159 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. IX: Camille Saint-Saëns

Description

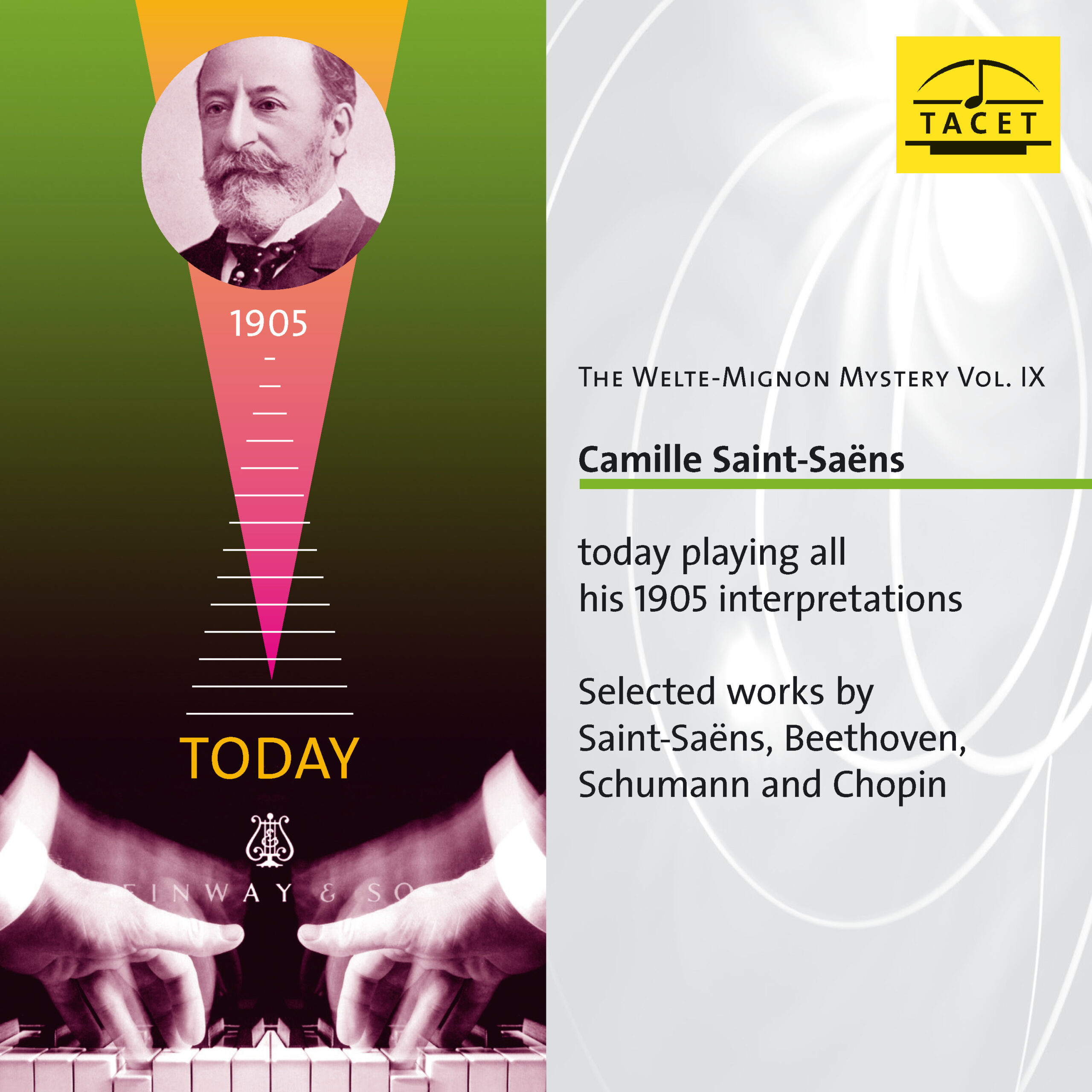

Camille Saint-Saëns was a man of exceptionally wide-ranging talents, a truly universal genius. Yet as a poet, dramatist, philosopher, astronomer, biologist, archaelogist, ethnologist, artist and caricaturist, and even as a pianist, he is completely forgotten; indeed even as a composer he went through a period of neglect. Yet the piano was his constant companion in a matchless career lasting more than three-quarters of a century, from his beginnings as a child prodigy to the last day of his life.

