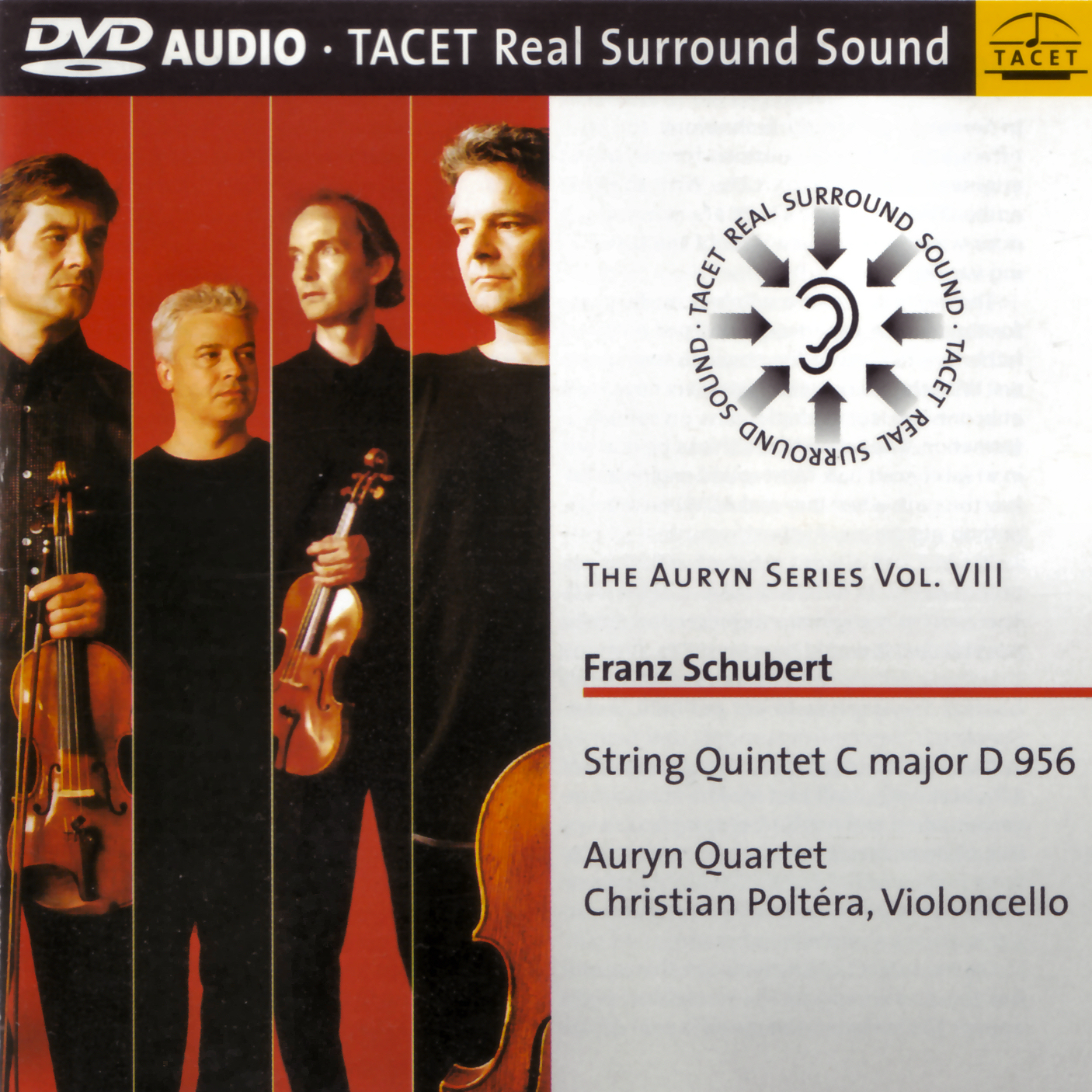

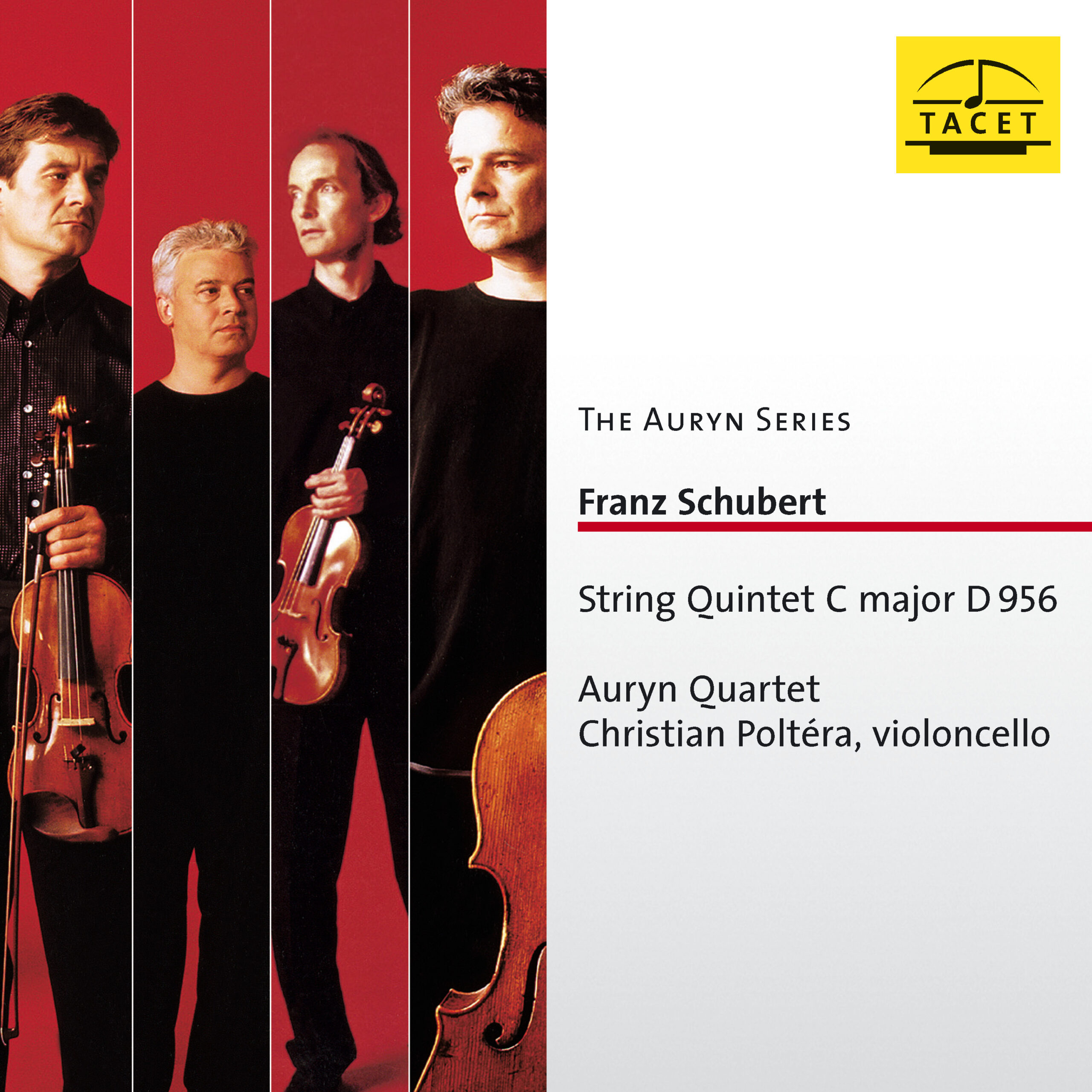

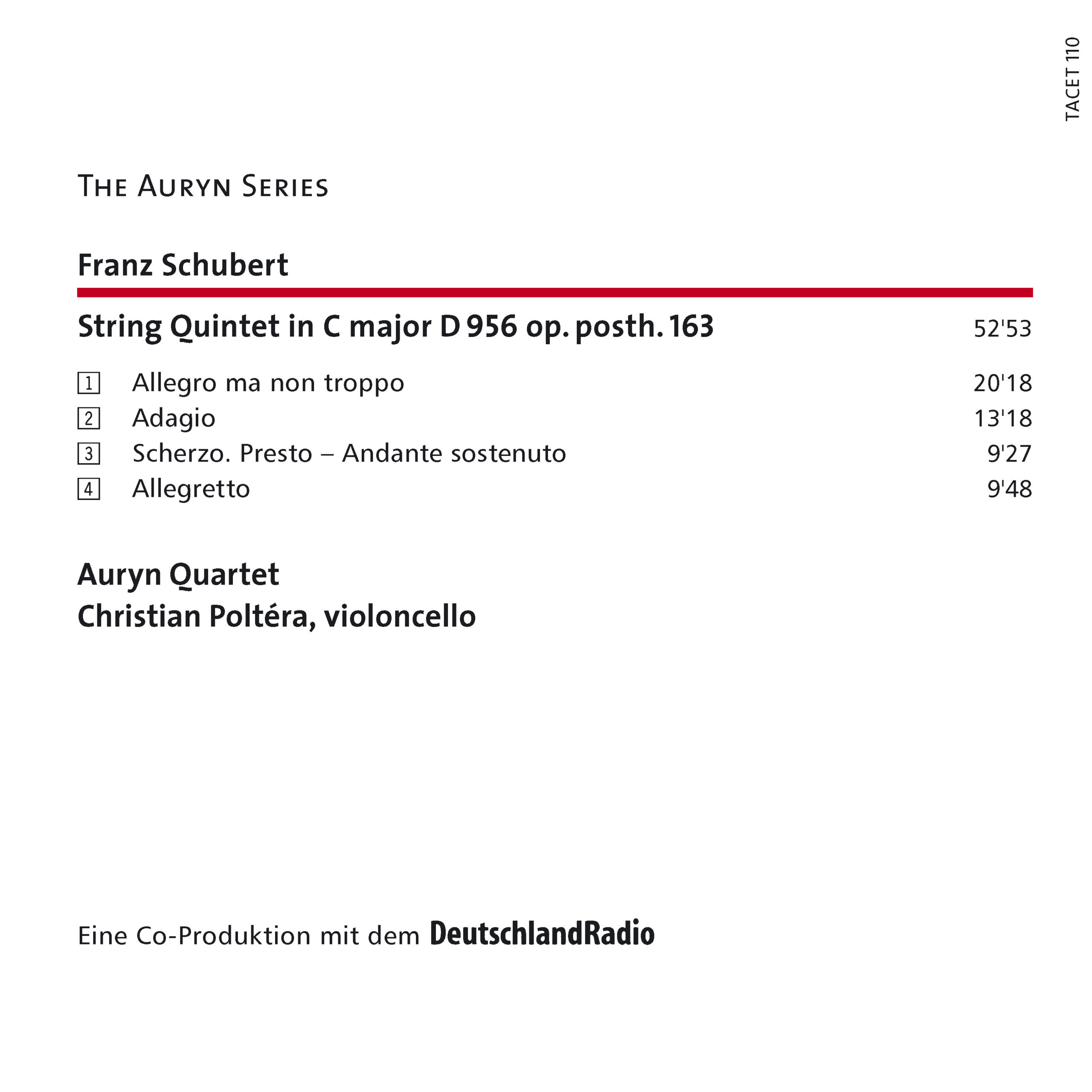

110 CD / Franz Schubert: String Quintet C major D 956CD /

The Auryn Series Vol. VIII

Franz Schubert

String Quintet C major D 956

Auryn Quartet

Christian Poltéra, Violoncello

EAN/barcode: 4009850011002

Description

"BEST RECORDING: What needs many words when Franz Schubert's String Quintet in C major begins to sound and one may be sure: Whoever goes to it delivers himself to the spirit of the music and to his own heartbeat. The Auryn Quartet, which has been in existence for 20 years, spreads its wings of thought wide open with a calm pulse into a paradise full of tragedy." (Hessisch-Niedersächsische Allgemeine)

9 reviews for 110 CD / Franz Schubert: String Quintet C major D 956CD /

You must be logged in to post a review.

ResMusica.com –

Ah! If Franz Schubert had possessed Auryn, the amulet that grants intuition to its bearer (from Michael Ende’s The Neverending Story), perhaps he might have lived just a little longer to give us countless more emotions… Emotions without end, eternal and essential to our lives as music lovers! A genius like this should never have died at thirty-one — it is not fair, as all Schubertians worldwide will affirm. Perhaps then we might have heard true and great operas? Symphonies even further ahead of their time, trios, quartets, quintets of still greater accomplishment — and why not even more powerful lieder…

But we cannot rewrite History, and we must content ourselves with his most beautiful creations. Again and again, the Quintet in C belongs to that special category of works that hold a unique place in the heart and mind of the music lover. Which ensemble, small or great, has not felt both the duty and the desire to bring it forth, imprinting upon it their touch, their genius, their seriousness, their technique, and ultimately their soul. To play Schubert well, one must first truly want to, then absorb him, then step back — in order to return stronger, more convincing.

