to post a review.

klassik.com –

--> original review

Completely without noise: Busoni plays Chopin and Liszt in 1905 and 1907.

Gramofon Ungarn –

[The following review is an automatic translation of the original Hungarian review, the original in Hungarian follows below].

Das deutsche Plattenlabel Tacet veröffentlicht eine spannende Serie ehemaliger Welte-Mingon-Klavierrollenaufnahmen. Die neueste Veröffentlichung sind die Aufnahmen von Ferruccio Busoni, auf deren Cover steht: „Heute spielt Busoni“. Und das ist wahr. Zum Teil.

Michael Welte begann in Vöhrenbach im Schwarzwald mit der Herstellung von Orchestrien“, Musikinstrumenten auf der Basis von Pfeifen, Schlagwerk und manchmal auch Klavieren. 1872 zog die Fabrik nach Freiburg im Breisgau um. Der älteste Sohn von Michael Welte, Emil, zog 1865 in die Vereinigten Staaten und erfand die Klavierrolle. Eine Reihe von Patenten führte 1904 zur Einführung des Reproduktionsklaviers: Es spielte nicht nur die Noten, sondern reproduzierte auch das Tempo, die Phrasierung, die Dynamik und die Pedalbetätigung – mit einigen Einschränkungen. Mit einer gewissen Straffung, denn dadurch wurde die dynamische Skala etwas zur Mitte hin verschoben und die dynamischen Unterschiede zwischen den Händen wurden angeglichen. Debussy nahm seine vierzehn Stücke im November 1913 auf und schrieb an Edwin Welte: „Es ist unmöglich, eine vollkommenere Wiedergabe als die Welte zu erreichen. Ich freue mich, Ihnen mit diesen Zeilen meine Überraschung und Bewunderung über das Gehörte zu versichern.“

What was true back then is only partially true today. Welte-Mignon roll pianos were very popular in both Europe and America and influenced the playing of many great composers and performers. The technology survived the First World War, but was quickly eclipsed by the Great Depression of 1929-33 and electronic recording technology. So much so that the playing devices, the Vorsetzer, were all destroyed and were only rebuilt much later. Several publishers then brought out compact disc reconstructions of these old documents on modern pianos. The Tacet company began a series of Welte-Mignok reels, which has since become an extensive collection. Perhaps they will later switch to Ampico rolls, which would be important as Rachmaninoff was under contract with this company. That's why he's not on the Tacet Rachmaninoff disc, but the recording of the first version of the Sonata No. 2 with Paul Strecker is very interesting. [...] He is a German pianist and famous teacher, [...] with a very puritanical style, quite distant from the composer, as if Rachmaninoff had been captured by the new world of objectivity.

The Busoni publication is very interesting. Nowadays it is mainly Bach transcriptions that are performed. Of these, only the chorale prelude Nun freut euch, lieben Christen g'mein is included on the album. Then Chopin and especially Liszt. How did Busoni play the piano? Yes and no. Obviously not in its entirety, since the basic knowledge and basic hearing are different, and the Vorsätzer and the instrument, as well as the acoustics, are different, even if the aim is fidelity. These releases are very sterile in sound, as if they sound in an empty space. This is logical, since a machine is playing.

Or not? Not completely, because a lot of things come through. In one of the pieces in Tacet's Welte-Mignon Mystery series, Mahler, Reinecke and Grieg play. Obviously of particular interest is Mahler, who plays Symphony No. V, Movement I, and Symphony No. IV, Movement IV, Ging heut morgen übers Feld, Ich ging mit Lust durch einen grünen Wald. Mahler's definite rhythm and crystal-clear structuring absolutely come through.

In Busoni's case, too, we can clearly hear the former, much softer and freer playing than today. He, unlike many virtuosi of his time, is not overly free, but in the general taste of later years and today, he prefers a less contrasting, essentially softer and more melodic compression.

Today, Busoni's Bach transcriptions seem strong compared to the Baroque, and those who play them tend to perform them in a way that is adapted to the later sound of the great Romanticism. Busoni did not do so, and it should be noted that the sound that for many reasons is now associated with the great Romanticism was not once so. And this is reflected in Busoni's playing, which has more of a lightness of touch. The opening of Liszt's Polonaise No. 2 is a good example. Everyone plays it much more vigorously today. In the same way, it is worth reflecting on La Campanella. There is no question that if there is one performance to be singled out, it is definitely Cziffra's. Many performers of the last many decades have struggled with the difficulties of the piece. Busoni is perhaps slower than all of them, but it's not that we don't feel that he can go faster, it's that we are in another world. It's like looking at a painting from the 19th century, and where now everything is built in, it's largely open nature with few buildings. The contrast is different, the effect of the accents is different, the world is different.

