177 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. XIII: Theodor Leschetizky

Description

„"Exciting Time-Travelling

(…) this recording [is] a highly interesting, fascinating document. And, at the same time, an artistic thorn with which one might occasionally prick certain contemporaries who merely play each note as written." (klassik.com)

8 reviews for 177 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. XIII: Theodor Leschetizky

You must be logged in to post a review.

Pianiste –

THE LESSONS OF THE PAST

The Magic of the Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados... play their works.

Would you like to hear Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, and Reger playing their own works on a modern piano? And how about a "perfect" restoration of the interpretations by the early Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne, and Schnabel? The German label Tacet offers an anthology of rolls recorded by the Welte-Mignon system. The system is simple, but the process of reproduction is particularly complex! In fact, the pieces played by the composers themselves were digitized from the device invented in 1904 by the company Welte & Sons of Freiburg. The perforated rolls of the time captured the touch, pedal play, and the finest nuances. Today, all that is needed is to transfer these recordings onto a concert piano.

It is therefore a real shock to hear, in optimal listening comfort, Debussy’s Children's Corner and some Préludes, as well as Ravel’s Sonatine and Valses nobles et sentimentales, all played by the composers themselves. What lessons can we take away from this? First, the astonishing freedom with which these two geniuses approach their scores! It is also true that Ravel’s playing is not always flawless… But if we look beyond the purely technical aspect, we notice the extreme finesse and personalization of their touches. The dynamics are generally soft, with the fingers seeming to merely caress the keyboard. No brutality whatsoever. The clarity and gentleness are astounding. Other examples are equally striking, such as the two volumes dedicated to Brahms’ works interpreted by Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney, or Chopin’s Etudes played by Pachmann and Paderewski…

The virtuosity of these pianists is staggering, but even more surprising is the passion, the commitment, and sometimes even the coquettishness, the occasional unnecessary ornamentations that some perform almost as if they were tics. From all these master lessons, we learn that the strongest personalities only flourish after a visceral and profound understanding of the works. Schnabel in the waltzes of Josef Strauss and Josef Lanner (who would dare play this today?), Horowitz in 1926 in some Rachmaninoff Preludes, speak to us. Where does the charisma and charm of their interpretations come from? A mystery.

Every year, Tacet releases three or four new CDs from the Welte-Mignon archives. Worth collecting.

S. F.

_________________________________________________

Original Review in French language

LES LEÇONS DU PASSÉ

La magie des Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… jouent leurs œuvres.

Vous aimeriez entendre Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, Reger jouant sur un piano d’aujourd’hui leurs propres Oeuvres? Et que diriez-vous aussi d’une restitution « parfaite » des interprétations des premiers Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne et autres Schnabel? Le label allemand Tacet propose une anthologie des rouleaux gravés par le procédé Welte-Mignon. Le système est simple, mais le procédé de restitution particulièrement complexe! En effet, les pièces jouées par les compositeurs eux-mêmes ont été numérisées à partir de l’appareil inventé en 1904 par la firme Welte & Fils de Fribourg. Les rouleaux perforés de l’époque ont capté le toucher, le jeu des pédales et les nuances les plus fines. Il suffit aujour¬d’hui de transférer ces témoignages sur un piano de concert.

C’est donc un véritable choc que d’entendre dans un confort d’écoute optimal les Children’s Corner et quelques Préludes par Debussy, mais aussi la Sonatine, les Valses nobles et sentimentales de Ravel sous les doigts des compositeurs. Quelles leçons en retirons-nous? D’abord, l’étonnante liberté de ces deux génies vis-à-vis de leurs partitions! Il est vrai aussi que le jeu de Ravel n’est pas d’une justesse infaillible… Mais si l’on dépasse l’aspect purement technique, on s’aperçoit de l’extrême finesse et de la personnalisation des touchers. Les dynamiques sont généralement faibles, les doigts semblent effleurer le clavier. Sans aucune brutalité. La clarté et la douceur sont stupéfiantes. D’autres exemples sont frappants comme ces deux volumes consacrés à des œuvres de Brahms interprétées par Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney ou bien les Études de Chopin par Pachmann et Paderewski…

La virtuosité des pianistes est stupéfiante, mais on est plus surpris encore par la fougue, l’engagement, parfois même les coquetteries, les ornementations intempestives que certains provoquent comme des tics. De toutes ces leçons de maîtres, on retient que les personnalités les plus fortes ne s’épanouissent qu’après une compréhension viscérale et profonde des œuvres. Schnabel dans les Valses de Josef Strauss et de Josef Lanner (qui oserait jouer cela aujourd’hui ?), Horowitz en 1926 dans quelques Préludes de Rachmaninov nous interpellent. D’où proviennent le charisme et le charme insensés de leurs lectures? Mystère.