The Auryn Quartet, we dare say, has understood Schubert completely. This German ensemble strikes in its playing the perfect balance between grace, power, technique, and understanding of the work and its demands. Supported by a marvelous Christian Poltéra on cello, the dialogue between the two cellos becomes a musical rarity in the genre — everything is there: emotion, tempi, the highs and lows transcribed with utter perfection. Throughout this interpretation the ensemble lavishes us with their artistry.

What more can be said? We already have so many versions of this quintet in our collections. And yet, once again, this interpretation is worth the detour. Once again we will succumb, listening in wonder to this masterpiece with the conviction that we have not missed out on something great and magnificent.

Christophe Le Gall

_____________________________

franzöaische Originalrezension:

Ach ! Si Franz Schubert avait possédé Auryn, l’amulette ayant le pouvoir de donner de l’intuition à celui qui la porte (« L’Histoire sans fin » de Michael Ende), peut-être aurait-il vécu juste un petit peu plus longtemps pour nous donner de nombreuses autres émotions … Emotions sans fin, éternelles et indispensables à notre vie de mélomane ! Un génie pareil ne se devait pas de mourir à trente et un an, ce n’est pas juste, tous les schubertiens du Monde le confirmeront. Peut-être alors aurions-nous pu entendre de vrais et grands opéras ? Des symphonies encore plus en avance sur leur temps, des trios, quatuors, quintettes encore plus aboutis et pourquoi pas des lieder encore plus puissants …

Mais nous ne pouvons refaire l’Histoire et nous devons nous contenter de ses plus belles créations. Toujours et encore, le Quintette en ut appartient à cette catégorie d’œuvres à part dans le cœur et la pensée du mélomane. Quelle formation, petite ou grande, n’a pas eu le devoir et l’envie de l’accoucher en lui imprimant sa patte, son génie, son sérieux, sa technique et son âme finalement. Pour bien jouer Schubert il faut effectivement déjà le vouloir, s’en imprégner puis s’en éloigner pour revenir plus fort, plus convaincant.

Le Quatuor Auryn a, nous osons le dire, tout compris à Schubert. Cette formation allemande a dans son jeu l’équilibre parfait entre la grâce, la puissance, la technique et la compréhension de l’œuvre et de ses enjeux. Aidée d’un merveilleux Christian Poltéra au violoncelle, le dialogue des violoncelles est une rareté musicale dans le genre tant tout y est : émotion, tempi, les hauts et les bas sont transcrits de manière parfaite. Tout au long de cette interprétation la formation nous abreuve de son talent.

Que dire de plus, nous avons tant de versions de ce quintette dans nos discothèques. Pourtant, une fois de plus, cette interprétation vaut le détour. Une fois de plus nous craquerons et nous écouterons émerveillés ce chef-d’œuvre avec la conviction de n’être pas passé à côté de quelque chose de grand et merveilleux.

Christophe Le Gall

Bangkok Post realtime –

A magical and eloquent performance

There is plenty of great music waiting to be written in the key of C major, Schoenberg used to remind his students; but what are the chances of anything ever again being composed in that key to compare with Schubert′s string quintet, written in the year of his death at the age of 31? Like Mozart′s The Magic Flute it contains melodies that will charm casual listeners, seemingly simple tunes that become miraculously beautiful with further hearings, but also strange, often abrupt shifts in expressive tone that continue to tantalise those who have lived intimately with the music for decades.

There have been many recordings of the quintet covering a broad range of interpretive approaches. Two of the most celebrated were made in the days before stereo _ the Stern/Schneider/Katims/Casals/Tortelier account recorded at the 1953 Prades Festival, and the one by the Hollywood Quartet with Kurt Reher playing the second cello. More recently there have been distinguished versions by the Alban Berg Quartet with Heinrich Schiff, the Juilliard Quartet with Bernard Greenhouse, the Emerson Quartet with Mstislav Rostropovich, and this performance by the Auryn Quartet with Christian Poltera. And these are only the ones that have found their way into my collection.

