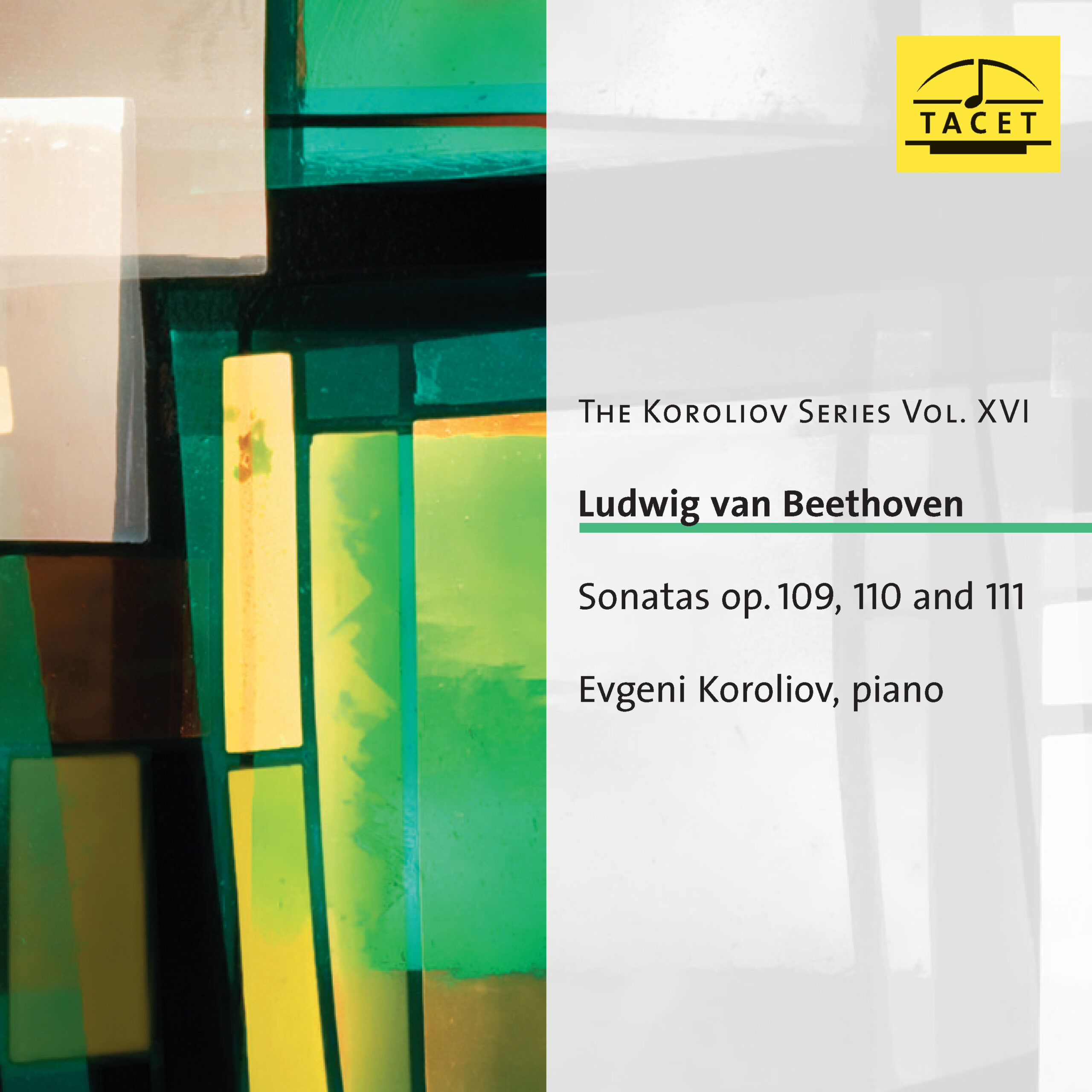

208 CD / Ludwig van Beethoven: Sonatas op. 109, 110 and 111

Description

Evgeni Koroliov, the master of nuance, announces himself again with another recording of the Late Piano Sonatas of Beethoven, this time with op.109, 110 and 111. A heavy, powerful touch is not his thing. Of course he plays loudly where it should be loud, yet he captures the listener in a different way. He seduces him with the beautiful sound of his touch and with an almost all-absorbing intensity, to engage in small and even minuscule agogic phrasing, slurs or accentuation, in the flow and tumble of the subtle beauty of the score, which often simultaneously develops its powerful undercurrent and yet urges us to grant it our awareness. Thus out of many endless, small treasures emerges an unimaginably beautiful and great whole.

