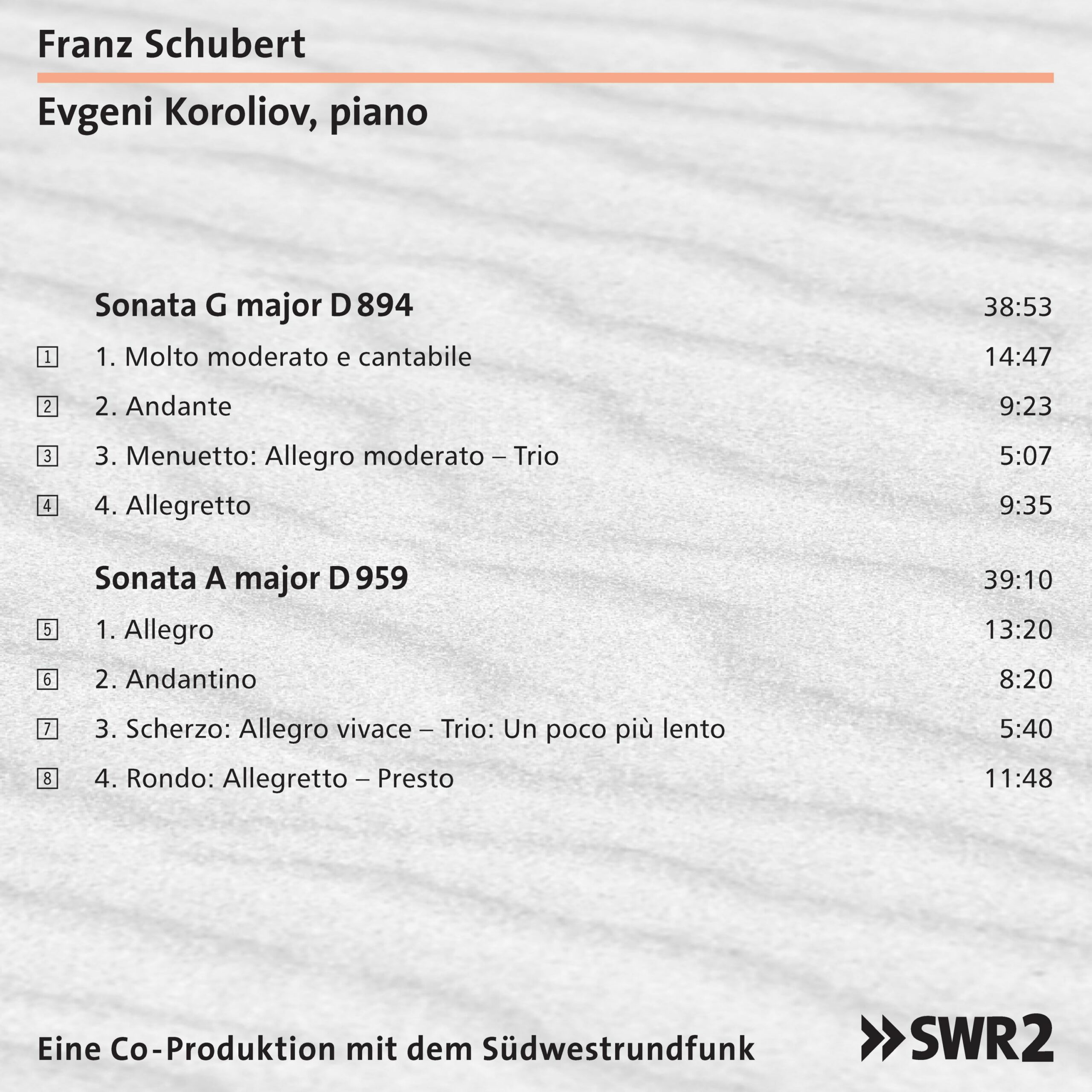

979 CD / Franz Schubert: Sonatas D 894 & D 959

Description

There are already two Schubert recordings by Evgeni Koroliov on TACET. The recording of the Gran Duo D812 and the Fantasy in F minor, D. 940 with his wife (TACET 134) received the "Choc" of the French journal Le Monde de la Musique, amongst other awards. The Japanese magazine Intune wrote the following about the Sonata in B-flat major, D. 960 and the Moments Musicaux (TACET 46) "... Koroliov's technical command of the piano is total... He plays Schubert's Schubert, not his... This is major piano playing... Highest recommendation!" This hits the nail right on the head and applies in equal measure to his new Schubert recording being presented here - a co-production with the SWR.

8 reviews for 979 CD / Franz Schubert: Sonatas D 894 & D 959

You must be logged in to post a review.

