104 CD / Johann Sebastian Bach: Das Wohltemperierte Klavier II

Description

"You cross the Place de L′Alma, the city lights, the Paris bustle and enter the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées with those mundane trivial conversations. You find your seat and the audience takes its time quietening down. Evgeni Koroliov appears on the scene, gives a quick greeting and places his hands on the piano... And voilà, you are instantly transported to another world ..." (Le Figaro)

14 reviews for 104 CD / Johann Sebastian Bach: Das Wohltemperierte Klavier II

You must be logged in to post a review.

Crescendo –

Rather free in his handling of the written score—particularly in tempo and ornamentation—Evgeni Koroliov plays The Well-Tempered Clavier with a knack for making everything sound utterly plausible and effortless. With an ever-flowing touch and a lightness of articulation, he often makes the music’s complexity fade into the background. His interpretation is further enhanced by the excellently recorded, intimately resonant piano. "Only when one fails to identify with the music does something like an 'interpretation' emerge—an interpretation as misunderstanding," Koroliov writes in the booklet. That he identifies deeply with this music is audible in every single note.

KH

Répertoire Nº 169 –

After his recording of The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I (Répertoire No. 136, rated 8), Russian pianist Evgeni Koroliov—now based in Germany—confirms with this performance of Book II his interpretive choices and absolute mastery of this most complex corpus. Perfectly serene, these readings reveal, as if in an open book, the treasures of invention in the Preludes as well as the contrapuntal sorcery of the Fugues.

Koroliov’s touch, of constant beauty and density, ensures a flawless unfolding of the voices, never resorting to the slightest effect in articulation or intonation—unlike Glenn Gould in the past, or Olli Mustonen today—and instead recalls the richness of Tatiana Nikolaeva’s recordings. The pianist adopts the style of playing—staccato, louré, legato—that best suits the character he assigns to each piece, always maintaining the clearest intelligibility of the voices within a carefully defined dynamic range from pianissimo to forte. Rather than emphasizing expressive moments within the pieces, he chooses to characterize each piece in the totality of its progression.

The relationships between Prelude and Fugue appear so thoughtfully constructed that they seem to fall into two categories: those allowing a shared approach to the Prelude and Fugue (No. 5: clarity and bounce; No. 9: delicacy and stability; No. 10: lightness and tension; No. 15: wonderful chatter; No. 16: authority and declamation; No. 19: calm simplicity; No. 21: luminous serenity), and those where the relationship is marked by contrast between the Prelude and Fugue (No. 1: fullness/tonicity; No. 2: strength and precision/serenity; No. 14: breadth of breath/assertion; No. 17: intensity and seriousness/playful spirit; No. 23: carefree lightness/calm breadth).

Beyond this particularly coherent approach, some of the most enthusiastically expressive successes stand out: No. 3, with its magnificent swaying over the arpeggiated chords of the Prelude and the momentum in the overlapping voices of the Fugue; No. 18, with the clarity and forward motion of the Prelude followed by the intimate confidence of the Fugue; No. 20, for the mysterious restraint of the Prelude and the ornamented articulation of the Fugue; No. 22, with the tight weave in the calm of the Prelude and the tension of the Fugue, maintained all the way to the grand final stretto; No. 24, with the unpredictable progression of the discourse in the Prelude—sometimes detached, sometimes measured—and the exuberant yet perfectly stable outburst of the Fugue.

More so than with their predecessors in Book I—perhaps less refined in substance—these Preludes and Fugues of Book II provide Evgeni Koroliov with the opportunity to demonstrate his intimate understanding of these texts, their construction, and their harmonic progressions.

