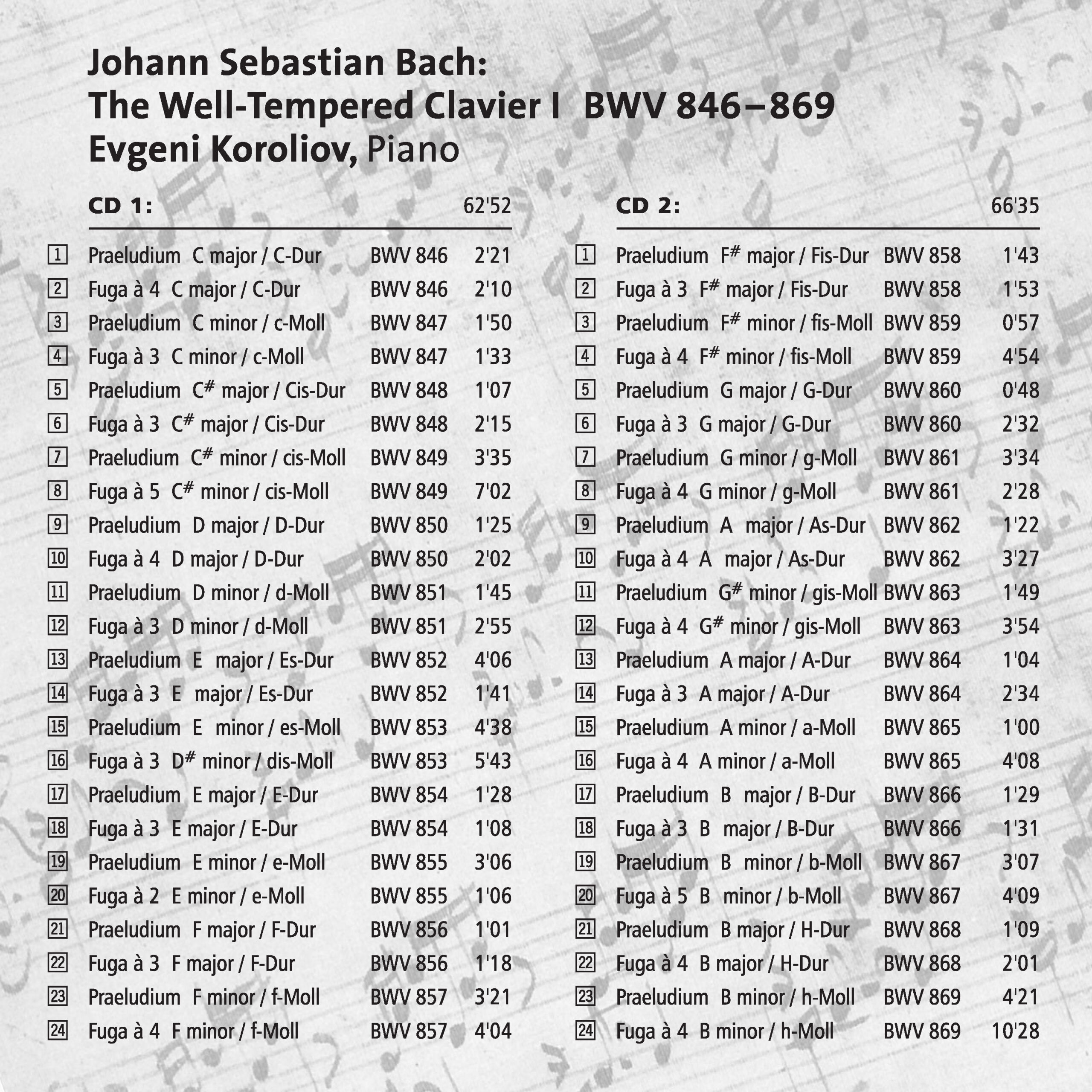

093 CD / Johann Sebastian Bach: Das wohltemperierte Klavier I

Description

"[...] Evgeni Koroliov can keep up with the genius of a Glenn Gould or the discovery of an ‘original sound interpretation’ – because he has something original to say, even though he does not deviate far from the familiar paths. This does not mean that there is nothing new to be learned from his Bach interpretations. [...] Koroliov finds his own colour for each piece entrusted to him, fanned out between archaically robust grasping [...] and an elegantly refined piano sound [...]. But he makes the most lasting impression where he digs deepest: in calmly sounding the depths of, for example, the great minor fugues, where, forgetting himself entirely, he unearths the really essential part of this music." (Süddeutsche Zeitung)

