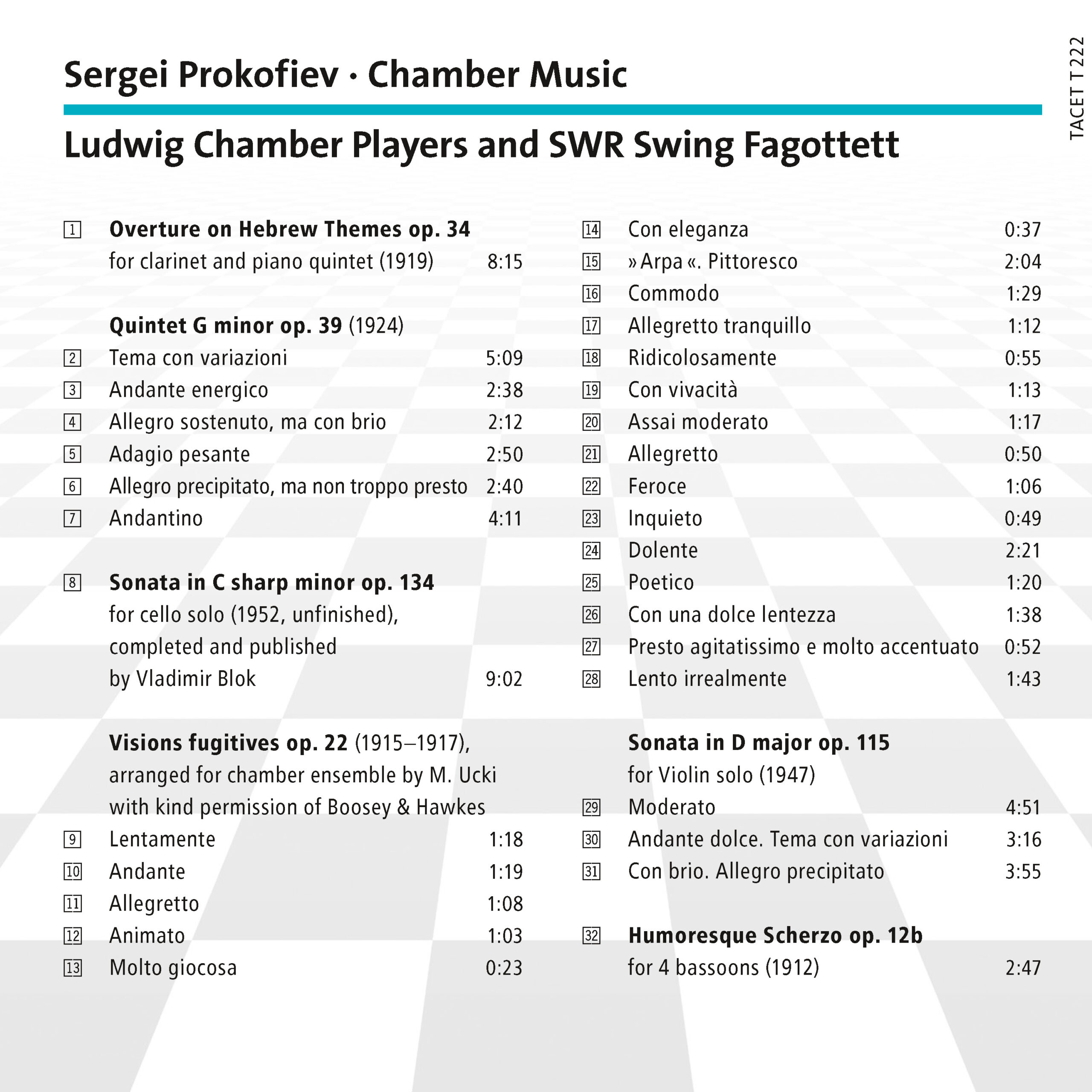

222 CD / Sergei Prokofiev: Overture on Hebrew Themes and other chamber Music

Description

The clarinetist Dirk Altmann came to me and asked if I would like to record Sergei Prokofiev's Quintet. Yes I would, because I know the Ludwig Chamber Players from other recordings, and know how good they are. But what to record with it? The Quintet only lasts a quarter of an hour. What other chamber music is there by Prokofiev? So we went on the search.