Although the Auryn Quartet disc was released in 2001, it has been hard to get hold of in many parts of the world. Until recently you could seek it in vain on the websites of most classical CD vendors. Such limited availability was unfortunate because it is a masterful account in the league of any of the performances named above.

The Auryn Quartet with Poltera stand out even in such lofty company for the expressive flow that they bring to this long work with its many emotional contrasts. The transition from the highly agitated music that opens the first movement to the sublime melody that puts it to rest is one of the great magical moments in music. An eloquent performance like this can make you experience a kind of spiritual shifting of gears as you listen to the passage that follows, a musical absolute of a kind that only Schubert could have created.

The Auryns are magnificent here. The theme is played more slowly than in many performances, and contoured so naturally that it gives the impression of being sung. The delicacy of the playing at the point (after 2:43) where the theme is repeated an octave higher is unique among the recordings that I have heard. In this passage the classic Prades Festival and Hollywood Quartet accounts sound almost matter-of-fact by comparison.

The Adagio second movement, in its ethereal E major key, is shaken by an even more extreme emotional change. After music of hypnotic tranquillity, a long melody unwinding slowly and dreamily, propelled by cello pizzicati and birdsonglike comments from the violin, there is a sudden, violent outburst (beginning here at 4:37) that seems to come out of nowhere. Some commentators hear it as anger, but to me it expresses passionate yearning, a desperate desire for something that cannot be had, and after expending itself it retreats to give way to the music that opened the movement, subtly transformed.

The Auryn players are more inward, less dramatic in their interpretation of this singular movement than most of the others cited above. Their account of the nocturnal music that opens and closes the movement is as perfectly realised as any I have heard, but in the impassioned middle section I missed the urgency of the Prades Festival (complete with Casals′s grunting) and especially Emerson/Rostropovich.

The third movement reverses the pattern of the Adagio. It′s a muscular scherzo, athletic and high-spirited, that suddenly subsides (at 3:42 here) for deep and solemn meditation before springing back into action, kicked off by a powerful tremolo. It is splendidly played here, as is the folk-accented concluding Allegretto. Listen to the Viennese lilt that the Auryn players bring to the music, with their slight agogic pauses in the folk dance-like passages; and to the intensity with which they allow the charge accumulate as the harmonic tension builds after 3:40 before being released by the return of the opening theme.

There is, of course, no such thing as a best performance of Schubert′s C-major String Quintet. Each of the recorded versions mentioned has its own special glories, as do many others in the catalogue (the Borodin Quartet with Mischa Milman on the Teldec label, for example). But if I were having to make do with a single recording right now, this Auryn Quartet/Poltera account would probably be the one that I would reach for. It is also available from Tacet as a surroundsound DVD Audio disc, which I have not heard. The recorded sound on this CD, however, is so fine that I don′t know how it could be improved upon.

Ung-Aang Talay

Crescendo –

With Schubert’s C-major Quintet, the Auryn Quartet has now presented a highlight of Schubert’s chamber music on DVD. Once again, recording engineer Andreas Spreer has placed the musicians in a circle around the listener, and this time the arrangement shows a (deliberate?) effect on the musical shape of the work. For the artful interplay of the quintet often becomes a contrasting opposition, created by sounds coming to the listener from front and back. Above all, the cellos are set against the violins and viola. The result is an entirely new, “unheard” quintet, presented with the usual authority and mastery of the Auryn Quartet.

KH

Gala –

In the final months of his life, Franz Schubert composed the tension-filled String Quintet in C major. It shifts from floating calmness and song-like lyricism to dramatic energy and stormy accompaniment. The Auryn Quartet, with Christian Poltéra on cello, masterfully interprets this composition shaped by contrasts, highlighting its delicate tragic beauty.

Rondo. Das Klassik & Jazz Magazin –

Hardly any work of art is capable of offering humans as much consolation as Schubert’s String Quintet in C major. Created in a single burst of productivity during Schubert’s final months in 1828, this monumental work is a drawing from the depths of inner life, an expression of Schubert’s emotionally strained state, and a magnificent testament to his genius. The Auryn Quartet, joined by cellist Christian Poltéra as the fifth voice, pursues this mystery with great sensitivity. The musicians impress with their meticulous attention to detail, precision in dynamics, tonal brilliance, and transparency within the sound structure. Moreover, they do not—like many famous colleagues—treat the repeat signs in the score carelessly.

