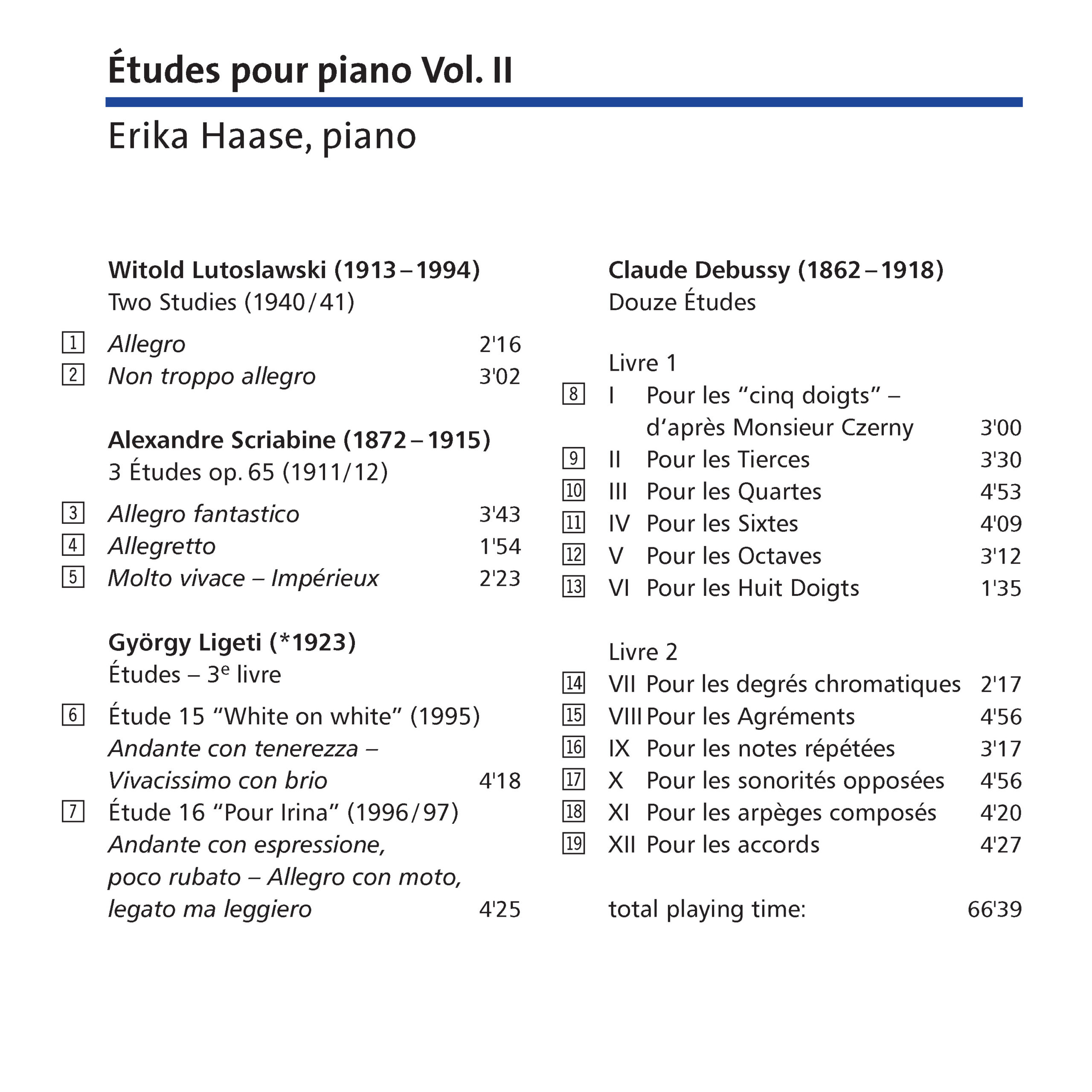

100 CD / Études pour piano Vol. II

Études pour piano Vol. II

Claude Debussy

György Ligeti

Witold Lutoslawski

Alexandre Scriabine

Erika Haase, piano

EAN/barcode: 4009850010005

Recommandé par Répertoire

Description

At the beginning of the 20th century there was not much innovation to be expected from the genre of the piano étude... Apart from Scriabine, Debussy was the first to reach the level of Chopin and Liszt and at the same time enrich the genre. The trailblazing novelty of his "Douze Études" lies in their highly experimental nature; they are études not only for the pianist, but also for the composer... "Erika Haase plays these Études as decisively and confidently as if she had composed them herself." (klassik heute)

9 reviews for 100 CD / Études pour piano Vol. II

You must be logged in to post a review.