Beethoven was not the powerful antagonist he is often portrayed as in loud but superficial interpretations. His creative force erupted in hieroglyphic ink blots on the paper; only in this way was he different to you and I. A mystery.

Beethoven war nicht der Kraftmeier, als der er in lauten, aber oberflächlichen Interpretationen oft hingestellt wird. Seine schöpferische Kraft entlud sich in hieroglyphischen Tintenklecksen auf Papier, nur darin anders als du und ich. Ein Mysterium.

11 reviews for 208 CD / Ludwig van Beethoven: Sonatas op. 109, 110 and 111

You must be logged in to post a review.

ConcertoNet –

--> original review

Evgeni Koroliov (born in 1949) turns Beethoven's Three Last Sonatas into expertly polished diamonds. While his previous Beethoven album (devoted to Opus 101 and 106) was more impeccably constructed than emotionally successful, the Russian pianist here breaks through the armor—and touches the heart. Opus 109, with rare coherence, flows like spring water, both personal and indisputable (despite the originality of the content). It unfolds unheard-of resonances. The stunning beauty of the twilight stillness and the methodical calm of certain passages culminate in a neutrality of tone that deeply confounds. Opus 110 follows a similar path. The personality of the discourse (sometimes quite perplexing, especially in tempo choices) asserts itself. The Adagio ma non troppo convinces that a great artist is at work. Opus 111 is more austere, as the singular, jerky, even painful rhythm disrupts in the first movement. However, one eventually surrenders to the logic of the whole, as Koroliov turns this Last Sonata into a Cubist manifesto that brings something new to the discographic structure of the work. A bewildering journey but a powerful experience.

Gilles d’Heyres

_______________________________________________________________________________

–> critique originale

Evgeni Koroliov (né en 1949) fait des Trois Dernières Sonates des diamants savamment polis. Alors que son précédent album beethovénien (consacré aux Opus 101 et 106) était plus impeccablement construit qu’émotionnellement réussi, le pianiste russe fend ici l’armure – et touche au cœur. D’une rare cohérence, l’Opus 109 coule comme de l’eau de source, à la fois personnel et incontestable (malgré l’originalité du propos). Il déploie des résonnances inouïes. D’une sidérante beauté par l’immobilité crépusculaire et le calme méthodique de certains passages, il s’achève dans une neutralité du ton qui déroute profondément. L’Opus 110 suit un parcours comparable. La personnalité du discours (assez déconcertant parfois, notamment dans les choix de tempos) s’impose d’elle-même. Et l’Adagio ma non troppo achève de convaincre qu’un immense artiste est à la manœuvre. L’Opus 111 est d’un abord plus aride, tant la rythmique singulière – heurtée, douloureuse même – perturbe dans le premier mouvement. Pourtant, on finit par rendre les armes face à la logique de l’ensemble, Koroliov faisant de cette Dernière Sonate un manifeste cubiste qui apporte quelque chose de neuf à l’édifice discographique de l’œuvre. Un voyage déroutant mais une expérience forte.

Gilles d’Heyres

American Record Guide –

--> original review

This Moscow-born pianist (1949) is now living in Germany. He was a student of Lev Oborin, Lev Naumov, and Maria Yudina. This is the third volume of his Beethoven sonata series and is sold at a premium price. The booklet shows him having already recorded a large amount of the repertory for his instrument. I have reviewed his Mozart, but have not been able to find a review of his earlier Beethoven recordings in ARG.

While one can give a bow to Koroliov’s credentials and to his digital control, whether he adds a special dimension to his playing worthy of attention is a question for the reviewer. Simply good is no longer enough when one is inundated with endless duplication—particularly of Beethoven’s last three sonatas.

I need not have feared. These are beautiful performances, played with generosity of vision, refined tonal allure when called for, powerful assertion and bursts of impressive speed when needed. Sonata 30 is played with all the refinement and sensitivity one could ask for. His hushed gentleness makes it seem that he really cares and has fully immersed himself in the music. Sonata 31 shares this gentle refinement. Late Beethoven need not present problems for the listener if performers have a grasp of the structures and clarify and balance the music effectively. Nowhere is this more evident than in the final Adagio and the Fugue that grows with steady inevitability, releases tension somewhat, only to again assault us with a briefly cryptic Allegro in closing.