It is to this completely different world that Tacet's excellent series takes you. The present-day voices of the past are certainly relevant, they tell a lot, but they don't give everything back. Sometimes they need more, sometimes less nuance and relativisation. I doubt, for example, that Grieg played the piano with such a gravelly sound, I think that the pedal of his instrument then and now is not the same, and that what he played sounded more romantic. However, a typical composer's approach is pure rhythm and tonal imagery. Mahler's peckish playing is more logical. We don't know exactly what he was like, but it is not important to the extent that he performs orchestral movements and songs, in any case, tight rhythms are a dominant feature.

A magam részéről sokra tartom Felix Mottlt, akiről nem szokás megemlékezni, pedig ő öltöztette zenekari köpenybe a Wesendonck-dalokat. Az ő anyaga Wagner-nyitányokat és zenekari részleteket tartalmaz, feltűnő és igen fontos, hogy milyen lágyan és dallamosan, s milyen nyugodtan játszik. Ez mindenképp megfontolandó adalék, hiszen egy másfajta Wagner-képet közvetít. Ehhez érdemes hozzátenni a legkorábbi releváns Wagner-bejátszásokat, például Karl Elmendorff 1928-ból származó bayreuthi Trisztán és Izolda-felvételét, amelyben Nanny Larsén-Todsen és Gunnar Graarud énekelte a főszerepeket. Mottl zongorás bejátszásai és ez kiegészítik, erősítik egymást.

How did Busoni play the piano? Better known through the recordings, more comfortable than in his later years, more relaxed, softer, with more atmospheric references. The programme is no coincidence either; for understandable reasons, there was a greater emphasis on shorter pieces and operatic paraphrases.

Balázs Zay

_________________________________________

A német Tacet lemezkiadó izgalmas sorozatot jelentet meg a Welte-Mingon cég egykori zongoratekercs-felvételeiből. Legutóbb Ferruccio Busoni felvételeinek kiadására került sor. A borító szerint „ma játszik“ Busoni. És ez igaz is. Részben.

Michael Welte a Fekete-erdei Vöhrenbachban kezdett „orkesztrionokat“, sípokra, ütőkre és néha zongorára is épülő zenegépeket gyártani. 1872-ben a breisgaui Freiburgba költözött a gyár. Michael Welte idősebb fia, Emil 1865-ben az Egyesült Államokra költözött, ő találta fel a zongoratekercset. Szabadalmak sora vezetett a reprodukciós zongora 1904-es bevezetéséhez: ez már nemcsak a hangokat játszotta le, hanem visszaadta a tempót, a frazeálást, a dinamikát, a pedálhasználatot is – némi megszorítással. Némi megszorítással, mert a dinamikai skála szélei felől valamelyest közép felé tolt, továbbá a kezeken belüli dinamikai eltéréseket egy szintre hozta. Debussy 1913 novemberében játszotta fel tizennégy darabját, majd ezt írta Edwin Weltének: „A Welte-készüléknél tökéletesebb reprodukciót elérni lehetetlen. Örömmel biztosíthatom e sorokkal meglepetésemről és csodálatomról a hallottakat illetően.“

Ami akkor igaz volt, ma csak részben az. A Welte-Mignon tekercsekkel működő gépzongorák mind Európában, mind Amerikában nagy népszerűségnek örvendtek, s számos jeles zeneszerző és előadó játékát örökítették meg. Az I. világháborút túlélte a technika, de az 1929-33-as gazdasági világválság és az elektronikus felvételi technika aztán gyorsan háttérbe szorította. Annyira, hogy a lejátszók, a Vorsätzerek mind el is pusztultak, ezeket jóval később kezdték újraépíteni. Több kiadó jelentette meg aztán kompaktlemezen is e régi dokumentumok rekonstrukcióit modern zongorán. A Tacet cég a Welte-Mignok tekercsekből indított – mára gazdaggá vált – sorozatot. Talán később az Ampico-tekercsekre is áttérnek, ez azért lenne fontos, mert Rahmanyinov ezzel a céggel állt szerződésben. Ezért a Tacet Rahmanyinov-lemezén ő nem játszik, roppant érdekes azonban a II. szonáta első változatának felvétele Paul Streckerrel. Ki is ő? Nem a festő. Egy nála idősebb német zongorista és híres tanár, nagyon puritán, a zeneszerzőtől éppenséggel eléggé távoli stílussal, mintha Rahmanyinovot az új tárgyilagosság világa kebelezte volna be.