ConcertoNet –

This album is the second volume of a series devoted to piano études. A courageous and ambitious undertaking indeed! In an age of the “concept” album, of crossovers and blockbusters, with marketing scientifically calculated, produced in large runs and aimed at a wide audience, this publication may seem rather unappealing: a presentation that is very sober and serious, bordering on icy, with introductory notes that are certainly thorough, yet do not shy away from technical terms (though at least they are translated into French). Moreover, if the producer and pianist Erika Haase (unless others join her later on) are intent on completeness, they will have to traverse not only the well-known pillars of the repertoire, such as the études of Chopin, Liszt, and Rachmaninov, but also rarer, neglected, or reputedly “schoolish” works (for instance, the études of Alkan, Smetana, Hindemith with his Ludus Tonalis, Czerny…). This promises to be both rich and abundant. But what level of sales does Tacet hope for?

Nevertheless, this second volume offers a moment of truly beautiful piano playing that it would be a shame to pass over. In a very skilfully assembled program, Erika Haase, a musician of the highest order, happily combines superb technical mastery with deep sensitivity and an undeniable grasp of the text. Lutosławski’s Deux Études are delivered with the necessary energy, without losing the zest and joy of a piece composed in the difficult circumstances of the Second World War. Shrouded in a dark and unsettling light, the interpretation of Scriabin’s Trois Études can at times appear restless without becoming harsh, vehement, or despairing. Erika Haase is outstanding in Ligeti’s Fifteenth and Sixteenth Études: with great depth, she offers a crystalline sonority that works wonders in these late pages of the Hungarian composer. In Debussy’s Études, the substantial core of the program, Erika Haase demonstrates even more clearly her fabulous ability to characterize each piece and to handle with remarkable assurance the numerous changes of atmosphere in this work. The result is finely crafted études, in which her imaginative playing proves full of humor (Pour les cinq doigts), passion (Pour les tierces), brilliance (Pour les octaves), or a light, springlike touch (Pour les arpèges composés). In the Étude pour les sonorités opposées, Erika Haase wonderfully highlights the originality of this avant-garde page.

Sébastien Foucart

____________________________________

Original Review in French language:

Cet album est le deuxième volume d’une série consacrée aux études pour piano. Entreprise courageuse et ambitieuse que celle-là ! A l’heure du disque « concept », du cross over et du blockbuster, au marketing scientifiquement étudié, à gros tirage et destiné à un large public, cette publication pourra paraître peu séduisante : présentation très sobre et sérieuse, à la limite glaciale, texte de présentation, certes exhaustif, mais n’évitant pas les termes techniques (toutefois, il est traduit en français). De plus, si le producteur et la pianiste Erika Haase (à moins que d’autres la rejoignent ensuite) ont le souci de l’exhaustivité, ils devront non seulement passer par des piliers bien connus du répertoire, comme les études de Chopin, Liszt et Rachmaninov, mais également par des pages plus rares, négligées ou réputées scolaires (par exemple, les études d’Alkan, de Smetana, de Hindemith, avec son Ludus Tonalis, de Czerny…). Cela s’annonce prometteur et copieux. Mais quel niveau de vente Tacet espère-t-il ?