Sonata 32 may be the most difficult for the average listener. It is in two movements. A final fugue was eventually rejected by the composer. Clarity, as an ever present factor in Koroliov’s interpretation, brings us closer to Beethoven’s thought processes as he allowed ideas to grow from in the seeds of what has preceded them. Still, the musings and final whimper at the close of the last movement may always leave one perplexed.

The sound of the Steinway D has been well caught by the engineers, and collectors should not hesitate to add this to their buy list of the last three sonatas. Obviously one cannot exist with just one performance of such glorious music.

© 2015 American Record Guide

Alan Becker

Fanfare Magazin –

--> original review

What is it about Beethoven’s last three piano sonatas that so fascinate us as both players and listeners? Is it the whole aspect of late style in general? The idea that his late statements are special in a way for the knowledge which they can impart both about the composer in specific and to humanity in general? Are they more personal in nature? Perhaps all of these. But perhaps it is more so because these works show Beethoven as a great stylistic compiler. Here Beethoven looked not to the burgeoning movement of Romanticism which surrounded him, but rather took inspiration from the past. These works then are to Beethoven what the Goldberg Variations, the second book of The Well-Tempered Clavier, or—perhaps more appropriately—The Art of Fugue is to Bach. These last sonatas show both history and its mirror through Beethoven’s lenses: The use of fugue, variation, moments of strict counterpoint balanced by prelude-like improvisation show the past; but there is also the contemporary in the use of genre, form, and the sense of balance, proportion, and Beethovenian growth towards an end goal.

Was diese Werke vor allem erfordern, ist ein Pianist, der all diese Qualitäten in den Vordergrund rücken kann, einer, der das Gefühl für die große Struktur mit den Schwierigkeiten ständig wechselnder komplexer Texturen, enormen Auf- und Abbau und sorgfältiger Beachtung musikalischer Details ausbalancieren kann. Evgeni Koroliov, der bereits einige der größten und komplexesten Werke dieser Zeit aufgenommen hat – die Goldberg-Variationen, Die Kunst der Fuge, das gesamte Wohltemperierte Klavier, die Diabelli-Variationen, den „Hammerklavier“ – besitzt diese Eigenschaften zweifellos in hohem Maße. Wie geht er also mit diesen komplexen Werken um?

The first words that come to mind regarding Koroliov’s approach include graceful, poised, and serene—words not normally associated with Beethoven. His approach takes much of the manic out of this music. This is a quality that is at times welcome, at times less so. But the more I’ve listened to it, the more I’ve become convinced—even entranced—by it. Take the opening of the E-Major Sonata, op. 109. Koroliov takes his time, spinning each note of the opening arpeggiation with a careful attention to matters of voicing and pacing: In his hands, the broken chords betray the work’s true identity—a hymn. The second theme sounds almost like the improvisations of a church organist. The highlight of this performance comes in the last movement, though. There is a sense of evolution from the beginning of the movement to the end, each variation gliding seamlessly from one to the next. A particular highlight is the fugal variation: In some hands this can become a mechanical exercise, but in Koroliov’s the slight breaths between phrases heighten rather than lessen the contrapuntal interplay.

Koroliov’s A♭-Major Sonata No. 31, op. 110, is equally mesmerizing. As in No. 30, the work begins calmly. Even the A♭arpeggios which cascade up and down the keyboard in the work’s first movement seem more like Baroque elaborations than Beethovenian swells. The second movement is particularly brisk and relentless in the energy the pianist brings to it. The finale is again the highlight for numerous reasons: the way in which the pianist beautifully contrasts the singing fugue, with the more speech-like arioso and recitative sections; the way in which he links these disparate strands of music together, creating a great aural tapestry which all seems to be woven right before us; and not least of all, for the momentum which he forges from beginning to end. In Koroliov’s hands the whole Sonata feels as one continuous movement of music—a massive dramatic suite of sorts.

Though Koroliov may lack dynamic punch in certain instances, his sound is always beautifully rounded and he always maintains a vivid tonal sheen in even the largest and thickest of chords—an aspect of his playing which helps with the massive sonorities of the final C-Minor Sonata. Though op. 111’s first movement is well played, it is a bit too muted in tone for my taste. Everything just sounds too rounded, too perfect—too nice. But the following variations restore one’s faith in Koroliov’s approach. Here he lets loose his magic: The pace is slow, as is the buildup, the accents hushed; the overall feeling at the work’s conclusion is one of inevitability.