6 reviews for 159 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. IX: Camille Saint-Saëns

You must be logged in to post a review.

Pianiste –

THE LESSONS OF THE PAST

The Magic of the Welte-Mignon

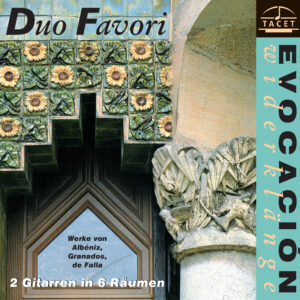

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… spielen ihre Werke.

Would you like to hear Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, and Reger playing their own works on a modern piano? And how about a "perfect" restoration of the interpretations by the early Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne, and Schnabel? The German label Tacet offers an anthology of rolls recorded by the Welte-Mignon system. The system is simple, but the process of reproduction is particularly complex! In fact, the pieces played by the composers themselves were digitized from the device invented in 1904 by the company Welte & Sons of Freiburg. The perforated rolls of the time captured the touch, pedal play, and the finest nuances. Today, all that is needed is to transfer these recordings onto a concert piano.

It is therefore a real shock to hear, in optimal listening comfort, Debussy’s Children's Corner and some Préludes, as well as Ravel’s Sonatine and Valses nobles et sentimentales, all played by the composers themselves. What lessons can we take away from this? First, the astonishing freedom with which these two geniuses approach their scores! It is also true that Ravel’s playing is not always flawless… But if we look beyond the purely technical aspect, we notice the extreme finesse and personalization of their touches. The dynamics are generally soft, with the fingers seeming to merely caress the keyboard. No brutality whatsoever. The clarity and gentleness are astounding. Other examples are equally striking, such as the two volumes dedicated to Brahms’ works interpreted by Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney, or Chopin’s Etudes played by Pachmann and Paderewski…

The virtuosity of these pianists is staggering, but even more surprising is the passion, the commitment, and sometimes even the coquettishness, the occasional unnecessary ornamentations that some perform almost as if they were tics. From all these master lessons, we learn that the strongest personalities only flourish after a visceral and profound understanding of the works. Schnabel in the waltzes of Josef Strauss and Josef Lanner (who would dare play this today?), Horowitz in 1926 in some Rachmaninoff Preludes, speak to us. Where does the charisma and charm of their interpretations come from? A mystery.

Every year, Tacet releases three or four new CDs from the Welte-Mignon archives. Worth collecting.

S. F.

_________________________________________________

Original Review in French language

LES LEÇONS DU PASSÉ

La magie des Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… jouent leurs œuvres.

Vous aimeriez entendre Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, Reger jouant sur un piano d’aujourd’hui leurs propres Oeuvres? Et que diriez-vous aussi d’une restitution « parfaite » des interprétations des premiers Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne et autres Schnabel? Le label allemand Tacet propose une anthologie des rouleaux gravés par le procédé Welte-Mignon. Le système est simple, mais le procédé de restitution particulièrement complexe! En effet, les pièces jouées par les compositeurs eux-mêmes ont été numérisées à partir de l’appareil inventé en 1904 par la firme Welte & Fils de Fribourg. Les rouleaux perforés de l’époque ont capté le toucher, le jeu des pédales et les nuances les plus fines. Il suffit aujour¬d’hui de transférer ces témoignages sur un piano de concert.

C’est donc un véritable choc que d’entendre dans un confort d’écoute optimal les Children’s Corner et quelques Préludes par Debussy, mais aussi la Sonatine, les Valses nobles et sentimentales de Ravel sous les doigts des compositeurs. Quelles leçons en retirons-nous? D’abord, l’étonnante liberté de ces deux génies vis-à-vis de leurs partitions! Il est vrai aussi que le jeu de Ravel n’est pas d’une justesse infaillible… Mais si l’on dépasse l’aspect purement technique, on s’aperçoit de l’extrême finesse et de la personnalisation des touchers. Les dynamiques sont généralement faibles, les doigts semblent effleurer le clavier. Sans aucune brutalité. La clarté et la douceur sont stupéfiantes. D’autres exemples sont frappants comme ces deux volumes consacrés à des œuvres de Brahms interprétées par Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney ou bien les Études de Chopin par Pachmann et Paderewski…