Chaque année, Tacet publie trois ou quatre nouveaux CD des archives Welte-Mignon. À thésauriser.

S. F.

Pforzheimer Zeitung –

As a teacher, he mentored such prominent pianists as Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Artur Schnabel, and Mieczysław Horszowski. This has secured Theodor Leschetizky’s place in the history of piano playing. A CD released by TACET featuring his piano roll recordings showcases not only his artistry but also Leschetizky’s ability to compose refined and substantial salon music. The Welte-Mignon rolls, beautifully captured on this well-recorded CD, offer an appealing impression of the Polish pianist’s elegant playing style. Fidelity to the score in the modern sense was not his priority, as the dramatically intensified rendition of Mozart’s Fantasy in C minor clearly demonstrates. In the works by Chopin (…) and Stephen Heller, Leschetizky’s refined use of rubato comes to the fore. This meticulous touch is also a defining feature of his own compositions.

tw

Audiophile Audition –

It is as if Theodor Leschetisky - an important pianist and composer at the time - is actually sitting at the Steinway keyboard.

This is another in the fine series of reissues of Welte Mignon piano rolls from Tacet. The German technology of the first three decades of the 20th century (starting in 1904) was by far the most sophisticated, complex and accurate of any of the piano roll systems. (Sort of a Rolf Goldberg technology.) Tacet’s WM-specialist has meticulously adjusted Tacet’s “Vorsetzer,” which is rolled up to the keyboard of a perfectly-tuned Steinway D, and the stereo recording quality is first rate.

The mystery, of course, is that these really can’t be called historical recordings - it is as if Theodor Leschetisky - an important pianist and composer at the time - is actually sitting at the Steinway’s keyboard. Only the Zenph Studios computer-enhanced re-performances from old 78s and mono tapes are in the same ballpark as far as bringing us closer to historical performances. Those may have the advantage of a more accurate timing element, but the mechanical player-piano feeling is often unnoticeable in the best Welte reproductions.

Young Leschetizky was born in 1830 and was taught by Beethoven’s pupil Carl Czerny. He was described as "a volcano of a man," and was known for his charismatic personality. He was also a respected pedagogue. When he recorded these rolls in 1906 his Farewell Concert was already 20 years behind him, but he clearly enjoyed cutting this little collection of pieces. The only sizeable one is the fascinating Mozart Fantasie in C minor. Once Brahms had poked fun at Leschetizky’s "little trifles," and Leschetizky retorted, "they’re ten times more amusing than yours." Could be.