17 reviews for 093 CD / Johann Sebastian Bach: Das wohltemperierte Klavier I

You must be logged in to post a review.

hifi & records –

Evgeny Koroliov (…) allows this great music to speak for itself, never getting in its way. By the second prelude, one forgets the musician entirely and is drawn into the wondrous intricacies of the art. This ascetic interpretation focuses so intently on the music that listening becomes a meditative exercise. This is explicitly a good thing, as this work is far too precious for casual consumption and deserves the listener’s undivided attention. Altering the musical text is unthinkable for Koroliov, and he dismantles the arguments of other pianists—who claim that voices in dense fugues must occasionally be octave-transposed for clarity—with his flawless, never self-indulgent technique. With him, everything is always audible, suggesting that those other soloists simply need to practice a bit more. (…)

Stefan Gawlick

Die Zeit –

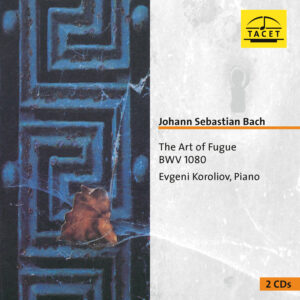

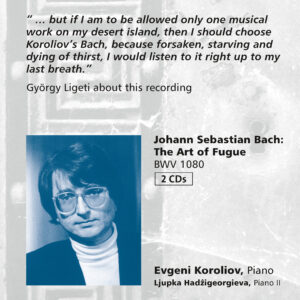

One could have honored Evgeny Koroliov as a significant Bach interpreter a full decade ago. In 1990, a small Stuttgart label released Bach’s The Art of Fugue, performed by a virtually unknown Russian pianist. For György Ligeti, this was the desert island disc. The composer was so convinced by Koroliov’s Bach that he declared he would listen to it, "abandoned, starving, and thirsty, until his last breath." High praise indeed. Yet it would be difficult to claim that this truly fascinating recording—which was fortunately reissued last year—ever received anything close to the recognition it deserved.

Today, Evgeni Koroliov is fifty years old and remains a largely unknown figure. The Bach Year should change that—anniversaries can, after all, have their merits. Bach and Koroliov share a relationship that spans nearly a lifetime. At just seventeen, he performed The Well-Tempered Clavier in his hometown of Moscow, possibly influenced by the legendary pianist and great Bach interpreter Maria Judina, who was revered in the Soviet Union like a living myth. She occasionally gave the young pianist free lessons, as did her colleague Heinrich Neuhaus, the second great Russian piano legend after the war. Koroliov thus embodies a grand tradition, one he now passes on not in Moscow or St. Petersburg, but as a professor at the Hamburg University of Music and Theatre. A topsy-turvy world, indeed. Koroliov is a master of tonal colors, capable of evoking the chamber-music transcendence of a trio sonata just as vividly as the thunderous swell of a fully registered organ. His interpretation of The Art of Fugue sounds like a joyful refutation of the idea that Bach’s late work is purely speculative. It oscillates between contemplative introspection and exuberant vitality, between otherworldly immersion and dazzling virtuosity. Even in the most rigid counterpoint, Bach remains, for Koroliov, a great melodist. And in some of the slow minor-key preludes and fugues of The Well-Tempered Clavier, he even brushes against a Romantic tone, tentatively searching for that unbounded sound that hints Bach may have subtly touched on ultimate things here. Thus, Koroliov becomes both analyst and mystic in one. With a rounded piano tone, he achieves the phenomenal clarity of counterpoint that Friedrich Gulda also attained in his groundbreaking 1972 recording of The Well-Tempered Clavier, with its glassy, almost harpsichord-like sound. Yet Koroliov also evokes, like a distant echo, the poetry that Edwin Fischer brought to his Bach interpretations in the 1930s. Bach on the piano—a long history. Fischer, Gould, and Gulda are just a few of its giants. But the story is still open. Koroliov’s Bach makes that clear once again after years of relative silence. And György Ligeti might find that a single CD on that deserted island won’t be enough after all.