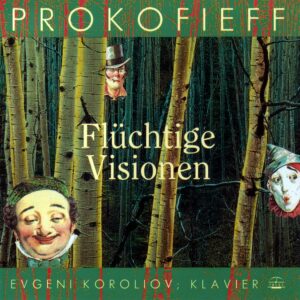

What came out of it is this kaleidoscope of Prokofiev's chamber music output, together with a beautiful new instrumentation of the "Visions Fugitives" for 10 instruments under the pseudonym of M. Ucki. Few composers have been so capricious, stylistically as well as compositionally. Uninhibited boldness, such as the same melody line played simultaneously on different instruments, only with different phrasing, alternating with apparently conventional elements. Places of breathtaking virtuosity and boldness on the one side contrasting with enraptured, tender and melancholic moods on the other from a man who was probably always caught between two stools and wasn't entirely at home anywhere. A cosmopolitan ahead of his time. And always these new, strange harmonies and this typically sarcastic?, resigned?, relentless? Rhythm that fits so well with 20th century Russian history. An adventure. (A. Spreer)

6 reviews for 222 CD / Sergei Prokofiev: Overture on Hebrew Themes and other chamber Music

You must be logged in to post a review.

Fanfare Magazin –

-> Originalrezension auf Englisch

Prokofiev may not have produced many chamber works compared with Shostakovich, but those that feature woodwinds are piquant and delightful. This enjoyable collection from the Ludwig Chamber Players—the name pays homage to Beethoven—begins with the two best-known works, the infectious Overture on Hebrew Themes and the much more modern-sounding Quintet, op. 39. The Overture, dating from 1918, is scored for piano quintet and a Klezmer-ish clarinet; a good deal depends upon how much like an authentic Klezmer player the clarinetist chooses to be. Here the emphasis by Dirk Altmann is more on puckishness, taking a quick pace and not leaning very heavily on the Jewishness of the melodies, by which I mean a combination of nostalgia, shtetl atmosphere, and plaintive wailing.

Shostakovich felt a deep kinship with Russian Jewish culture and ist tragic plight during World War II, but Prokofiev was inspired simply by a commission that came his way while he was living in New York. The clarinetist Simon Bellison from the New York Philharmonic actually provided the tunes, and Prokofiev sketched the whole piece in one day. This new reading is quite captivating.

The same is true for the Ludwigs’ reading of the Quintet, which is in six sharply contrasted movements and dates from 1924 in Paris. Making much of ist “radical” style, the program notes point out that the Quintet, originally commissioned as a possible ballet score, directly preceded the fierce Second Symphony. I find that the piece’s shocking Modernism has settled down considerably. The most marked quality of the score besides ist often dark mood is the unusual scoring for oboe, clarinet, violin, viola, and double bass. The real surprise on the program are ingenious orchestrations of Prokofiev’s Visions fugitives, the French title for 20 piano miniatures he composed between 1915 and 1917; they were premiered by the composer in 1918 a month before he decamped for New York. Since many Russian pianists feel an affinity for these pieces, which the program notes call distinctive and highly individual, capturing the full range of Prokofiev’s keyboard style, it’s my fault that I’ve never much responded to them. But the surprisingly colorful arrangements for 10 instruments (strings, woodwinds, horn, and harp) by M. Ucki, a pseudonym, fascinated me. Each miniature is given ist own instrumental color, varying from tuttis for the whole ensemble to a solo oboe or flute with harp and everything in between. Ucki is adept at matching the instrumentation to the mood Prokofiev wants to establish, and the result is quite winning.

Since the Visions fugitives originated in Russia, we come full circle with Prokofiev’s eventual return home as a permanent resident in 1936, having suffered a frustrating mixture of success and indifference in Paris and America. To represent his last phase, we get three agreeable, fairly negligible works. The Sonata in D from 1947 was originally written for solo violin but got accepted by an approving Soviet music establishment as a student work to be performed by groups of violins in unison. An ill and depleted Prokofiev gained new inspiration in his final phase from Mstislav Rostropovich, 36 years his junior. A planned sonata for solo cello begun in 1952 was never completed, leaving behind only the first movement, which leaves off during the development section. Using the surviving sketches, the movement, marked Andante, was completed by Vladimir Blok after Prokofiev’s death in 1953. It’s a drab affair so far as I can hear, but is sensitively performed here by an unnamed soloist; no one is named in the Violin Sonata, either. (Tacet’s web site is also mum, so I suppose there were contractual issues.) We end with the brief, jocular Humoresque Scherzo for bassoon quartet. How could it not be jocular where bassoons are involved and the performers call themselves the Swing Fagottet?

Completing the package with first-rate recorded sound and literate program notes that follow Prokofiev on his migrations, this CD wins on all counts. There’s enough very good music to offset the works that most listeners will probably experience only once.

Huntley Dent

American Record Guide –

Prokofieff wrote chamber music all through his career, though never much of it; and this illuminating album clearly shows his shifting styles. The program opens with Overture on Hebrew Themes, from the composer’s New York period. Filled with melodic invention and gratifying solos, it has always been popular,though Prokofieff thought it too conventional. The jaunty opening sounds a bit like vernacular music from Fiddler on the Roof—I mean that as a complement. The piece also has moments of touching lyricism.