Gérard Honoré

___________________________________________

Original Review in French language:

Après son Livre I du Clavier bien tempéré (Répertoire Nº136, note 8), Evgeni Koroliov, pianiste russe aujourd′hui établi en Allemagne, confirme avec cette exécution du Livre II ses options interprétatives et son absolue maîtrise de ce si complexe corpus. Parfaitement sereines, ces lectures laissent se dévoiler comme à livre ouvert les trésors d′invention des Préludes tout comme les sortilèges contrapuntiques des Fugues. Le toucher de Koroliov, d′une constante beauté et densité, assure un parfait déroulement des voix, sans jamais recourir au moindre effet ni dans l′articulation ni dans l′intonation, à la différence de Glenn Gould hier, et par exemple d′Olli Mustonen aujourd′hui, et rappelle plutôt la plénitude des enregistrements de Tatiana Nikolaeva. Le pianiste adopte le style de jeu – staccato, louré, legato… – le plus conforme au caractère qu′il choisit de donner à chaque pièce, en conservant toujours la meilleure intelligibilité entre les voix, dans une plage de nuances soigneusement fixée du pianissimo au forte. Plutôt que l′opter, au sein des pièces, pour un soulignement expressif selon les épisodes, il choisit de caractériser chaque pièce dans la totalité de son déroulement. Les rapports entre Prélude et Fugue paraissent d′ailleurs si construits qu′ils semblent pouvoir se classer en deux familles: ceux qui permettent une approche commune pour le Prélude et la Fugue (nº 5 netteté et rebond, nº 9 délicatesse et stabilité, nº 10 délié et tension, nº 15 merveilleux babillage, nº 16 autorité et déclamation, nº 19 calme simplicité, nº 21 lumineuse sérénité), et ceux pour lesquels ce rapport est marqué par le contraste entre le prélude et la fugue (nº 1 plénitude/tonicité, nº 2 force et précision/sérénité, nº 14 ampleur de la respiration/affirmation, nº 17 intensité et sérieux/esprit ludique, nº 23 délié insouciant/calme ampleur). Au-delà de cette approche particulièrement cohérente, il faut aussi souligner les plus enthousiasmantes réussites expressives: le nº 3, avec son magnifique balancement sur les accords arpégés du Prélude, et l′élan dans la superposition des voix de la Fugue; le nº 18 et la clarté et l′avancée du Prélude suivie de la confidence recueillie de la Fugue; le nº 20 pour la retenue mystérieuse du Prélude et l′énonciation ornée de la Fugue; le nº 22 avec le tissage serré dans le calme du Prélude et la tension de la Fugue, maitenue jusqu′à la grandiose strette finale; le nº 24, imprévisible progression du discours sur un rythme tantôt détaché, tantôt posé dans le Prélude, suivi du jaillissement foisonnant et parfaitement stable de la Fugue. Plus encore qu′avec leurs prédécesseurs du Livre I, à la matière sans doute moins élaborée, ces Préludes et Fugues du Livre II sont pour Evgeni Koroliov l′occasion de montrer sa compréhension intime de ces textes, de leur construction et de leurs progressions harmoniques.

Gérard Honoré

KulturSPIEGEL –

On the Olympian Heights

Evgeni Koroliov, a purist by passion, has completed his Well-Tempered Clavier.

What could be so difficult about it? Why are these two sets of 24 short pieces—easily managed by piano students without contortions—such a mountain for virtuosos? Perhaps precisely because Johann Sebastian Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier is considered the Old Testament among connoisseurs: Here, no one can show off as an acrobat; everyone—including the listeners—is left alone with themselves and their own musicality. Countless musicians have attempted to decode the secret of this Baroque cosmos of keys, preludes, and fugues, and the number of recordings is legion. For this reason, among others, Evgeni Koroliov—who first performed the complete double cycle at the age of 17 in his hometown of Moscow—waited a very long time before entering the studio: Anyone aiming to compete with keyboard legends like Edwin Fischer, Wanda Landowska, Samuel Feinberg, Sviatoslav Richter, Rosalyn Tureck, Glenn Gould, and many others must bring something extraordinary to the table. Only now, at 53, did the unpretentious piano professor feel equal to the immense challenge. The result sounds flawless, far removed from any monument-worship, yet deeply expressive. With exemplary transparency—but never tinkling—Koroliov presents the sonic characters. For him, this Olympian work (especially the second part, with its, as Koroliov puts it, "richer fare") follows an almost casual "principle of diversity," ranging from graceful and sublime to witty or cozy. For this, he says, one doesn’t need an idiosyncratic interpreter, but simply a "player" who manages to "become one with the music." Easier said than done—but here, it has truly been achieved.