I could hardly live without my other recordings of these works—be it the eccentric Glenn Gould, the driven Rudolf Serkin, the grand Myra Hess, the suave Edwin Fischer, the dynamic Sviatoslav Richter, or the polished and brilliant Maurizio Pollini. There are simply too many ways to approach these works for one way to ever be enough. But if you have room in your collection for yet another—and if you don’t I recommend you make some—this is one of the most individual realizations I’ve come across in some time. The magic of Koroliov’s music-making lies in his ability to take the eccentric out of these works: He makes these final essays seem as the next logical step in the composer’s evolution, not the strange and peculiar ramblings of a deaf madman who could only find inspiration from deep within himself. Rather, Koroliov brings out in these compositions the Beethoven of the Ninth Symphony—the composer who sought to embrace everything he knew and cherished in the world. Koroliov’s Beethoven may be muted in some instances, perhaps a bit more subtle than some like, but I can assure you, at its best, his is also highly captivating.

Scott Noriega

Stereo –

Audiophiles Highlight des Monats

Schon die erste Beethoven-Aufnahme Evgeni Koroliovs mit dem A-Dur-Werk op. 101 und der „Hammerklaviersonate“ rage aus der Masse der jüngeren Einspielungen deutlich heraus. Kaum zwei Jahre später übertrifft sie dieser Volume XVI von TACETs „Koroliov Series“ jetzt womöglich noch an künstlerischer Stimmigkeit und Geschlossenheit.

The interpretations by the now 65-year-old Evgeni Koroliov, a choice Hamburg resident, achieved here strike me as literally unique in their combination of selfless dedication, purposeful concentration, and the finest sensitivity – an opinion that has not changed after I threw a generous dozen of older recordings by Schnabel and Kempff, Gulda and Gilels to Schiff, Korstick, and Uchida back into the player to confirm the strong initial impression. None of them appears to be so entirely free from declamatory superficiality, none interprets the text with such nuanced and delicate insight while remaining so simple and natural as he has succeeded in this production. Alone how Koroliov doesn't just stop the E-major sonata but lets it truly fade away through a slight delay of the final chord testifies to a superior and insightful mastery rarely documented before microphones.

Not insignificantly contributing to the lasting overall impression that this interpretative highlight leaves is TACET's recording technique, which has placed the instrument audibly well in space, once again in the time-tested Berlin-Dahlem Jesus Christ Church, without compromising the clarity of the sound with reverberation.

Ingo Harden, Stereo

www.kultur-port.de –

--> original review

Ein neuer Höhepunkt der „Koroliov Series“: Der Hamburger Pianist Evgeni Koroliov interpretiert die drei letzten Klaviersonaten von Ludwig van Beethoven – die CD führt einen eher stillen und gerade deshalb spektakulären Beethoven vor, neu befragt und ganz ohne Klischees.

The fact that Evgeni Koroliov is an interpreter of Bach of the highest, yet entirely unagitated elegance and brilliance, one who can play the counterpoint of the Thomaskantor on the piano with the clearest structural penetration, without losing sight of the soul of the music for even a second, is by no means only known to connoisseurs.

Dass der Hamburger Klavierprofessor, der 1949 in Moskau geboren wurde, in einem sehr viel breiteren Repertoire zuhause ist, ist weniger geläufig. Denn Koroliov entzieht sich konsequent jedwedem Rummel um seine Person und macht sich mit seinen Konzerten eher rar, obwohl ihm die großen Konzertpodien rund um den Globus offenstehen. Die Routine des Konzert- und Tourneebetriebs – Gott bewahre. „Die heutige Vermarktung von klassischer Musik würde ich als Künstler nicht überleben. Es entsteht da ein Sog, aus dem man nicht herauskommt. Es bliebe zu wenig Zeit und Kraft, sich weiterzuentwickeln.“