The 1924 Quintet is the avant-garde Prokofieff, less ingratiating but by no means alienating. I recently heard a superb performance with players from the New York Philharmonic and am still reeling from the work’s sheer oddness, especially the gruff bass solo opening in II and the violent slashing in the Allegro precipato. It’s good to hear it again in this jaunty performance, though the piece is hard to sort out.

There are also fascinating tidbits, including an incomplete cello sonata, elegantly played by Gen Yokosaka; a wacky humoresque scherzo for four bassoons with a mournful trio; and a chamber music arrangement of the Visions Fugitives by M. Ucki. The 1947 sonata for solo violin, played with great verve by Kei Shirai, was written under Soviet supervision, so it is properly tuneful and simple: one can’t, the authorities believed, tax the brains of virtuous Soviet workers. And Prokofieff was perfectly capable of writing ingratiating tunes.

All the performances are lively and engaging, enhanced by a warm recording. The Ludwig Chamber Players have only been around since 2013, but they are rapidly establishing themselves as a first-class ensemble. The addition of the exotic ‘Swing Fagotteta’ for the bassoon scherzo completes a delightful picture.

Jack Sullivan, American Record Guide

klassik.com –

–> zum Originalartikel

With a cleverly compiled selection of works, the Ludwig Chamber Players and the SWR Swing Bassoon take you through Prokofiev's different creative phases. The interpretation demonstrates high musical expressiveness and tonal diversity.

My Classical Notes –

--> original review

What emerges on this recording is this amazing grouping of Prokofiev’s chamber music output, together with a beautiful new instrumentation of the “Visions Fugitives” for 10 instruments.

We get to listen to pieces of great virtuosity and boldness on one side, contrasting with tender and melancholic moods on the other from a composer who was probably always caught between two stools and wasn’t entirely at home anywhere.

Hank Zauderer, My Classical Notes

Klassik heute –

–> zur Originalbesprechung

It will come as no surprise that "the Ludwig Chamber Players (LCP) ... have quickly established themselves as one of the leading chamber ensembles on the international concert stages": this biographical commonplace could have been omitted with confidence from the booklet. And all the more willingly, as the predominantly cheerful program presents us with a splendid Prokofiev, making the umpteenth duplication of the cliché truly superfluous.

Whether it's the cheerful "Haidl-Daidl" of the Hebrew Overture or the cheeky rattling scherzo of the four bassoons, whether it's the flawlessly delivered solo sonata for violin from the years of Soviet folkiness or the hissing, whistling, grunting, and crackling quintet from the time of the second and third symphonies – everything is performed with a genuine joy of playing and captured with excellent sound quality. The same applies to the fragment of the cello solo sonata and especially to the "Fleeting Visions," which are heard here for the first time in a chamber music arrangement. I will continue to prefer the original version because, for me, the airy substances can only maintain their aggregate and tension state through the sensitive touch of the keys. However, it cannot be denied that this small, fine box of treats is imaginatively made and excellently realized. – I would like to hear the group play Webern. That would be a sensation...

Rasmus van Rijn

Pizzicato –

--> original review

Grandiose Prokofiev-CD, musikalisch und klanglich

When it comes to recording and mixing a chamber music ensemble of around a dozen musicians in a way that creates a whole, where each instrument is heard clearly and distinctly without any tonal distortion, Andreas Spreer of Tacet is the right person for the job. He turns this attractive kaleidoscope of Prokofiev's chamber music into a real delight, just like the musicians playing it. The high-resolution sound is truly sensational, even in the CD version.

But let's be honest: the 'Ludwig Chamber Players' and their guests are Prokofiev interpreters of the highest caliber.

Their interpretation of the Quintet op. 39 for oboe, clarinet, violin, viola, and double bass, taken from the ballet music 'Trapeze,' is so well executed that even the listener who knows nothing about the origin of the piece inevitably associates it with circus life. Rarely has the quirky and clownish been heard in such an exciting interpretation as here.

Something quite exquisite is also the arrangement of the piano work 'Visions Fugitives' for a ten-member chamber ensemble. Whoever this M. Ucki may be, responsible for it, he shows a great sense of genuine Prokofiev sound and the fleeting nature of the composition. And the Ludwigs execute it wonderfully and with great refinement.

A special treat concludes the CD, the short 'Humoreske Scherzo' for four bassoons, brilliantly performed by the 'SWR Swing Bassoon Quartet.'

Our Supersonic Award is intended to honor the musicians, but certainly also sound engineer Andreas Spreer.

Remy Franck