Concerti –

--> original review

More than a decade and a half after his recording of Franz Schubert’s Sonata in B-flat major, Evgeni Koroliov has now set down the A-major Sonata D 959 and the G-major Sonata D 894. He does not impose himself, he does not grandstand; he remains true to himself. If one looks for kindred spirits, one will most readily find them in Mitsuko Uchida or András Schiff. Koroliov sees in Schubert above all the lyricist, the vulnerable soul. He avoids extremes (and also omits the exposition repeat in the first movement of D 959), and he romanticizes discreetly in the form of small hesitations. Indignation in Koroliov always has something conciliatory about it; his love of the songful comes to the fore especially in secondary themes or in the Andante of the G-major Sonata. The contrasts in the inner movements of the A-major Sonata are captured clearly and convincingly. A very sound-sensitive, richly colored interpretation, one that would have deserved a more spacious, freer sound image.

Christoph Vratz

NDR Kultur, Welt der Musik –

A Schubert of charm, yet full of contradictions, contrasts, and fragility. One senses that in this Scherzo from the A-major Sonata D 959, Evgeni Koroliov has mentally placed himself inside Schubert’s psyche. There is no pathos here; Koroliov’s Schubert sounds uncompromising, yet at the same time deeply sympathetic to the composer’s many facets: his compositional mastery, his vulnerable soul, his melancholy, his longing.

Elisabeth Richter

International Classical Music Award –

In the Solo category, the choice fell on Evgeni Koroliov’s recording of the Schubert sonatas D 894 and D 959.

Preis der deutschen Schallplattenkritik –

Peter Cossé

Audio –

This CD is a gift for everyone who loves the music of Franz Schubert! And I do not hesitate to speak of an ideal interpretation. The Hamburg-based pianist Evgeni Koroliov achieves the difficult-to-attain miracle of opening up, with the very first chord of the G-major Sonata (D 894), a vast space for Schubert’s universe of sound and time. It seems as if the music simply plays out of him; so naturally, so singing and flowing do the broadly conceived forms of these eight sonata movements unfold. While the G-major Sonata has a more emphatically lyrical character, the penultimate A-major Sonata (D 959) expresses a more dramatic stance—and Koroliov makes both aspects audible and palpable. Indeed, more than that: the common image of Schubert as primarily a melodist is noticeably fractured in this work—just listen to the second movement. Time and again there are abrupt modulations that lead the listener away from an apparent idyll and allow glimpses into the abyss. Thanks to the excellent recording technique, the sound also moves along the “space–time” axis appropriate to it, enabling this music to unfold fully. In this way, the listener experiences that feeling so characteristic of Schubert: a sense of limitless time; one can be drawn into this sound world and, in the best sense, “lose oneself” within it. That we are able to present you, dear readers, with the seventh movement (“Scherzo Allegro vivace”) from this A-major Sonata as track 14 on AUDIOphile Pearls Vol. 8 is one of those unexpected strokes of good fortune that occasionally occur when producing a magazine and an AUDIO cover CD.

Andreas Lucewicz

Klassik heute –

Evgeni Koroliov’s Schubert interpretations in volume no. 15 of the Tacet series devoted to him virtually compel a closer look at the miraculous work in G major (D 894), published as a “Fantasy Sonata.” The coming and going of the figures invented by Schubert and brought to sounding life represents, in the truest and multiple sense, a striking encounter. On the one hand, on the historical side, the composer appears as a carefully shaping master of romantic spirits. In his willingness to open even his inner self, the creator of sound exercises and excites himself as a dreaming, dancing, yearning first-person narrator, with all the possibilities of finding a balance between the expressive poles of pain and well-being, of drama and cheerfulness, right up to the decorous limits of exuberance. Along this tension arc—at times taut, at times relaxed—Alfred Brendel moves in his Philips recording from the 1970s with the assurance of a musician who seems to embody intellect and feeling in unity: for example, by creating space and reflection through sensuously placed chordal blocks in the first movement, but also in his successful effort not to lose sight of the musical object, as Sviatoslav Richter arguably does in his truly decelerated experiments of thought and finger.