Wie gut, dass es da die „Koroliov Series“ des verdienstvollen Labels „Tacet“ gibt, auf deren CDs Koroliov neben den Großwerken Bachs auch mit Musik von Tschaikowsky, Debussy, Schubert, Prokofieff, Schumann und Chopin zu hören ist. Und eben mit Beethoven. Zuletzt erschienen: seine Aufnahme der letzten drei der 32 Beethoven-Klaviersonaten, op.109, 110 und 111. Formensprengende Werke, die Schlusspunkte in Beethovens Sonatenschaffen für Klavier, das gern auch als der „Neue Testament“ der Klavierliteratur bezeichnet wird, um ihm einen einzigartigen Rang neben dem „Alten Testament“ – Bachs „Wohltemperiertem Klavier“ zuzuschreiben. Mit blitzsauberer und kristallklarer Aufnahmetechnik festgehalten, die Koroliovs Steinway D direkt ins heimische Musikzimmer stellt.

What has already been read into these three sonatas – up to Beethoven's struggles with the cosmos, a colossal inner battle, and a purified letting go of the fighter. They can be played with storms and noble passions, even up to a blatant trilling transfiguration. Koroliov plays them differently.

Er gibt keine Richtung vor, in der man Beethovens Musik spielen und verstehen sollte. Er begleitet den Komponisten auf seiner Suche, die ja in vielen Brüchen immer wieder in diese Werke eingewoben ist. Fast so, wie Koroliov das auch zu Bachs Musik sagt: „Es geht nicht darum: Ist es melancholisch oder lustig, es hat eine ganz andere Dimension, ein Gefühl von innerer Harmonie, von Trost und – einzigartig, vielleicht klingt das zu hart – von Akzeptanz des Todes. Sie strahlt ein sehr tiefes Vertrauen aus.“

Koroliov invites us to participate in a polyphonic conversation.

The listener drifts with the pianist from thought to thought, reflective, sometimes contemplative. Koroliov allows us – and his Bach is a magnificent listening school for this – to participate in a polyphonic conversation where each individual expression is significant to him. When he builds up dark clouds, he soon allows small rays of sunshine to break through, he savors harmonies and melodies, lets them resonate. His playing is restrained and yet compelling, never relying on thunderous basses, excessively forced volume, or overt virtuosity. Koroliov relies on the power of deep penetration, which is often most audible and palpable when he plays very inwardly.

So wie im finalen dritten Satz der E-Dur-Sonate op. 109, einem langen, den „Goldberg-Variationen“ in ihrer Konsequenz sehr wesensverwandten Variationensatz, für den Beethoven vorschreibt „Gesangvoll, mit innigster Empfindung“. Nie lässt sich Koroliov in seinem zu vordergründigen Effekten verführen, sein Spiel quasselt den Zuhörer nicht voll, versucht ihn auch nicht zu überwältigen. Statt dessen pflegt er eine ausdrucksstarke Klangrede, in der ihm oft kleinste Veränderungen im Anschlag oder Tempo genügen, um die Ohren für die Seelentiefe von Beethovens Musik zu öffnen. Und seine Fähigkeit, die Spannung in gespannter Innigkeit über lange Bögen aufrecht zu erhalten.

So wie im dritten Satz, dem Adagio der As-Dur-Sonate op. 110, die die aus einem fast rezitativischen Adagio unvermittelt in eine große Fuge mündet. In der man deutlich die Vertrautheit mit den kompositorischen Ideen Bachs spürt. Mit denen war Beethoven – wie Jahre zuvor schon Mozart – bei den musikalischen Soireen des Barons van Swieten immer wieder in Berührung gekommen und sie hatten größten Eindruck auf ihn gemacht, der gut in seinem respektvollen Bonmot „Nicht Bach, Meer sollte er heißen“ zum Ausdruck kommt.

In Koroliov's interpretation, Beethoven's C-minor Sonata, Op. 111, is a stirring soul journey through rocky mountains and dark paths, navigating tumultuous rebellion in the first of the two movements, "Maestoso – Allegro con brio ed appassionato," all the way to a serene letting go in an otherworldly luminous certainty. However, Koroliov's playing doesn't stylize Beethoven into a titan; instead, it accompanies a torn individual through life conflicts, empathetically listening to the unsaid, until, at the end of the Arietta, finding peace in the expression of the ineffable.