Johannes Saltzwedel

tz –

One of the most famous questions in the history of records and CDs—Which recording would you take to a desert island?—was answered by one of the great composers of our time, György Ligeti, as follows: "I would choose Koroliov’s Bach, because even starving and dying of thirst in solitude, I would listen to this record again and again until my last breath."

Well, you don’t actually have to starve or die of thirst—but one thing we can guarantee: Koroliov’s Bach playing is addictive. Now, the Russian pianist, a professor at Hamburg’s University of Music, has recorded the second volume of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier. Just another recording? No. Perhaps the recording.

Koroliov possesses all the virtues needed to make this complex music bloom in full. There’s not a trace of vanity or eccentricity (unlike, forgive me, Glenn Gould’s Bach, where it so often creeps in). Here, the contrapuntal interweavings grow organically from the theme. Heavenly, the incredibly diverse, branching, yet always firmly rooted textures that emerge!

His playing is extremely precise and controlled, but never cold. One always senses immense intellect and artistic will—never forced, never artificial. We know of no other recording where each individual voice carries such weight, sounding so independent and sublime. Can instrumental music be political, even in the Baroque era? In this case, yes. Because the way Koroliov handles the individual voices—this is democracy in action.

Matthias Bieber

NWMagazin –

On quiet soles, Evgeni Koroliov conquers concert halls. Those who have heard him once remember him above all for his Bach playing—for its intensity, its intellectually rigorous yet emotionally dense portrayal of Bach’s cosmic universe. In the 48 pieces of the second volume, Koroliov—a professor at Hamburg’s University of Music—demonstrates that with this part of the "Old Testament of piano playing" (as Hans von Bülow called it), Bach achieved a significantly higher degree of complexity than in the first compendium. This doesn’t refer (just) to the contrapuntal mastery—always the ne plus ultra in Bach’s works—but to the refinement of each piece’s distinct character. And if the listener yields to Koroliov—something this great pianist not only permits but suggestively compels—then the genius of this musical cosmos becomes undeniable. It’s as if body, soul, and mind were in perfect balance. Yet all Bach intended was to write practical exercises for "eager young learners"!

Brilliant

bri.

Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung –

For aspiring pianists, Johann Sebastian Bach’s twofold keyboard journey through all major and minor keys—composed as preludes and fugues—is an absolute must. The reverence for this cycle once led Hans von Bülow to call The Well-Tempered Clavier the "Old Testament of piano music." Its interpreters approach Bach’s tonal odyssey with varying attitudes—some with devotion, others, like the late Glenn Gould, with extravagance. For Evgeni Koroliov, who—after many discographic Bach explorations—has now recorded the second part of The Well-Tempered Clavier, the transmitted musical text is paramount. Yet the pianist, born in Moscow in 1949 and teaching in Hamburg since 1978, does far more than play with mere accuracy and precision. He colors each prelude according to the character dictated by its key and shapes the polyphonic weave of every fugue with tireless, exemplary joy.

The result is anything but academic or merely museum-like. Koroliov brings this venerable work to life. He is neither self-indulgent nor given to superficial virtuosity. Instead, he presents himself as a first-rate advocate for Bach’s keyboard music—one whose sonically superb case for it thrives on knowledgeable engagement and deep-seated love. For Koroliov, body and soul are inseparable. His Bach playing unites intellect and emotion, and it is this very union that commands attention and inspires awe. His journey through Bach’s twelve major and twelve minor keys is an artistic stroke of fortune.

Ludolf Baucke

Fono Forum –

Symbiotisch

This double-CD confirms the interpreter’s outstanding reputation and his distinctly modern Bach style, marked by a rich interplay of analytical rigor and tender sensitivity. This elevates Koroliov’s Bach far above the often frustrating stylistics of pianists like Carl Seemann, who once cultivated a—then understandable—postwar objectivity as a counterpoint to the lingering remnants of Romantic Bach tradition. While artists like Edwin Fischer and Arthur Loesser delivered Bach with admirable artistry, though not without debatable diversity and depth, Koroliov’s approach is evolutionary and symbiotic—contrast-rich yet never excessive in its clarity. Here, one doesn’t feel overpowered, but engaged in dialogue.