Néanmoins, ce deuxième volume offre un moment de très beau piano qu’il serait dommage de bouder. Dans un programme très adroitement composé, Erika Haase, musicienne de grande classe, conjugue avec bonheur une superbe maîtrise technique, une profonde sensibilité et une indéniable compréhension du texte. Les Deux Etudes de Lutoslawski sont rendues avec l’énergie nécessaire sans que ne soient oubliés l’entrain et la joie de cette page composée dans les circonstances difficiles de la Seconde Guerre Mondiale. Nimbée d’une lumière sombre et inquiétante, l’interprétation des Trois Etudes de Scriabine peut se montrer, par moments, agitée sans être heurtée, véhémente ou angoissante. Erika Haase est remarquable dans les Quinzième et Seizième Etudes de Ligeti : d’une grande profondeur, la pianiste offre une sonorité cristalline qui fait merveille dans ces pages tardives du compositeur hongrois. Dans les Etudes de Debussy, pièce de consistance du programme, Erika Haase démontre davantage encore sa fabuleuse capacité à caractériser chaque pièce et à assurer remarquablement les changements d’atmosphère, nombreux dans cette œuvre. Cela nous donne des Etudes finement travaillées, dans lesquelles son jeu imaginatif s’avère plein d’humour (Pour les cinq doigts), passionné (Pour les tierces), éclatant (Pour les octaves) ou encore léger et printanier (Pour les arpèges composés). Dans l’Etude pour les sonorités opposées, Erika Haase souligne à merveille toute l’originalité de cette page avant-gardiste.“

Sébastien Foucart

Rondo. Das Klassik & Jazz Magazin –

Any pianist who takes on Debussy’s immensely demanding Études—works that are as filigreed as they are obstinate, revealing their charms only with reluctance—and succeeds in convincing with them, is an absolute master of the craft. Conversely, not everyone who is generally regarded as such manages to turn these twelve late masterpieces of Debussy into a personal triumph.

Erika Haase, born in Darmstadt in 1935, can hold her own with the very best. Compared, for instance, with Maurizio Pollini (DG), who offers a forceful, conventionally virtuosic interpretation, she succeeds in unfolding a far more diverse palette of tone colors. Above all, in pieces such as No. 4 (Pour les quartes) and No. 11 (Pour les arpèges composés), she performs true miracles of touch, showing how this music, in its motivic and coloristic multidimensionality, points forward into the future.

At the same time, Erika Haase always remains true to the French ideal of clarity, resisting every urge toward rhapsodizing or thunderous keyboard display—even where this might be tempting, as in the Étude for octaves. Pollini has no hesitation in presenting his powerful paw here, and he does so in an undeniably impressive manner. Ultimately, however, it is Erika Haase’s nuanced and unpretentious playing that probes the hidden depths of Debussy’s seemingly sparse late style with a combination of X-ray vision and refined coloration.

The two Études by Lutosławski are pianistically rewarding yet stylistically still immature youthful works, and the dark ecstasy of Scriabin’s Opus 65 seems less congenial to Erika Haase than Debussy’s crystalline aesthetic. She is, however, fully convincing in two pieces from Ligeti’s still unfinished third book of Études—White on White and Pour Irina. The extra fraction of time she allows herself compared to the equally masterful recordings by Pierre-Laurent Aimard (Sony—see review) and Toros Can (L’empreinte digitale—see review) pays off in added concentration and atmospheric density.

Thomas Schulz

Piano News –

The pianist Erika Haase seems to have a predilection for that musical genre around which others prefer to make a wide detour: the étude, especially those of the 20th century. That she masters this métier brilliantly she had already amply demonstrated a few years ago in a CD of études by Bartók, Stravinsky, Messiaen, and Ligeti. Études pour piano Vol. II continues the earlier étude project, and this production too brings almost nothing but pleasure. Once again, the time frame is stretched as widely as possible: études from the beginning, the middle, and the end of the 20th century, with two freshly composed Ligeti études once more marking the most advanced stage of étude composition in that century.

This time, however, Debussy’s Études take center stage—a cycle long since canonized as a classic. The repertoire value is nevertheless very high, since this obstinate cycle of études is still treated rather stepmotherly by interpreters. Moreover, the performance is consistently on a high level. Erika Haase approaches the Frenchman’s études primarily as poetic miracles that do not exhaust themselves in the exercise-like aspect, but unfold almost unobtrusively, with feline suppleness and refined tonal sensitivity. All the more surprising, then, that the pianist seems to get so little out of Scriabin’s three late Études op. 65. Evidently, the mystical-ecstatic nature of this music is not entirely her element. By contrast, in the two (here recorded for the first time) youthful études by Lutosławski (1940/41), Erika Haase again gives her very best—and Ligeti, of course, she handles as if with ease.