La virtuosité des pianistes est stupéfiante, mais on est plus surpris encore par la fougue, l’engagement, parfois même les coquetteries, les ornementations intempestives que certains provoquent comme des tics. De toutes ces leçons de maîtres, on retient que les personnalités les plus fortes ne s’épanouissent qu’après une compréhension viscérale et profonde des œuvres. Schnabel dans les Valses de Josef Strauss et de Josef Lanner (qui oserait jouer cela aujourd’hui ?), Horowitz en 1926 dans quelques Préludes de Rachmaninov nous interpellent. D’où proviennent le charisme et le charme insensés de leurs lectures? Mystère.

Chaque année, Tacet publie trois ou quatre nouveaux CD des archives Welte-Mignon. À thésauriser.

S. F.

Audiophile Audition –

The redoubtable Saint-Saens performs his own and others’ music with a steadiness of temper and technique.

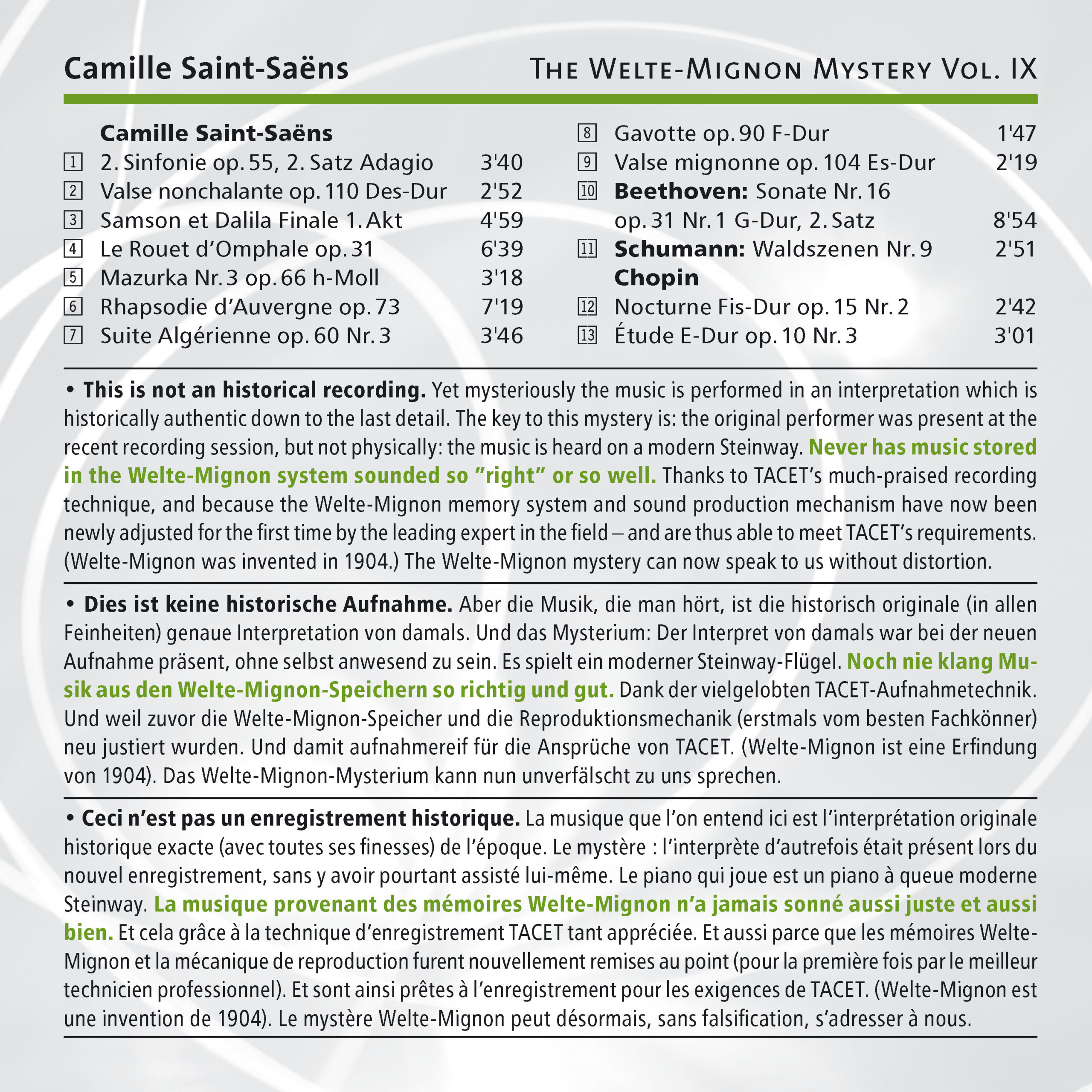

"I produce music the way an apple tree produces apples," quipped Camille Saint-Saens (1835-1921) on his own art. The many-gifted composer and pianist set a number of sophisticated piano roll inscriptions for the Welte studios in 1905, when the composer was seventy years old, now heard on the modern Steinway in stereo. (The Welte system used a "vorsetzer" 88-fingered gadget which rolled up to any piano and "played" it.) Noted for exceptionally quick tempos, Saint-Saens once played his favorite scherzo, Chopin’s C-sharp Minor, for Artur Rubinstein. "It was a picture of note-perfect clarity, but too fast."

The several solo piano pieces are light, salon pieces of rather undistinguished character. In his performance of his own Victor Hugo-based tone-poem, Omphale’s Spinning Wheel, we hear the Bach influence, particularly from the C Major Prelude that sets out WTC I. The Op. 66 Mazurka becomes rhythmically smeared and becomes a toccata, so fast do the arpeggios and runs fly by. The finale from Samson et Dalila - the Dance of the Priestesses of Dagon - enjoys a plastic shape, a daintiness almost rivaling the Beecham performance with orchestra 50 years alter.

A slight ritard between the two hands produces a controlled rubato, and we can hear this in the C Major Rhapsodie d’Auvergne, coloristically adept but rather spare in the use of pedal effects. The light filigree of the middle section - rife with "African", zither, non-legato effects--moves with astonishing facility, the affect close to the Egyptian Concerto. Recall, that for Saint-Saens "Africa" meant Algiers. So the Op. 60 excerpt features swirls of color, internal agogics and dance-rhythms that move in sultry motion. A petite Gavotte in F bristles and chimes along, already indicative of the later composers Ibert and Poulenc. The Valse mignonne in E-flat plays as a stylish bagatelle, another etude brillante with music-box aspirations.