The proportions of the work are thus preserved and not distorted. Any trace of sentimentality is avoided, and no cheap display is allowed, even though they approach the Scherzo with a “Brahmsian” force and their bright enjoyment of some wild fff passages in the Finale is unmistakable.

Yet the ethereal quality, the dreamlike gestures, the inherent ambivalence of this composition—here they are not fully captured. It seems almost elusive.

Teresa Pieschacón Raphael

Stereoplay –

The Auryn Quartet has by now secured its place among the foremost international string quartets. It is, however, highly revealing of the repertoire policies of the major record companies that an ensemble of this caliber found no home with DG, EMI, or Philips, but entrusted its outstanding recordings of Schubert, Schumann, Mendelssohn, Beethoven, and Britten to smaller, more adventurous labels. Now the Auryns, joined by Christian Poltéra as second cellist, present a top-class recording of Schubert’s String Quintet – arguably the most significant chamber work of the post-Beethoven 19th century, unless one prefers to crown Schubert’s G-major String Quartet. What is so compelling here is the fascinating balance between a near-symphonic generosity of architecture and sound, and a meticulous chamber-musical illumination of the structure, which opens up ever new and surprising perspectives. The dynamic range is extremely wide, at times leading to almost Brucknerian waves of intensity, and at others laying bare, with disquieting clarity, the expressive ambiguity and fractured character of this music – in the Adagio, in the middle section of the Scherzo, and most strikingly in the Finale (which reveals itself, not only at the end with its famous grace-note D-flat, as more desperate than cheerful). A profoundly affecting interpretation, all the more so because it avoids any hint of mannered intent.

Alfred Beaujean

Hessisch Niedersächsische Allgemeinene Zeitung –

BEST RECORDING

What needs many words when Franz Schubert's String Quintet in C major begins to sound and one may be sure: Whoever goes to it delivers himself to the spirit of the music and to his own heartbeat. The Auryn Quartet, which has been in existence for 20 years, spreads its wings of thought wide open with a calm pulse into a paradise full of tragedy.

Siegfried Weyh

Musik und Theater –

Those who have Schubert’s String Quintet in mind from the legendary live recording at Prades—with Casals and Paul Tortelier, Isaac Stern and Alexander Schneider, and Milton Katims—know the mysterious, unfathomable magic of the Adagio, and the equally dance-like yet defiant force of the closing Allegretto. Few other recordings are likely to please such listeners so readily. Yet how the Auryn Quartet, with Zurich cellist Christian Poltéra, performs the reprise in the Adagio that swings between heaven and hell—so tender and bitter, so yearningly retrospective, still painful yet exhaling relief after the Fortissimo outbursts—is something every lover of Schubert’s chamber music should hear. A true delight! The transparently worked sound reveals the structure of the work, the finely attuned balance, the delicate exploration of the secret of the opening chords in the first movement, the occasional turn toward a rather rough symphonic weight in the Scherzo. The handling of the Finale could perhaps be more audacious, yet it builds to a gripping concluding brio; even in the stubborn friction of the last two notes, the composer’s fractured soul reveals itself.

Elisabeth Richter

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

Even the harshest critics have sung hymns about Schubert’s String Quintet in C major, Op. 163, from his final year, 1828. “Nowhere is Schubert further from the earth… We weep without knowing why, because we are not yet as we are promised to be by that music,” wrote the otherwise rarely effusive Theodor W. Adorno. For Alfred Einstein, the piece was a key work: “When the C-major triad swells at the beginning,” he wrote, “when it dissolves into a diminished seventh chord only to return to the pure heaven of C major, we feel that the gate of Romanticism has mysteriously opened.” A forerunner of Romanticism? Certainly, Schubert here pushed boundaries of expression and form. Unprecedented is the time already taken by the first movement; the Scherzo is disrupted by a contemplative, (death-)serious Trio. This is how one who had touched other spheres described it. Even today, the astonishing power of the music can be conveyed, provided it is performed with the sound sensitivity and inner tension demonstrated by the Auryn Quartet, reinforced by cellist Christian Poltéra. When the first violin in the Adagio climbs ever higher, one can sense how close Schubert must already have been to heaven.

fab