A Busoni-kiadvány igen érdekes. Napjainkban főképp Bach-átiratai hangzanak el. Ezek közül mindössze a Nun freut euch, lieben Christen g’mein korálelőjáték kapott helyet az albumon. Utána Chopin és főképp Liszt. Megtudjuk, hogyan zongorázott Busoni? Igen is, nem is. A maga teljességében nyilván nem, hiszen más az alapismeret és alaphallás, a hűségre törekvés mellett is más a Vorsätzer és a hangszer, valamint az akusztika. Ezek a kiadványok igen sterilek hangzás terén, mintha üres térben szólalnának meg. Ez logikus is, hiszen gép játszik.

Vagy mégsem? Nem teljesen, mert azért sok minden átjön. A Tacet Welte-Mignon Mystery sorozatának egyik darabján Mahler, Reinecke és Grieg játszik. Nyilván különösen Mahler érdekes, aki az V. szimfónia I. és a IV. szimfónia IV. tételét játssza, valamint a Ging heut morgen übers Feld -t, az Ich ging mit Lust durch einen grünen Wald-t. Abszolút átjön Mahler határozott ritmikája, kristálytiszta strukturálása.

Busoni esetében is egyértelműen halljuk a hajdani, a mainál sokkal lágyabb és szabadabb játékot. Ő – sok egykorú virtuóztól eltérően – nem túlságosan szabad, de a későbbiek és napjaink általános ízlése szerint kevésbé kontrasztra törekvő, alapjában véve lágyabb és dallamosabb összenyomást preferál.

Ma Busoni Bach-átiratai a barokkhoz képest erősnek tűnnek, s akik játsszák, általában a nagyromantika később rögzült hangzásképéhez igazítva adják elő. Busoni nem így tett, s meg kell jegyezni, hogy az a hangzás, ami sok okból kifolyólag ma a nagyromantikához társul, egykor nem ilyen volt. S ezt tükrözi Busoni játéka, melyben több a kedélyesség, a könnyedség. Jó példa Liszt II. polonézének eleje. Ezt ma mindenki sokkal erőteljesebben játssza. Ugyanígy érdemes elgondolkodni a La Campanellán. Nem kérdés, hogy ha egy előadást kell kiemelni, az mindenképp Cziffráé. Az elmúlt sok évtized előadói közt sokan küzdenek a darab nehézségeivel. Busoni talán mindnél lassabb, de nem azt érezzük, hogy nem menne gyorsabban, hanem azt, hogy egy másik világban vagyunk. Olyan ez, mint amikor egy XIX. századi festmény látunk, és ahol most minden be van építve, nagyrészt szabad természet szerepel, kevés épülettel. Más a kontraszt, más az akcentusok hatása, eltérő a világ.

Ebbe a teljesen más világba visz vissza a Tacet kiváló sorozata. Az egykori bejátszások mai megszólalásai mindenképp relevánsak, elárulnak sok mindent, de nem adnak vissza mindent. Néha több, néha kevesebb árnyalás, relativizálás szükséges hozzájuk. Kétlem például, hogy Grieg ennyire szikár hangon zongorázott, szerintem az egykori hangszer és mai pedálja nem azonos, s amit játszott, romantikusabban szólt. Ugyanakkor tipikus zeneszerzői megközelítés a tiszta ritmizálás és hangzáskép. Mahlernél a peckes játék logikusabb. Nem tudjuk, milyen lehetett pontosan, de nem is fontos annyiban, hogy zenekari tételeket és dalokat ad elő, mindenesetre a feszes ritmika mindenképp domináns jellegzetesség.

A magam részéről sokra tartom Felix Mottlt, akiről nem szokás megemlékezni, pedig ő öltöztette zenekari köpenybe a Wesendonck-dalokat. Az ő anyaga Wagner-nyitányokat és zenekari részleteket tartalmaz, feltűnő és igen fontos, hogy milyen lágyan és dallamosan, s milyen nyugodtan játszik. Ez mindenképp megfontolandó adalék, hiszen egy másfajta Wagner-képet közvetít. Ehhez érdemes hozzátenni a legkorábbi releváns Wagner-bejátszásokat, például Karl Elmendorff 1928-ból származó bayreuthi Trisztán és Izolda-felvételét, amelyben Nanny Larsén-Todsen és Gunnar Graarud énekelte a főszerepeket. Mottl zongorás bejátszásai és ez kiegészítik, erősítik egymást.

Hogyan zongorázott Busoni? A lemezfelvételek révén jobban ismert, későbbi időktől eltérően kényelmesebben, nyugodtabban, lágyabban, több hangulati utalással. Nem véletlen a műsor sem, érthető okból hajdanán nagyobb súly esett a rövidebb darabokra, valamint az operaparafrázisokra.