Hans-Juergen Fink

Image Hifi –

(...) With Koroliov, the combination of the poetic with the objective is repeatedly fascinating – as it is here. He chooses similarly swift tempos, clearly aligned with the movement titles, as Michael Korstick in his still recommendable complete recording (...), but where Korstick seems to prepare the music with a scalpel for clarity, Koroliov may play even more delicately: he listens extraordinarily finely to the Adagio ma non troppo section from Op. 110, and shapes the ensuing fugue with immense nobility, just to give one example. (...)

Heinz Gelking, Image Hifi

Piano News –

It is already the second CD of Beethoven sonatas presented by the magnificent Evgeni Koroliov. After initially recording Opp. 101 and 106, he now concludes the late sonatas with the triad of the last sonatas. As in the previous production, it is striking how closely Koroliov adheres to the musical score, paying careful attention to the voice leading, phrasing, and dynamic markings. It is a true delight to listen to.

Already in Op. 109, he can bring out every nuance, utilizing not only his unrestricted technique but also his calm and experienced gaze beyond the notes. The final movement of Op. 109 alone is an almost unbeatable confession to Beethoven's intellect, as Koroliov manages to play the 13 minutes of this movement so coherently that the listener is led to understand the encapsulated structure as convincingly and transparently as rarely before. The good thing: Koroliov wants to prove nothing but to act in the service of the music.

And he succeeds in Op. 110 so fascinatingly that one can almost experience how the themes unfold. Once again, the long third movement is the most impressive here, as you can hear, with what a happy instinct the pianist balances the piano sound to lead the chiseled chords on the keys to an even more voluminous sound, rather than a harsh ecstasy. With Opus 111, Koroliov ultimately shows his greatness because in this ostensibly reduced sonata with the Arietta, you can recognize the lyrical balance that the pianist is capable of playing against all the outbursts.

Carsten Dürer, Piano News

KulturSPIEGEL 2/2015 –

(...) Often surprisingly gentle, he savors the poetic nuances (...)

(...) Richness of forms and colors unfolds so naturally that the musical language transcends all mechanics. (...)

Johannes Saltzwedel, KulturSPIEGEL

klassik.com –

--> original review

Here, a free and refined spirit is making music...

Dr. Daniel Krause

Stereoplay –

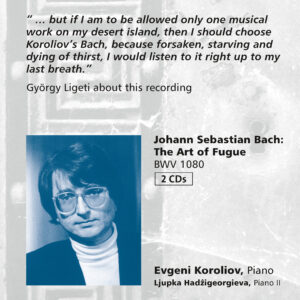

Evgeni Koroliovs Einspielung von Bachs „Die Kunst der Fuge“ faszinierte den Komponisten György Ligeti dermaßen, dass er erklärte, er würde sie mit auf die einsame Insel nehmen, um sie bis zum letzten Atemzug zu hören.

After recording Ludwig van Beethoven's piano sonatas op. 101 and 106 in his series for the label TACET, Koroliov now dedicates Volume XV to the composer's last three sonatas. Applying the formal structuring of a Bach interpreter, Koroliov approaches the music, infusing it with precise voice leading and an unerring sense of formal connections, creating a dramatic tension that entirely eschews extravagance.

Anschließend an das durch Klarheit und Spannung bestechende „Prestissimo“ aus Sonate op. 109 entfaltet er den Schlusssatz mit vollkommener Hingabe an den romantischen Charakter der Musik. Den Kopfsatz der Sonate op. 110 taucht er in delikat schillernde Lichtwerte und versenkt sich im Adagio mit berückender Klangschönheit in die Seelentiefe des Komponisten. Machtvolle Größe, düstere Abgründe und subtile Sinnlichkeit verbindet er im ersten Satz der Sonate op. 111 miteinander.

He transforms the Arietta with technical finesse and interpretative intelligence into a moment of breathtaking concentration and tension. That is musical magic.

Miguel Cabruja, Stereoplay

Pizzicato –

--> original review

Wie Seifenblasen…

Every CD by Evgeni Koroliov brings us joy and satisfaction. His touch, however, moves us particularly in these three final Beethoven sonatas that he recorded in his own series for Tacet. The slow and tranquil movements are of unearthly grace. Here, the 65-year-old pianist demonstrates outstanding artistry. Notes ascend heavenward like small, iridescent soap bubbles. This is not sentimentalism; it is pure beauty. The fact that he imparts a certain Bachian rigor to the faster movements and fugue of the 31st Sonata while combining liveliness with restrained emotion demonstrates the pianist's mastery.

Remy Franck