John Sunier

Pizzicato –

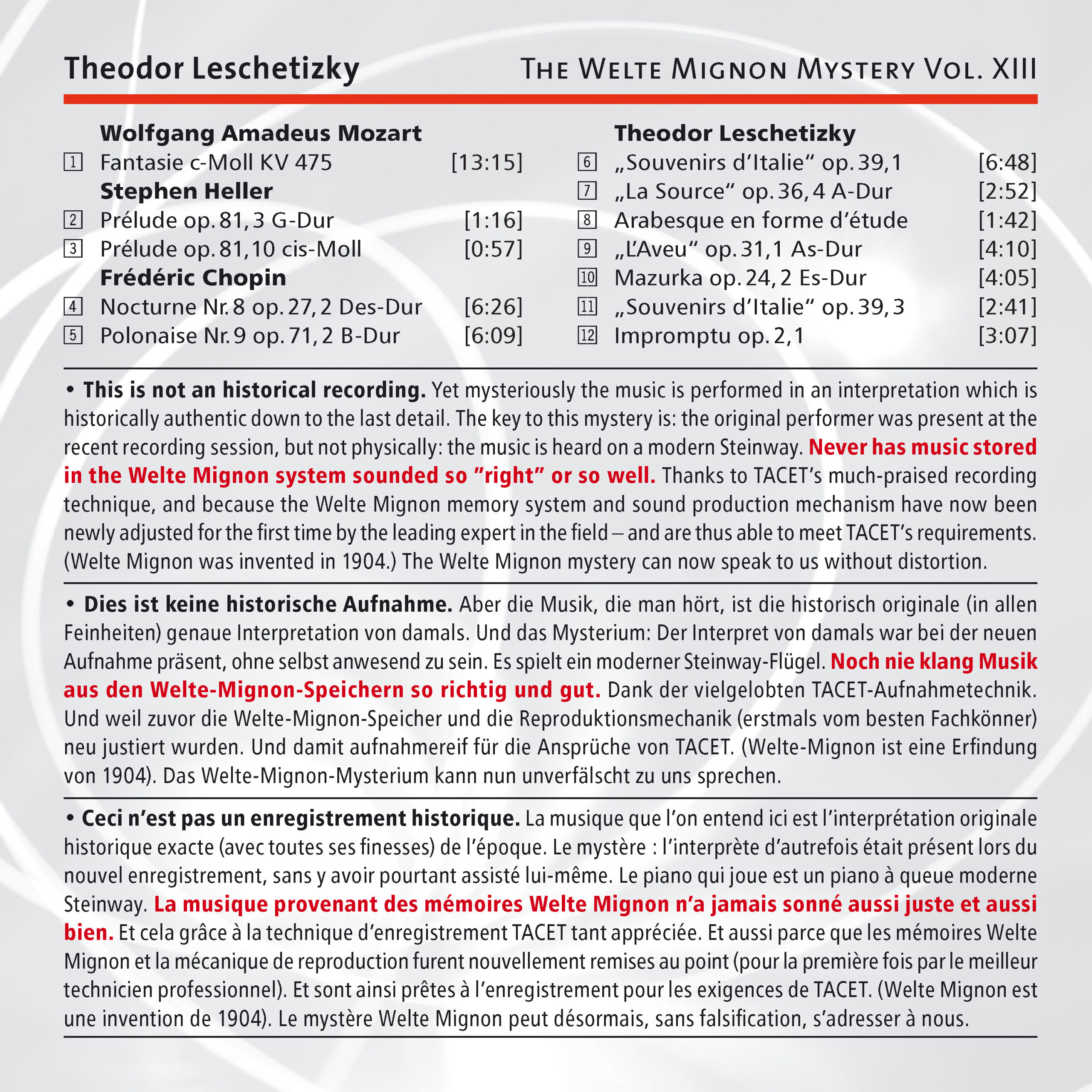

The Polish pianist and composer Theodor Leschetizky (1830–1915) studied in Vienna under Carl Czerny and Simon Sechter. He began teaching at the age of 14 and soon established a name for himself as a concert virtuoso. At 24, he settled in St. Petersburg, where he co-founded the Conservatory in 1862 together with Anton Rubinstein. As such, he is considered one of the founding fathers of the Russian piano school. In 1878, he returned to Vienna. The list of his students reads like a “who’s who”: Ignacy Paderewski, Artur Schnabel, Ossip Gabrilowitsch, Elly Ney, Mieczysław Horszowski, Benno Moiseiwitsch, Paul Wittgenstein, Ignaz Friedman… As a composer, Leschetizky wrote two operas, a piano concerto, songs, and over 70 piano pieces. On January 18, 1906, he recorded seven of these for the Welte-Mignon reproducing piano at the Welte studio in Leipzig, along with five additional compositions. When listening to his highly individual and imaginative interpretations of Mozart’s Fantasy in C minor, KV 475, Chopin’s Nocturne No. 8, and the Polonaise No. 9, one immediately regrets that he did not record more works by well-known composers. However, the exceptional clarity of his playing is just as evident in his own compositions—where clarity should be understood as both transparency and brightness.