The second movement of the Beethoven G Major Sonata receives a decidedly ‘galant’ treatment and becomes a blend of gavotte and right-hand, ornamental etude. The left hand pulse remains steady, typical of the pedagogy that ruled Hummel and Chopin. The energy seems to evolve from Saint-Saens’ wrists and fingers, the pulse inevitable as Ahab’s pursuit of his destiny. The flurried syncopation at the da capo is quite deft, the top line the soul of etched clarity. The natural affection the French maintain for Schumann comes through in the recording of "Abschied" from the set of Forest-Scenes, its intricate counterpoint and jostling syncopes no obstacles for the redoubtable Saint-Saens. We may well wonder if Saint-Saens’ directness of approach in Chopin carries more truth of that style than any of our modern acolytes’ mannered methods.

The Nocturne is neither prosaic nor self-indulged, but its internal velocity emanates from within. Without pedal, the notes cascade upon each other for a lyrically sober experience. The famed Etude in E moves like clockwork, unsentimentally brisk; the trio, attacca, moves with a blinding rush of notes, the accents sharp until a pregnant ritard and the da capo, almost Spartan in its resistance to change.

Gary Lemco

Klassik heute –

Acoustic glimpses into the past, circa 1905. Camille Saint-Saëns performs his own works, excerpts from his symphonic compositions adapted for piano—and in a completely fearless, that is, by today’s standards stylistically untamed and carefree, manner, also pieces from the classical-romantic repertoire. Those with ears to hear may, for example, take issue with Saint-Saëns’ handling of the slow, whimsically melodic, richly ornamented movement from Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 31, No. 1 (especially if they recall recordings by Kempff, Brendel, or radio broadcasts with Sokolov). Yet how wonderful it is to follow how performers of the time—and in this special case a composer himself—read and interpreted the scores before them. It crackles, wavers, and vibrates; it is an immediate, almost shivering reading, as if the player—without any knowledge of other interpretations—had direct contact with the inherited creations.