Robert Nemecek

Hannoversche Allgemeine Zeitung –

…Erika Haase strikes a harder note with her second collection of piano études (Tacet 100). Once again, the pianist, who teaches at the Hanover Musikhochschule, proves herself to be as challenging as she is precise, a musician with impeccable instinct for the attacks of Lutosławski’s early studies and the fantastical world of the late-Romantic Scriabin. With flawless meticulousness she plunges into the polyrhythmic subtleties of György Ligeti. Finally, Claude Debussy’s twelve études are launched with a winking nod of respect toward Monsieur Czerny, touch along the way on the accuracy of the baroque master Couperin, and culminate in an exquisitely nuanced panorama of piano timbre sweeping across every register…

Ludolf Baucke

Klassik heute –

After her musically phenomenal and pianistically equally brilliant first CD of piano études (Ligeti, Stravinsky, Bartók, Messiaen; Tacet 53), Erika Haase follows up: just as cogently conceived as it is differentiated in execution, this CD places the two Ligeti Études Nos. 15 and 16 from the Third Book, completed in 1995 and 1996/97, alongside works by Lutosławski and Scriabin, as well as Debussy’s two highly demanding books of Études. Here too her approach convinces once again—an approach worked out perceptibly down to the smallest detail, yet integrating every tiny puzzle piece into a coherent, flowing overall conception. Erika Haase plays these études with a determination and naturalness as if she had conceived them herself. The very notion of the étude recedes into the background: the pianist demonstrates that the label “étude” is far too technically minded. She presents character pieces, each with its own specific level of difficulty (indeed, in Debussy’s case these very technical challenges became the titles of the pieces themselves, yet here they are relegated to a secondary role in terms of musical statement). Slight deductions must be made in matters of sound compared to Études pour piano Vol. II—the first installment was still a shade more open.

Kalle Burmester

Classics Today –

Erika Haase continues her survey of 20th century piano etudes with early Lutoslawski, late Scriabin, late Debussy, and recent Ligeti (no late period for this eternally youthful composer!). The program begins with Lutoslawski′s Two Studies, works that fly across the keyboard in the manner of Bartók′s more unbuttoned virtuosic excursions yet are laced with Lutoslawski′s original brand of harmonic scintillation. Haase is fully up to their finger-twisting demands, although you could imagine greater litheness and energy all around. Similarly, the three Scriabin Op. 65 Etudes seem technically and emotionally reigned in, as if Haase were reluctant to push the third selection′s climactic repeated chords to their requisite fevered pitch. An air of caution permeates the notoriously difficult Etude in Ninths (No. 1), but that′s par for the course in a work for which many pianists systematically ignore the composer′s "Allegro fantastico" indication (not Sviatoslav Richter!). Ligeti′s White on White (Etude No. 15) would benefit from a greater sense of line in the sparse opening and from a brisker, suppler middle section.

Compared to the steely elegance and unruffled poise characterizing Mitsuko Uchida′s reference recording of Debussy′s Etudes, Haase is anything but a sensualist. Her playing abounds in nervous energy, colored by sudden dynamic surges, abrupt accents, and tiny breath marks (not necessarily indicated by the composer, however). Sometimes the results are convincingly subjective (as in the first three etudes, plus the seventh and 10th); other times the musical flow fragments into stiff eccentricity (etudes Nos. 11 and 12, for example). Obviously an intelligent, inquiring musician is at work, and you can′t help but listen to Haase with respect. Then, when no one is looking, pull Florent Boffard′s robust and sexy Debussy Etudes out of your brown paper bag, place the disc in your CD changer, and turn down the lights.

Jed Distler

Répertoire –

The German pianist Erika Haase had already devoted, four years ago, an entire CD to some of the great cycles of 20th-century Études (Ligeti, Bartók, Messiaen, and Stravinsky), a disc at the time awarded a 10(/10) by Répertoire, above all for a truly remarkable overall vision of Ligeti’s Études.

