183 CD / Frédéric Chopin: Mazurkas

Description

"One has not been able to experience it as beautifully as with the great Russian pianist Evgeni Koroliov for a very long time. (…) Koroliov plays this music with a fascinating feeling for time and rhythm, essentially strict without exaggerated rubati and delays, without anything extrinsic, perfumed or making an effect. This is a pure, pensive, internally directed Chopin that doesn't get lost in Parisian salons but rather in the landscape of Masovia and Kuiavia. This is already now surely one of the most beautiful Chopin CDs of the upcoming anniversary year." (BR, "Leporello")

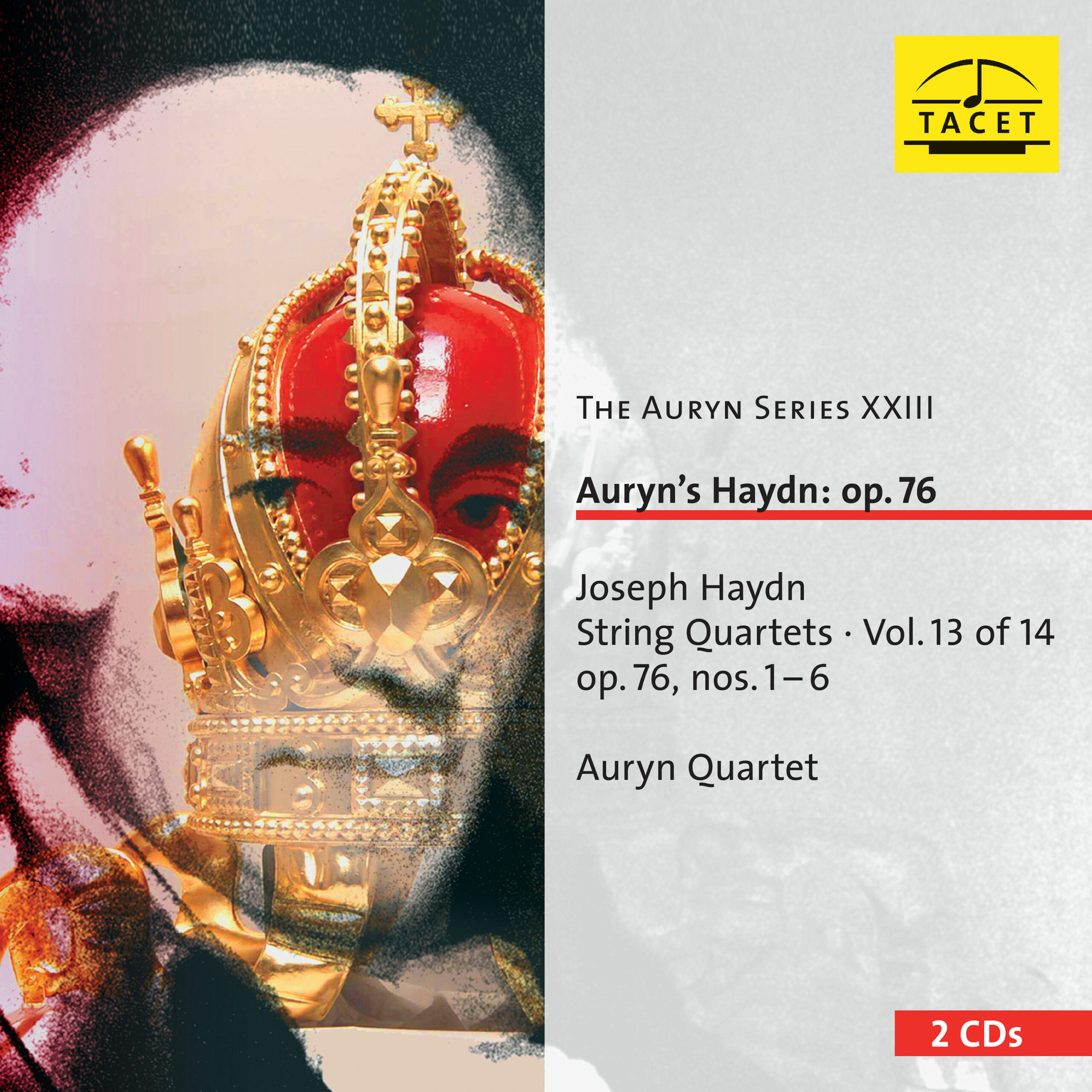

14 reviews for 183 CD / Frédéric Chopin: Mazurkas

You must be logged in to post a review.

NDR-Kultur, Welt der Musik –

Very gently and delicately, Evgeni Koroliov approaches this fragile miniature [the Mazurka in C minor, Op. 30]. He presents it carefully, like a precious glass vessel. With finely nuanced shading of the individual voices, he illuminates the fabric of this small composition. Koroliov traces the magic and melancholy, the shadowed harmonies and the slightly unruly rhythms without any false pathos – a noble interpretation of Chopin.