Thanks to the Welte-Mignon technology, the sound quality on a modern instrument is excellent. This is therefore only partially a historical recording. Only the interpretive markings provided by Saint-Saëns represent music history from the “Stone Age” of musical recording. One can, in all good conscience, therefore commend the Tacet team: their Welte-Mignon Mystery Vol. IX is part of an initiative that reconciles past and present at the highest technically conceivable level and turns it into an almost touching experience.

Peter Cossé

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

“Tip of the hat, gentlemen, a genius!” With these words, Schumann once greeted Chopin’s debut. Camille Saint-Saëns must also have been a genius at the piano. He was one of the few whom the piano titan Liszt acknowledged as his equal. How much of this fame Saint-Saëns preserved over time can be verified in the Welte-Mignon recordings that the seventy-year-old made in 1905. Alongside sparkling salon pieces and orchestral transcriptions, such as the endlessly whirling Omphale’s Spinning Wheel, there are well-known piano works. He executes the Adagio grazioso from Beethoven’s Sonata in G Major, Op. 31, No. 1 with taut elegance, and Chopin’s F-sharp Major Nocturne Op. 15, No. 2, as well as the famous E Major Etude from Op. 10, with delicacy, grace, and precision. Saint-Saëns’ playing offers us an enlightening glimpse into the classical piano ideal of the 19th century. Brisk tempi, sparkling runs, and a light touch combine with expansive rubato and the frequently employed stylistic device of the hands drifting apart—likely a legacy of Chopin still evident in Alfred Cortot. (…) A genuine revelation, one that can rightly be called sensational!

usc

klassik.com –

--> original review

(…) One can rightly speak of one of the most interesting and significant current projects in the field of piano music when these piano rolls are systematically recorded, thereby making their content accessible to the general public. As part of the The Welte-Mignon Mystery series, the Tacet label is engaged in this commendable task; (…)

NDR Kultur –

Today they are primarily recognized as composers: Bach and Mozart, as well as Richard Strauss, Hindemith, or Shostakovich. Yet the musicians of the past were always also performers. Only through the possibilities of sound recording could it be documented for posterity how composers performed their own works or those of their colleagues. The Welte-Mignon series from the Tacet label has already restored a number of early piano recordings. The most recent CD is dedicated to Camille Saint-Saëns.

When is a prodigy truly a prodigy? When it possesses a photographic memory? When it completes its first piano method in just one month? When, at the age of ten, it can play all 32 Beethoven piano sonatas from memory? If that is the case, then Camille Saint-Saëns was a genuine prodigy.

The final great highlight of Saint-Saëns’ career as a pianist coincided with his 75th stage anniversary. That was in 1921, nine years after the birth of John Cage. His career had begun in 1846, three years before Chopin’s death. In November and December of 1905, the then seventy-year-old Saint-Saëns went to the Welte studio to make recordings on the grand piano there. These recordings are now available on CD in breathtakingly crystal-clear sound quality.

Saint-Saëns’ piano playing is characterized by astonishing lightness. Even the virtuosic passages come off effortlessly and with a certain elegance. The composer plays with airiness and simplicity, sometimes at daringly brisk tempi, as in the following etude by Frédéric Chopin.

His critics occasionally described Saint-Saëns’ piano playing as cool and dry, while his admirers—including the writer Romain Rolland—praised its “perfect clarity.” On this CD, Saint-Saëns also presents arrangements of his own works, including the Rhapsodie d’Auvergne—an unusual blend of local color, salon piece, and concert fantasia.

The significance of this Welte-Mignon series of recordings cannot be overstated. In particular, the recording with Camille Saint-Saëns at the piano provides important insights into the performance practices of the time. The often free shaping of the right hand—against a rigid rhythm in the left—reveals the liberties that musicians allowed themselves at the end of the 19th century. This is all the more remarkable given that Saint-Saëns was especially known as a perfectionist.

Christoph Vratz