In the meantime, the composer of Le Grand Macabre has embarked on a third book, from which Erika Haase now presents the first two pieces—always interesting, but nevertheless revealing in Ligeti a certain waning of inspiration. Still present are his fine command of form, his acute sense of stagecraft in the organization of sonic events, yet nothing that elevates this beginning of the third book to the same level of fundamental importance as the first two.

Before tackling, at the end of the disc, Debussy’s two books—which remain the cycle princeps, without which this whole 20th-century return to the piano étude as a locus of both demonstrative virtuosity and formal elegance would probably not have happened, or at least not in the same way—Erika Haase allows herself a few less expected excursions: two youthful Études (1940–1941) by Lutosławski, voluble, fluid pieces, still little individualized but certainly agreeable; and above all Scriabin’s late Études, with their elliptical, destabilized, troubling language, which she renders with a variety and delicacy of touch that is simply spellbinding.

With Debussy’s Études, Erika Haase concludes her exploration with a cycle in which digital virtuosity must be complemented by an ever-alert architectural sense. And above all she ventures onto a terrain of particularly fierce discographic competition, where a number of dazzlingly effortless successes (Thiollier, Crosstey) have already been noted, not to mention numerous other interpretations—less sovereign, perhaps, but of constant interest (Pollini, Ciccolini, Béroff, Pludermacher…).

Erika Haase’s Études are those of a true magician of sound: a rounded, supple version, yet without renouncing the exaltation of certain harmonic tensions, rendering these works almost easily accessible. At times, in terms of sheer pianistic potential, this prodigiously comfortable and natural execution shows a few limits (Pour les accords), but one accepts them readily. Let us hope that for some, the release of this brilliant second volume will serve as the decisive stimulus to go in search of the first one (whose presentation has been duly spruced up for the occasion), and thus begin to build their indispensable, reasoned discotheque dedicated to the music of the last century—music destined to settle once and for all into the great repertoire of our own.

Laurent Barthel

_______________________________

Original Review in French language:

La pianiste allemande Erika Haase avait déjà consacré il y a quatre ans un CD complet à certains des grands cycles d′Études du XXe siècle (Ligeti, Bartók, Messiaen et Stravinsky), disque distingué à l′époque par un 10(/10) de Réepertoire, surtout pour une très remarquable vision d′ensemble des Études de Ligeti.

Entre-temps le compositeur du Grand Macabre s′est lancé dans la rédaction d′un 3e Livre, dont Erika Haase peut nous livrer aujourd′hui les deux premières pièces, toujours intéressantes mais qui témoignent quand même chez Ligeti d′un certain affadissement de l′inspiration. Restent présents une très belle maîtrise de la forme, un sens aigu de la mise en scène dans l′organisation des événements sonores, mais pas de quoi hisser ce début de troisième cahier au même niveau d′importance fondamentale que les deux premiers. Avant d′aborder, en fin de disque, les deux Livres de Debussy, qui sont quand même le cycle princeps sans lequel tout ce retour des compositeurs du XXe siècle à l′Étude pianistique en tant que lieu tout à la fois de virtuosité démonstrative et d′élégance formelle, n′aurait sans doute pas eu lieu, ou du moins pas de la même facon, Erika Haase s′accorde quelques excursions moins attendues: deux Études de jeunesse (1940-1941) de Lutoslawski, musiques volubiles, fluides, encore peu caractérisées mais d′un agrément certain, et surtout les Études tardives de Scriabine au langage elliptique, déstabilisé, troublant, qu′elle réussit avec une variété et une délicatesse de toucher ensorcelantes.

Avec les Études de Debussy Erika Haase termine son exploration par un cycle où la virtuosité digitale se doit d′être complétée par un sens architectural perpétuellement en éveil. Et surtout eile s′aventure sur un teirain de concurrence discographique particulièrement âpre, où l′on a déjà pu recenser quelques réussites d′une aisance confondante (Thiollier, Crosstey), sans compter de nombreuses autres visions, moins souveraines mais d′un intérêt constant (Pollini, Ciccolini, Béroff, Pludermacher…).