Oswald Beaujean

image hifi –

In every moment of his recording of The Well-Tempered Clavier, one gets the impression: Here is someone who, over thirty years of interpretive experience, has cultivated a profound understanding of the work. Perhaps it does mean something when a pianist first performs The Well-Tempered Clavier in public at the age of seventeen and has been unable to let go of it ever since. Experience and knowledge are one thing; translating them into sound is another. Koroliov’s two hands weave three-, four-, and five-part fugues from perfectly shaped individual voices into a seamless whole—no seams visible, just a perfect garment of individual parts in various, wonderfully harmonious, intimately luminous colors. It is piano playing in the golden ratio—a trinity of textual precision, individuality, and soul. If there are any points of reference for the perfection offered on TACET 93, they might be found in Claudio Arrau’s finest recordings and in other repertoire. Arrau, too, channeled his extraordinary skill into piano playing that wasn’t about being “faster,” but about masterfully shaping every detail and the whole.

After all, this is one of the finest piano recordings in terms of sound quality across all formats—but does that really matter to you?

Heinz Gelking

Klassik heute –

The seriousness, meticulous care, and depth of Evgeni Koroliov’s interpretations promise this new recording a bright future—even in the face of stiff competition.

Peter Schlüer

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

There is something mystical about this piano playing(...) Little here is predictable: This is no technocrat at the keys, but a mystic. Granted, one who can articulate with the same irresistible clarity as Glenn Gould, while commanding a palette of tonal colors as rich as Alfred Brendel’s. Truly, a veritable cosmos unfolds before us.

fab

Fono Forum –

THE KOROLIOV-YEAR...

Werner M. Grimmel –

In analytical clarity, transparency of sound in fugal passages, cantabile phrasing, rhythmic drive, and vibrant vitality, this recording even surpasses Friedrich Gulda’s groundbreaking 1972 interpretation. Koroliov possesses not only an eminent touch but also an interpretive depth that makes his flawless Bach playing sound both spiritually elevated and sensually rich. The technically exemplary production, complemented by Christoph Ullrich’s original and poetic liner notes, once again establishes the now fifty-year-old pianist as one of the most significant Bach interpreters of our time.

Werner M. Grimmel

NWZ –

For the Desert Island

And lastly, absolutely top-tier: the pianist Evgeni Koroliov, who is also masterfully represented multiple times in Hänssler’s major edition, with The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I and The Art of Fugue (each 2 CDs on TACET). The composer György Ligeti would take these recordings with him to the oft-cited desert island and, "starving and thirsty in solitude, listen to them again and again until his last breath..."

Hanns-Horst Bauer

WDR –

… The Well-Tempered Clavier is more than just a self-contained, pedagogical work revolving around itself. In Koroliov’s hands, it becomes a kaleidoscope of music history and its interpretive possibilities…

Michael Krügerke

Bayerischer Rundfunk –

… Since Edwin Fischer’s fascinating—if now, in its romanticized approach, no longer feasible—1930s recording, a number of excellent, even phenomenal complete recordings of The Well-Tempered Clavier have emerged on piano, with Glenn Gould and Friedrich Gulda being just two notable examples. Koroliov seamlessly continues this great interpretive tradition, yet with a distinctly individual approach: On one hand, he focuses on crystal-clear lines and structures, examining Bach as if under the analyst’s magnifying glass; on the other, he simultaneously allows room for a decidedly romantic sensibility—for me, an ideal blend of heart and mind. It is high time Koroliov is finally recognized as one of the great Bach interpreters—and indeed as one of the most significant pianists of our time. His name remains unjustly and regrettably underappreciated. This fantastic recording is available on TACET.

Oswald Beaujean

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

A fixed star shines by itself.

Unaffected by the day's excitements, Evgeni Koroliov follows his own path. He is not a star in the pianist firmament as far as the media are concerned, but to those who have heard him and appreciate his recordings, he appears in his quiet greatness as a fixed star — a very distant, self-luminous celestial body that seems firmly anchored above, yet in reality slowly changes its position.