Zay Balázs

Klassik heute –

--> original review

This 23rd volume concludes the major Welte-Mignon edition of the Tacet label, which began in 2004 and has made numerous highly interesting interpretations by pianists and composers of the early 20th century newly restored and available in excellent sound quality played on a Steinway grand piano. Let us briefly outline the basic principle once again: a Welte-Mignon reproduction piano was used to record a pianist's playing (including dynamic subtleties, pedal use, etc.) on perforated paper tapes, on the basis of which the interpretation could then be reproduced mechanically, but including almost all details - in other words, a music machine that could reproduce a pianist's playing largely true to the original. In total, several thousand such recordings were produced, which today provide a fascinating (noise-free) insight into piano playing over 100 years ago.

Intellektuelles Klavierspiel und die Tradition des 19. Jahrhunderts

The last set, which comprises two CDs, is once again a real highlight, namely recordings of the great Ferruccio Busoni (1866-1924), who was not only a legendary piano virtuoso, but also an excellent composer, music essayist and conductor, a truly universal musician. In addition to the fourth of his chorale preludes after Bach, the program includes three pieces by Chopin and above all music by Franz Liszt, whose work was a fixture in Busoni's repertoire. Busoni was regarded as an intellectual, no-nonsense pianist, not a keyboard lion, but an interpreter who emphasized the structures of the music, strived for clarity and did not focus on virtuosity but on the work itself. However, this in no way means that the musical text was sacrosanct for him (exactness is certainly not the essence of these interpretations anyway - here and there you will also notice certain rhythmic irregularities or slightly "clattering" chords); in this respect, he is again clearly in the tradition of the 19th century.

All of this can be understood quite well from the present interpretation - written in July 1905 and March 1907. In Chopin's Raindrop Prelude op. 28 no. 15, for example, Busoni partially adds octaves to the left hand in the minor of the middle section, which lends the music a threatening aura, a very peculiar heaviness. Of course, this must be seen in its historical context, but it would be wrong to merely smile about it. In fact, Busoni obviously understood Chopin's 24 preludes primarily as a cycle in which the fifteenth served as the axis, i.e. it is less about an effect than about more meaning; the interpretation results from his perception of the work as a whole, even if this is done with means that are no longer used today. His recording of Chopin's A-flat major Polonaise op. 53, on the other hand, seems rather restrained, slowed down.

Meisterhaftes Gestalten großer Zusammenhänge

As already mentioned, it was Liszt's music that Busoni was particularly interested in, and some of these interpretations are truly great moments, exemplified perhaps by the Norma Fantasy. Here we can see what really defines Busoni's art, and that is especially his sense of creating large contexts, his ability to bring out the dramaturgy of the music: at any point in time, you know exactly where you are (in the course of the piece), Busoni's sense of the "direction" of the music is exorbitant. His playing is orchestral, rich in tone colors and nuances, masterful in following the melos, hearing out the harmonies, considering Liszt's ornamentation as a coloration, but without bringing it to the fore to such an extent that it overwhelms the music. It is also remarkable that the immense pull that Busoni creates (especially towards the end) is not due to the fact that he is particularly forced (he doesn't actually do that here any more than in Chopin's Polonaise), but because he is extremely clever in his dosing and disposition, and so he can even afford to soften the very last chord without jeopardizing the final effect in the least. This masterly interpretation alone makes the purchase of the CD worthwhile. It is just a pity that no interpretations of (even) larger-scale works by Busoni have survived.

Faszinierende Aufnahmen

In addition to an introduction to the Welte-Mignon method, the accompanying booklet provides a good classification of Busoni, his piano playing and the interpretations collected here in particular. Only the track list should have been a little more careful: the fact that it is not Chopin's Polonaise "op. 53 No. 6" is clear anyway, but even in the case of Liszt's Mélodies hongroises after Schubert, for example, a reference to the fact that we are only dealing with the middle movement would not have hurt. However, this should not detract from a fascinating document of historical piano playing and great music-making.

Holger Sambale

Pizzicato –

--> original review

Tacet had not released a new installment of its Welte Mignon Mystery series for almost three years. Now follows a double album with Ferruccio Busoni playing music by Bach, Chopin and Liszt. He had recorded the Welte Mignon rolls in 1905 and 1907, which are now brought to life as a historical document without historical sound. Busoni’s Liszt interpretations are especially remarkable, showing his amazing pianistic abilities. Especially for pianists who associate Liszt with loudness, these recordings are teaching pieces worth taking to heart.

Remy Franck