To this day, I have experienced Evgeni Koroliov in all his performances as a man of artistic incorruptibility—a pianist who approaches a score in a brooding, probing manner, perhaps even with meticulous research, and who in his appearances hardly distinguishes between a studio filled with an imaginary audience and a concert hall closed to the public but offering studio-quality conditions. Once Koroliov has arrived at results he finds justifiable, he seems to pursue his path in satisfying solitude. He reveals himself in harmony with the course of musical events he has worked out, without ever entering an artistic election campaign by begging for recognition—let alone blind allegiance—through this or that pianistic trick. The first movement of the G-major Sonata takes on a rather astringent hue. The friendly chord groupings unfold in a very peculiar mixture of laconic and subtly pressing, glowing tempering. The subsequent enlivening and liquefaction of the material, right up to dance-like lightness, are unfolded and monitored by Koroliov as a causally linked chain moving forward and, over the course of this large-scale movement, also in their recurring passages. This atmosphere-creating supervision of all parameters present in the text remains, in my view, binding for the pianist’s interpretative handling of all the tasks posed here by two sonatas so rich in sonic and kinetic facets. Different approaches to smaller Schubert units can be traced above all in interpretations of the minuet movement of the G-major Sonata. Most of the interpreters mentioned below place the chordal blocks resolutely, not infrequently with a tendency toward almost punishing hardness. Ingrid Haebler, for example, sets the accents with a severity bordering on the militant, whereas Koroliov, to my ear, ventures a more flexibly nuanced approach to the old-fashioned minuet gesture. In the Trio, by contrast—one of the most touching trio sections in all of music literature!—Ingrid Haebler opts, especially in the second part of the lyrical interpolation, for a discretion of sweetness that could scarcely be imagined or executed more gently buoyant.

With the final movement, most interpreters face their own particular struggle. Only rarely do they succeed in drawing convincing conclusions from the alternation between thematic vividness and an almost improvisatory fluency. Notable deficiencies often appear in matters such as the touch on the signal notes repeated in the main theme, or the accompanying comments to be dabbed out by the left hand. Koroliov—at least it appears so here—lacks a portion of humor, or at least a small dose of nonchalance, to be able—like Alfred Brendel—to explore this movement to its furthest corners of vital melody and rhythm. With Brendel, one may marvel at the left-hand punch lines as if the performer were not playing keys, but tiny trampolines built into the concert grand.

The by now certainly large Koroliov “community” needs no special recommendation of this release, for a series—one knows this from television seasons—under favorable circumstances soon becomes part of everyday life. But Koroliov’s playing should not only benefit his regular audience; it should also be of value to all music lovers who wish to engage more deeply with Schubert’s piano compositions and who repeatedly find themselves enriched through comparative listening.

Peter Cossé

Hessischer Rundfunk, hr2 Kultur –

Tacet has devoted an entire series of piano recordings to the Hamburg-based pianist Evgeni Koroliov; the newly released Schubert recording is no. 15 in this series. But in this case it is not about presenting a rarity or something unusual; here Schubert’s music and Evgeni Koroliov’s interpretation are allowed to speak entirely for themselves. He has chosen two late Schubert piano sonatas: the Sonata in G major and the Sonata in A major, D 959. What distinguishes this piano music is that Schubert has here found his own language: while there are still rough passages in the wake of Beethoven, Schubert sets particularly beautiful melodies against them as a contrast—and knows how to cast all of this into truly large forms.

Evgeni Koroliov shapes these contrasts beautifully; above all, however, he possesses a very delicate and subtle touch that makes this music sing—and Schubert himself once gladly accepted just that as special praise for his own piano playing. This cantabile manner is what characterizes Evgeni Koroliov’s Schubert.

Martin Grunenberg

Piano News 4/14 –

It is not the first time that the Hamburg-based Russian pianist Evgeni Koroliov has turned to Schubert. This time it is two of the great late sonatas. And already in the G-major Sonata D 894 he finds a balanced mode of expression that reveals the reflective pianist. With great calm and a feeling for the beautiful simplicity of the melodies, he shapes the expansive first movement, building the drama so skillfully that the listener is invited to follow Schubert’s train of thought. Yet Koroliov is such a seasoned interpreter that, despite all the inner tension, he not only maintains composure when the retarding moments appear, but also succeeds in presenting the large overall arc as a closed whole. Moreover, he makes clear that Schubert’s movements are always spun in an almost minimalist way from a single motif. Above all, Koroliov’s finely balanced sound production is captivating: always coherent, never affected, never turning ugly even in the fortissimo. Even in the Menuetto of the third movement, the Russian finds a distinctly Viennese tone of expression—perhaps taken just a touch too slowly. In general, one might imagine the tempi to be contrasted a little more strongly. Nevertheless, this does not detract from the playing, which is always marked by transparency. And the same qualities of a performance focused entirely on the music itself can be heard in the late A-major Sonata. With calm and the ability to listen to himself, Koroliov lets the music flow, shaping and forming it, acting as a pure interpreter. This is how Schubert should sound.

Carsten Dürer