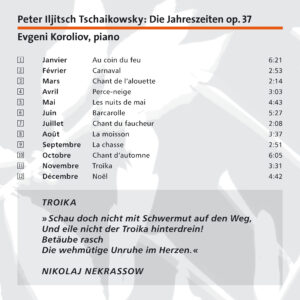

Koroliov is no showman and doesn’t play in the league of self-promoters — someone like him is hard to market. As someone who makes little fuss about himself or his abilities, he was fortunate to encounter the right producer and sound engineer. None of the industry’s big moguls wanted to bring him on board — it was a stroke of luck that he met Andreas Spreer, founder of the Stuttgart-based Tacet label and a meticulous craftsman at the microphone. Spreer is committed to the aesthetics of unadulterated sound. Nothing is glossed over or manipulated in any way. His recordings remain excellent and incomparable, especially the Prokofiev interpretations (“Visions fugitives” Op. 22, “Sarcasms” Op. 17, and Sonata No. 5 Op. 38, Tacet 32), as well as the Schubert CD featuring the great B-flat major sonata and the Moments Musicaux (D 780, Tacet 46), shaped entirely from the music’s closeness to death. Also remarkable is his rendition of Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons (Tacet 25), a cycle not easily accessible to everyone and rarely recorded.

And Bach, of course. Bach is the central sun in the life of pianist and piano professor Evgeni Koroliov (53), who lives in Hamburg. The Art of Fugue (Tacet 13) — one of the most intriguingly enigmatic works in the history of music in the best sense. Now, after years of hesitation and doubt, he has completed the recording of all 48 Preludes and Fugues of The Well-Tempered Clavier with the release of the second volume (Tacet 93 and 104). Live recordings from concerts of the International Bach Academy Stuttgart, released on Haussier Classics, include the Goldberg Variations as well as two additional Bach CDs.

His Bach playing strikes a balance between intellect and emotion; it leans into the melody while delivering powerful, chordal accents. A fiery spirit turns inward in reflection. Koroliov doesn’t smooth out the edges — he remains sharply alert. In doing so, he distances himself as much from the subtly romanticized interpretations of Sviatoslav Richter as from the unorthodox exegesis of Glenn Gould. (…)

Jürgen Holwein

International Record Review –

... Like other distinguished Bach pianists past and present, Koroliov proves beyond a shadow of a doubt that this music is not merely plausible on the concert grand, but benefits from the instrument′s capacity for varied colours, dynamics and articulations. - Indeed, this set′s most striking quality lies in the way Koroliov makes each prelude and fugue so unapologetically pianistic, while largely avoiding stylistic incongruities. His tone may lack Sviatoslav Richter′s extraordinary prismatic sheen, yet it is firmly centred from top to bottom. -

Moreover, Koroliov eschews Richter′s liberal use uf the sustaining pedal and obtains nuanced continuity in, say, the opening four preludes by fingerwork and hand balance alone. While he is not as adventurous as András Schiff or Sergei Schepkin in his ornamentation, his vibrancy taps into a dimension beyond Glenn Gould′s X-ray deconstructions or Rosalyn Tureck′s overtly worked-out voice leadings...

TACET′s excellent engineering draws you into Koroliov′s formidable artistry...

Jed Distler

Classics Today –

Reference Recording - "This one"

RATING: PERFORMANCE: 10 / SOUND QUALITY: 10

Evgeni Koroliov′s recordings of The Art of Fugue (for Tacet) and the Goldberg Variations (for Hänssler) have placed him in the forefront of today′s Bach pianists. This new recording of Book One of the Well-Tempered Clavier confirms his stature in this repertoire beyond a shadow of a doubt. Koroliov plays this music with such poetry, finesse, and real joy that questions of "authenticity" or instrument selection fade into insignificance.

In his title for the work, Bach deliberately avoided naming a specific keyboard instrument, and it′s known that this music could and would certainly have been played on everything from a harpsichord to clavichord, organ, or even early piano. In fact, Bach′s music is a celebration of keyboard virtuosity, and Koroliov′s performance offers a genuine display of the pianist′s art. His playing of the G major fugue, for example, has the brittle clarity of the harpsichord but a witty brilliance that is all his own. On the other hand, the mesmerizing, gradual crescendo and diminuendo he makes of the long C-sharp major fugue offers a textbook lesson in how to use the piano′s dynamic shadings to enhance the clarity and harmonic tension of Bach′s contrapuntal lines. Even the more familiar fugues--the two openers, for example, in C major and minor--sound refreshingly vital and interesting, owing to a combination of irresistible forward momentum and a really intelligent, ear-catching approach to voice leading.