RéF

Klassik heute –

There is nothing to object to in the energetic technical efforts to bring old piano roll recordings back to life with today’s sound quality. On the contrary: a reflective listen back to the earliest days of mechanical sound reproduction should become a rewarding obligation for anyone who engages more deeply with music and all its interpretive implications. How much we can learn when, on this occasion, the 76-year-old Theodor Leschetizky once again lays his hands on the keys! Take, for example, the opening Mozart Fantasy in C minor, KV 475: I feel myself (and I deliberately avoid saying “one feels”) transported into a different, unfamiliar, yet utterly fascinating world of expressive subjectivity—far removed from considerations of performance practice, unburdened by fear in handling the printed score, guided solely by personal intuition and feeling. Leschetizky breaks up the opening unison passages—perhaps too unfriendly-sounding for his taste—into a kind of polyphonic layering. Today, any piano teacher would metaphorically rap their student’s fingers with a ruler for such liberties!

On the other hand, in the early 20th century during the Welte Mignon era, there was no established Mozart tradition, no—or hardly any—documented models to follow, and certainly no clear idea of how Mozart himself had performed his works, let alone how they should be played. The true authority was the artist's personality, their aura on stage, and their achievements over a long lifetime of musical activity. And so, today, we are called upon to accept Leschetizky’s idiosyncratic approach to this C minor Fantasy—faithfully, in wonder, at times even in protest—no matter how patchy, unsteady, and yet touching in its details the result may be, as brought into the present by Tacet.

Measured by present-day standards, Leschetizky's rendition of Chopin's D-flat Nocturne is also a testament to the almost uncanny freedom with which he handles the material. In contrast, his interpretation of the posthumously released B-flat Polonaise is not so far removed from current and slightly older interpretations (Magaloff/Philips, Ashkenazy/Decca, Harasiewicz/Philips, Moisiewitsch/Piano Library, Clidat/Forlane, Ugorski/DG, Ferenczy/Hungaroton, for example). Completely in his element—namely, in the realm of elegant, fluid trivialities—Leschetizky revels and whispers his way through the Heller miniatures and his own character pieces. Upon revisiting, much becomes clearer, as several passages of the Mozart Fantasy seem to be played and inspired in the spirit of these "souvenirs," "arabesque," and "impromptu" inventions.

If one wishes to draw a distinction between a major composer and a lesser (though still sympathetic) author, one could compare Leschetizky's lukewarm study of La Source (Op. 36) with Liszt's pre-impressionistic watercolor Au bord d’une source. However, there are merits to be found in the compositional efforts of the minor master: Theodor was well aware of his "crimes of invention in the form of new piano pieces," without any pretense of grandiosity. Christian Schaper adds in his excellent accompanying text: "When Brahms occasionally mocked these 'very small things' during their shared summer holidays, Leschetizky knew how to retort: 'But ten times more amusing than yours.'"

Peter Cossé

klassik.com –

--> original review

(…) this recording [is] a highly interesting, fascinating document. And, at the same time, an artistic thorn with which one might occasionally prick certain contemporaries who merely play each note as written." (klassik.com)

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

Old school

Fewer recordings take us further back into the 19th century than Theodor Leschetizky’s playing on the Welte-Mignon piano – and yet, thanks to modern technology, they sound as if they were made today. At the age of nine, Leschetizky (1830–1915) made music with Mozart's son, Franz Xaver, and at eleven, he became a student of Czerny. He was famous as a pianist and later as a pedagogue. He also composed, writing virtuoso-brilliant salon pieces, some of which are found here. By 1906, his last concert appearance was twenty years behind him. Nevertheless, his playing requires no indulgence. What may confuse us – free rubato, arpeggiated chords, rhythmically slightly delayed entries of the right hand – are not mistakes or personal idiosyncrasies, but rhetoric in the style of the time. In Mozart's C minor Fantasy or in Chopin's D-flat Nocturne, with its beautifully singing touch, we encounter a creative interpreter who fills every note with expression beyond what is written, yet whose performance remains consistently classical in form.

Usc

Journal Frankfurt –

The label Tacet has an interesting series in which the interpretations of Theodor Leschetizky have now been released. How is this possible? After all, he lived from 1830 to 1915. The answer: Welte-Mignon. Those perforated strip machines that recorded piano music in the early 20th century. Tacet has connected the old, preserved roll devices to a modern piano and allows the work to sound as it once did – but with modern recording techniques. A respectable project, which is clearly more than just a technical gimmick, as it conveys the interpretative spirit of the late Romantics.

cru