RA

WDR, Hörproben –

…In the noise of our world, this music with this interpreter is a vanishing point…

…The depth of this Bach playing has something purifying. Its clarity, something unrelenting.

Michael Krügerke

Piano News –

After the release of Evgeni Koroliov’s interpretation of the first part of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier in the Bach Year 2000, the press overflowed with praise. Two years later, Koroliov now presents the second part—and, to cut to the chase, it is an equally compelling recording. Those hoping to discover something new, highly idiosyncratic, or different in Koroliov’s approach may be disappointed and should turn instead to the many recordings—especially by young interpreters—who use Bach as a vehicle for self-expression. Koroliov is an artist who always steps back behind the music itself, though with all his phenomenal skill. He possesses a subtle, refined touch capable of reflecting every nuance of Bach’s inventive genius. Moreover, he takes his time, allowing the music to unfold—a rarity today. In this way, the listener can truly absorb the playing and the music, hearing phrases they may never have noticed before.

Articulation is one of the most crucial elements in interpreting Bach’s keyboard music, and Koroliov seems to grasp it instinctively. His precise sforzandi, sharply defined shifts between forte and piano bring his playing to life. He also approaches the work with a true cyclical understanding—the flow created by these two CDs is almost irresistible. One can hardly stop listening to this brilliant Bach interpreter, again and again.

Even if you already own other great recordings of this work—such as Richter’s legendary version—this one deserves a place beside it.

Carsten Dürer

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

A fixed star shines by itself.

Unaffected by the day's excitements, Evgeni Koroliov follows his own path. He is not a star in the pianist firmament as far as the media are concerned, but to those who have heard him and appreciate his recordings, he appears in his quiet greatness as a fixed star — a very distant, self-luminous celestial body that seems firmly anchored above, yet in reality slowly changes its position.

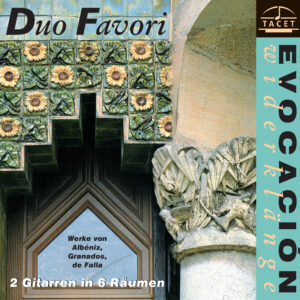

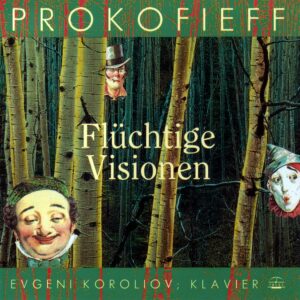

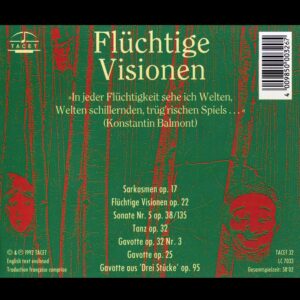

Koroliov is no showman and doesn’t play in the league of self-promoters — someone like him is hard to market. As someone who makes little fuss about himself or his abilities, he was fortunate to encounter the right producer and sound engineer. None of the industry’s big moguls wanted to bring him on board — it was a stroke of luck that he met Andreas Spreer, founder of the Stuttgart-based Tacet label and a meticulous craftsman at the microphone. Spreer is committed to the aesthetics of unadulterated sound. Nothing is glossed over or manipulated in any way. His recordings remain excellent and incomparable, especially the Prokofiev interpretations (“Visions fugitives” Op. 22, “Sarcasms” Op. 17, and Sonata No. 5 Op. 38, Tacet 32), as well as the Schubert CD featuring the great B-flat major sonata and the Moments Musicaux (D 780, Tacet 46), shaped entirely from the music’s closeness to death. Also remarkable is his rendition of Tchaikovsky’s The Seasons (Tacet 25), a cycle not easily accessible to everyone and rarely recorded.

And Bach, of course. Bach is the central sun in the life of pianist and piano professor Evgeni Koroliov (53), who lives in Hamburg. The Art of Fugue (Tacet 13) — one of the most intriguingly enigmatic works in the history of music in the best sense. Now, after years of hesitation and doubt, he has completed the recording of all 48 Preludes and Fugues of The Well-Tempered Clavier with the release of the second volume (Tacet 93 and 104). Live recordings from concerts of the International Bach Academy Stuttgart, released on Haussier Classics, include the Goldberg Variations as well as two additional Bach CDs.