Koroliov′s view of the preludes is no less impressive: he perfectly catches the subdued, elegiac quality of the pieces in G minor and G-sharp minor. His playing has all the gentle intimacy of the clavichord. On the other hand, he′s not afraid to attack the F-sharp minor prelude with real anger and an almost Lisztian bravura, and he can stroke the simple, arpeggio preludes (such as the very first, in C major) with a dreamy sensuality that has us confused as to whether we are listening to Chopin or Bach, and frankly not caring which. In sum, this is a performance worthy to stand beside Gould, Tureck, Schiff, Fischer, or any other competing version that you can name. And it′s better recorded than any of them. The only drawback: really pretentious booklet notes that, as so often with German productions, say nothing intelligent about the music at all, and exist solely to prove that the note writer thinks he′s smarter than the composer. Who is he kidding? Never mind. Bring on Book Two!

David Hurwitz

Classica –

Robert Levin’s choice wins us over with its originality: performing each of the twenty-four Preludes and Fugues from the First Book of The Well-Tempered Clavier on the instrument he believes best suits their character—single- or double-manual harpsichord, organ, or clavichord. Didn’t André Isoir recently declare in Classica that Bach, master of all keyboard instruments of his time, likely envisioned instruments other than the harpsichord for certain pieces in this collection? The real appeal of Levin’s version lies in this instrumental variety and its fine execution. Some choices may invite debate, but the interpreter always defends them with conviction.

As for Evgeni Koroliov, he moves us once again by remaining true to his beautiful piano, with its exquisitely refined sound. The works seem to call for no instrument but the piano. Koroliov, however, avoids presenting the diptychs as a grand cycle (as Glenn Gould does, to some extent), instead playing with mastery and intelligence, highlighting the lyrical poetry of each piece without lingering. The Fugues, often taken at rather slow tempos, emphasize the interplay and dialogue between voices more than the linearity of the polyphony. Combining certain motoric aspects of Gould’s approach with a more subjective, sensitive touch, this superb version stands alongside the Canadian pianist’s legendary recording—unmatched in polyphonic clarity (and swing, which can sometimes grate)—while no other fine rendition by Fischer, Gulda, or Tureck enjoys comparable recording quality. Koroliov thus emerges as a genuine alternative to Gould’s dominance.

Stéphan Vincent-Lancrin

______________________________________

Original Review in French language:

Le choix de Robert Levin séduit par son originalité: jouer chacun des vingt-quatre Préludes et Fugues du Premier Livre du Clavier bien tempéré sur l′instrument qui, à son sens, sied le mieux à leur caractère: clavecin à un ou deux claviers, orgue, clavicorde. André Isoir ne déclarait-it pas récemment dans Classica que Bach, maître de tous les instruments à clavier de son époque, désirait sans doute un autre instruments que le clavecin dans certains pièces de recueil? Tout l′intérèt de la version de Levine vient de cette variété instrumentale et de belles réalisations. Certains choix peuvent prêter à discussion, mais l′interprète les defends toujours avec conviction. Quant à Evgeni Koroliov, il nous touche une fois encore en restant fidèle à son beau piano à la sonorité si fine. Les oeuvres ne semblent alors pas appeler d′autre instrument que le piano. Koroliov tente cependant de singulariser les diptyques, en résistant à la tentative de les présenter comme un grand cycle (comme le fait Glenn Gould, dans une certaine mesure), il joue avec maîtrise et intelligence, soulignant la poésie lyrique de chaque pièce, sans pourtant s′y appesantir. Les Fugues, prise dans des tempi souvent assez lents, éclairent moins la linéarité de la polyphonie qu′elles ne jouent sur les réponses et dialogues entre voix. Alliant certains aspects motoriques de la vision de Glenn Gould à un jeu plus subjectiv, plus sensible, cette très belle version rejoint au sommet de la discographie celle du pianiste canadien, imbattable du point de vue de la clarté polyphonic (et du swing, lequel peut gèner) – aucune des belles versions de Fischer, Gulda ou Tureck ne bénéficiant d′une qualité d′enregistrement comparable. Koroliov devient ainsi une véritable alternative à l′hégémonie gouldienne.

Stéphan Vincent-Lancain

Répertoire –

The selection of the finest recordings – Another remarkable achievement by the German sound engineer Andreas Spreer, who presents us here, in particularly warm sound, with a dream piano. The recording is flawless, as it delivers the instrument in its entirety and homogeneity just a few steps behind the speakers. The reproduction is life-sized, both in width and height. The subtleties of touch and string vibration are conveyed in their fullness and completeness. A sonic masterpiece.