Les Études d′Erika Haasa sont celles d′une véritable magicienne de la sonorité, version tout en rondeurs, sans pour autant renoncer à l′exaltation de certaines tensions harmoniques, qui rend ces oeuvres d′un accès presque facile. Parfois, en termes de pur potentiel pianistique, cette exécution prodigieuse de confort et de naturel accuse quelques limites (Pour les accords), mais on s′en accommode fort bien. Espérons que pour certains, la parution de ce brillant second volume puisse constituer le stimulus décisif pour les inciter à partir à la recherche du premier (au look dûment amélioré pour l′occasion), et commencer ainsi à édifier leur indispensable discothéque raisonnée consacrée aux musiques du siècle dernier qui vont définitivement s′installer au grand répertoire du nôtre.“

Laurent Barthel

Diapason –

After a first disc (TACET 53) devoted to Stravinsky’s Opus 7, Bartók’s Opus 18, Messiaen’s Quatre Études de rythme, and the first two books of Ligeti (she had already recorded the first, along with the individual pieces and the harpsichord works, for Col legno), Erika Haase continues her exploration of the 20th-century piano étude repertoire. For this second volume in particular, the term étude designates both a specific compositional trait—étude in the sense of compositional study—and at the same time signals the great technical difficulties of execution for the performer—étude in the instrumental sense.

Far removed from the certainties imposed by more homogeneous programs, this trajectory maps out the search for an evolution of the genre, the composers in question all having in common a reference back to Chopin. Explicitly so in Debussy’s case (both books are dedicated to him), more indirectly in the case of Scriabin. In Lutosławski, the lineage runs through Szymanowski; in Ligeti, it is arguably less marked in the third book than in the first two. A single nuance, a single rhythmic value: one hears in White on White and at the beginning of Pour Irina a kind of “integral diatonism,” a musical simplicity that Erika Haase conveys with complete naturalness.

Elsewhere in the program, even if one might at times regret phrasing that is a little too placid or sonorities that are perhaps overly comfortable—and in that sense prefer Pollini’s recording of Debussy’s Études—Erika Haase’s performance is more than honorable.

Karol Beffa

______________________________

Original Review in French language:

Après un premier disque (TACET 53) consacré à l′Opus 7 de Stravinsky, l′Opus 18 de Bartok, aux Quatre Etudes de rythme de Messiaen et deux premiers livres de Ligeti (elle avait déjà enregistré le premier, avec les pièces isolées et l′oeuvre pour clavecin, chez Col legno), Erika Haase poursuit son exploration du répertoire des études pour piano au 20e siecle. Pour ce deuxième volume tout particuliérement, ′l′etude′ désigne une particularité d′écriture – au sens d′étude compositionnelle – en même temps qu′elle signale de très grandes difficultés techniques d′exécution pour l′interprète – au sens d′étude instrumentale. Loin des certitudes qu′imposent des programmes plus homogènes, c′est la quête d′une évolution dans le genre que balise ce parcours, les compositeurs abordés ayant tous en commun de faire référence a Chopin. Explicitement dans le cas de Debussy (les deux cahiers lui sont dédiés), plus indirectement dans le cas de Scriabine . Chez Lutoslawski, la filiation se fait via Szymanowski; chez Ligeti, elle est sans doute moins marquée dans le troisième cahier que dans les deux premiers. Une seule nuance, une seule valeur rythmique: on entend dans White on White et au commencement de Pour Irina une forme de ′diatonisme intégral′, simplicité musicale qu′Erika Haase sait parfaitement rendre. Dans le reste du Programme, même si l′on peut parfois regretter des phrasés un peu trop tranquilles ou des sonorités confortables, et préférer en ce sens, pour les Etudes de Debussy, l′enregistrement de Pollini, la prestation d′Erika Haase est plus qu′honorable.

Karol Beffa

klassik.com –

klassik.com-Empfehlung --> original review

From time to time one has the good fortune to encounter pianists who, after just a few bars—or indeed even a few notes—impress through their enormous strength of musical conviction. It is a kind of “categorical imperative,” an uncompromisingness, with which their own interpretation is asserted consistently and with sovereign authority. To this type of interpreter belongs Erika Haase (…)