His Bach playing strikes a balance between intellect and emotion; it leans into the melody while delivering powerful, chordal accents. A fiery spirit turns inward in reflection. Koroliov doesn’t smooth out the edges — he remains sharply alert. In doing so, he distances himself as much from the subtly romanticized interpretations of Sviatoslav Richter as from the unorthodox exegesis of Glenn Gould. (…)

Jürgen Holwein

Stuttgarter Nachrichten –

Long Ripened, Freshly Harvested

Without noisy fanfare, Russian pianist Evgeni Koroliov has, over nearly four decades, steadily ascended to the Olympian heights of the greatest Bach interpreters of all time. Even one of his earliest recordings—The Art of Fugue—prompted composer György Ligeti to declare: "If I could take only one work to a desert island, I would choose Koroliov’s Bach, for even starving and dying of thirst in solitude, I would listen to this record again and again until my last breath." Since performing Bach’s entire Well-Tempered Clavier at age seventeen, Koroliov has nurtured this project in his soul. Now, in his early fifties, he has completed the CD recording of this monumental cycle with the release of the second volume.

Once again, Koroliov demonstrates the ideal fusion of intellect and emotion—the hallmark of his unmistakable style. Though "demonstrates" is perhaps the wrong word. For Koroliov effaces himself entirely, making everything sound so natural, as if the music simply happens and he is merely listening along. By creating this impression—while still guiding each voice with sovereign control, giving every line conscious space to breathe, and never artificially highlighting a single phrase—he produces music that seems detached from muscle and sinew, yet brims with primordial power.

bri

image hifi –

When Evgeni Koroliov heard Glenn Gould’s Bach in a 1957 Moscow concert, he admired how every voice could be heard distinctly. Yet he also revered the "romantic" interpretations of Edwin Fischer. Despite such towering influences—and the historically informed performance movement, which distrusts the modern concert grand and would gladly claim J.S. Bach as its own—Koroliov has forged his own deeply personal vision of the old master. For this recording, Andreas Spreer captured the piano with unprecedented natural fidelity, while also giving the notoriously self-critical artist the time he needed to refine his interpretation. I previously introduced Koroliov’s recording of the first book of The Well-Tempered Clavier as part of Tacet’s label portrait. Now, with the second book (BWV 846–869), we are once again left in stunned awe at how he manages to combine absolute control with an inexplicable, soulful intensity. This is something far greater than Gould’s eccentricities.

hg

Classics Today –

Reference Redording: This one

As with his magnificent recording of Bach′s Well-Tempered Clavier Book 1, Evgeni Koroliov interprets Book 2 from a pianistic angle, taking advantage of the instrument′s potential for varied colors, articulations, and dynamics, while at the same time avoiding stylistic anachronisms. There are so many details to savor, you hardly know where to begin.

His unconventionally slow pace for the C minor fugue allows the contrapuntal lines to take on a more vocal quality than usual. Note how gorgeously he shapes the left hand′s often-ignored top line in the D-flat prelude and the subtle rubato with which he inflects the C-sharp minor fugue. In contrast to the D major prelude′s militant pomp, Koroliov takes an unusually brisk, nimble, and witty approach to its corresponding fugue (the A-flat fugue is similarly dispatched).

By contrast, Koroliov′s spacious, reverential way with the E major fugue recalls Glenn Gould′s similarly drawn-out mono recording. He resists Angela Hewitt′s dynamic contrivances in the difficult-to-clarify G minor fugue, achieving textural variety by means of his marvelously controlled staccato articulation. Koroliov keeps the G-sharp minor fugue′s lines afloat so that their accents fall over rather than on the barlines. The pianist′s gentle and introspective A minor prelude markedly contrasts to his bleak and hard-nosed way with its corresponding fugue.

What a joy it is to experience Koroliov′s authoritative and individual Bach pianism at its best. Don′t miss this release!

Jed Distler

Klassik heute –

…Koroliov doesn’t deliver a Bach that whips us into a frenzy or sends us climbing the barricades—instead, he immerses us in a state of serene calm and balance, making the world sound, for two hours, just a little better than it really is.

Peter Cossé