_______________________________________

Original Review in French language:

La sélection des meilleures prises de son – Une nouvelle prouesse de l′ingénieur du son allemand Andreas Spreer, qui nous détaille ici, dans un son particulièrement chaleureux, un piano de rêve. L′enregistrement est parfait, car il nous livre l′instrument dans son ensemble et son homogénéité à quelques pas derrière les enceintes. La restitution est à dimension réelle, tant en largeur qu′en hauteur. Les subtilités du toucher et de la vibration des cordes nous sont transmises dans leur intégralité et plénitude. Un chef-d′oeuvre sonore.

Le monde de la musique –

... After such a treasure trove of invention and generosity, the interpretations by Gould, Gulda, and Nikolaeva seem far more predictable and unambiguous. As poetic as Edwin Fischer, yet more rigorous, Koroliov delivers one of the most moving and radiant versions of this First Booklet.

Philippe Venturini

___________________________________________

Original Review in French language:

… Après un tel trésor d′invention et de générosité, les interprétations de Gould, Gulda et Nikolaiewa semblent bien plus prévisible et univoques. Poétique comme Edwin Fischer, mais plus rigoureux, Koroliov offre une des plus émouvantes et rayonnantes versions de ce Premier Cahier.

Philippe Venturin

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

Extravagant in Avoidance

Evgeni Koroliov Plays Bach Like No Other

No pianist sits at the keyboard with less ostentation. His upper body, his arms, the way he holds his head (you can picture the piano geniuses tilting their heads back, gazing into the infinite expanse of the concert hall to glimpse the divine)—his expressions reveal nothing of what transpires within him. If he suffers, he does not let us share in it. On the world’s piano stages, self-dramatization is commonplace. Even modesty can be staged. For Evgeni Koroliov, now 50, it is not. His hairstyle harks back to the 1970s. In 1976, he relocated from Moscow to Yugoslavia. Two years later, at 29, he accepted a professorship at Hamburg’s University of Music. Even the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow, where he had just completed his studies, invited him to teach. By the time he arrived in Hamburg, he had already won prizes at several competitions. He wears large glasses, the kind associated with a well-read man. He could be a senior librarian or a watchmaker, someone accustomed to dismantling a piece into its smallest components and reassembling it into a perfect whole. Koroliov is a master in his workshop, not an artist in the salon. Least of all does he fit the myth of the virtuoso pianist—though, when necessary, the spirit of a piano titan can possess him, turning his hands into powerful claws. Today, a piano professor neither young nor old, he performs concerts at home and abroad. Above all in Bach—though not exclusively—he has much to say. His reputation is not built on spectacle, and thus he does not conform to the marketing world’s image of what a recording artist should be. His first CD did not appear until 1990, fittingly featuring one of Bach’s most enigmatic works, The Art of Fugue—for Koroliov, an exercise in isolation. Not with an international label, but as the 13th release from Tacet (then a small, barely known Stuttgart-based company). Composer György Ligeti once said he would take Koroliov’s Bach to the proverbial desert island, "for I would listen to this record, starving and thirsty in solitude, again and again until my last breath." Two years later, Koroliov returned to the studio to record Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons (Tacet 25). He played Prokofiev’s Sarcasms and some Visions fugitives (Tacet 32), infusing them with percussive energy and creating moments of steely brilliance. In 1995, Schubert’s Sonata in B-flat Major and Moments musicaux, Op. 94 (Tacet 46) followed.

Koroliov can wait. Even Andreas Spreer, Koroliov’s devoted fan and producer, couldn’t persuade him for years to disappear into the studio with The Well-Tempered Clavier—despite the fact that Koroliov had already performed the entire cycle at 17 in Moscow. Now, Part One is here (Tacet 93), with Part Two planned.

The Bach Year has given the reticent Koroliov a push. In Hänssler’s Bachakademie edition, his Goldberg Variations (Vol. 112) have been released, preceded by the Inventions and Sinfonias (Vol. 106), the second part of the Clavier-Übung, and the Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, BWV 903 (Vol. 108). Koroliov embodies the incarnation of a model student carrying within him a far-from-glamorous childhood. He is sparing with the pedal, extravagant only in avoiding luxurious states. He demonstrates the absolute simultaneity of two independent hands—the first prerequisite for playing Bach. His Bach playing forges its own path between swing and romanticism, between Gulda and Sviatoslav Richter. Whoever plays Bach like this serves not distraction, but concentration. Beyond technical questions, it is essentially a matter of thought. But how does he play Liszt?

Jürgen Holwein