Elisabeth Richter

Classics Today –

--> original review

A little less than half of Chopin’s complete surviving Mazurkas make up this 2009 release, ordered not according to opus number but for the purpose of an effective program that can sustain one’s interest for 80 minutes. The Mazurkas hold up under many different interpretive game plans, from Ignaz Friedman’s robust, epic statements to the perfumed intimacy of Maryla Jonas and Guiomar Novaes, not to mention Arthur Rubinstein’s three very different complete Mazurka cycles. Koroliov evokes Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli’s lapidarian finger work, wide dynamic range, and subjective poetry. You hear this in Op. 6 No. 1’s fastidious voicing of the central section’s leaps, although Michelangeli’s monumental left-hand droning fifths in Op. 56 No. 2 never lilted like Koroliov’s do here.

The pianist lends interest to the rather uneventful Op. 24 No. 1 by slightly accenting the dissonances, while his gentle way with the implicitly boisterous Op. 7 No. 1 is offset by striking phrase elongations and cross-rhythmic interplay in the deliciously modal Trio. Similarly, Op. 24 No. 2’s pared down outer sections contrast to the surprisingly rolled, loud A-flat major chords announcing its Trio. In fact, Koroliov is not averse to arpeggiating chords at will, or playing the left hand slightly before the right, dead pianist style, yet he employs these devices wisely. Deft polyphonic control justifies Koroliov’s admittedly pulled-about Op. 24 No. 4 and Op. 56 No. 3, while his mesmerizing legato control in the A minor "Émile Gaillard" Mazurka similarly convinces you that his unorthodox slow tempo is a plausible alternative.

Koroliov’s Chopin Mazurkas aren’t so much dances as distinct and diversified dramas, and he brings off his conceptions without a trace of ambiguity, whether or not you agree with the pianist’s every step. Tacet provides superb engineering and fulsome, high-handed annotations.

Jed Distler

© 2014 ClassicsToday.com

Fanfare-Magazin –

(...) I have always revered Rubinstein’s performances and Evgeni Koroliov’s are in the same vein. Koroliov’s mazurkas are above all, songful. He plays with full, rounded tone, relatively leisurely pacing, and is more likely to let things dissolve into reverie than to supply extra nervous energy. He plays with a certain reserve, but with plenty of rhythmic lilt, elegance, and subtle rubato. It was a pleasure to listen to all 25 at one sitting. (...) For warm-hearted performances that are more nostalgic than jaunty and more introspective than aggressive, Evgeni Koroliov is highly recommended. He is helped by a flattering acoustic in Tacet’s recording.

Paul Orgel

klassik.com –

--> original review

(…) In 2010 – the 200th anniversary of the composer’s birth – quite a number of Chopin recordings will be released. That this one will rank among the best can be taken as certain. If the “Chopin Year” were to end now, before it even begins – it would already have yielded richer rewards than expected.

Klassik heute –

Everything I have heard—more precisely, experienced—so far with the now 60-year-old Moscow-born pianist Evgeni Koroliov has pointed to an uncompromisingly serious interpreter, almost fanatically devoted to the works entrusted to him. I am reminded, for example, of his glassy-static, meticulously researched Debussy Préludes (Tacet 131), which gave the impression of being utterly alone at night in an imaginary gallery of images—fascinating and unsettling at once!

It is no different, in my view, when Koroliov embarks on his chronologically erratic journey through the world of Chopin’s mazurkas. Openly joyful expressions, naturalness, or a healthy dance-like vitality—in the sense of a positive embrace of folkloric elements—are pushed into the background in favor of an approach that denies, or at least questions, the legitimacy of these familiar traits so frequently documented in countless recordings. On the other hand, Koroliov succeeds in relentlessly exposing the at times daringly artificial, the cleverly constructed nature of these miniatures. Unlike Rubinstein, who once blissfully lost himself in the stomping, surging, and singing alchemy of dance and sound that defines this small form, Koroliov takes on the role of a kind of pianistic forensic examiner, uncovering the inner workings of musical tissue and skeletal structure. He moves on that much-debated aesthetic plane inhabited by the likes of Benedetti Michelangeli and Valery Afanassiev—pianists who earned both praise and criticism for their provocatively “un-Polish” frost-flower mazurkas. This is thus a sequence of mazurkas that prompts reflection, that acknowledges the discomforts of rural life, and that offers an invitation to rediscover—unprejudiced and anew—a composer who is generally regarded as a well-known acquaintance and marketed as such.

Peter Cossé

Classica –

--> original review in French language

With Koroliov’s “Mazurkas,” one discovers Chopin anew – not the one from concert examination repertoires, but the composer who touches the heart.

This is one of the most demanding piano programs: 25 mazurkas by Chopin strung together. These pieces, which are usually enjoyed in small doses, could, when played for over an hour, provoke uncontrollable fatigue. But nothing of the sort with this magician Koroliov! His approach seems to be the exact opposite of what Ido Bar Shaï offered in a recently released, similar anthology (Mirare). The young, talented pianist let every note reveal his desire to “shape” in a way that had never been done before. Evgeni Koroliov, however, does not “shape” – he is. His subjectivity seems to completely recede behind the work he serves, much like in his famous recording of The Well-Tempered Clavier (Tacet), which György Ligeti referred to as the only recording he would take with him to a deserted island!

We already have at least two sublime complete recordings of the Mazurkas – those by Rubinstein (RCA) and Luisada (DG) – but this wondrous album should certainly be added to them. Everything flows here with grace, lightness, and elegance – without any noticeable effort. All materiality and the worldly are dissolved – only the music remains in its purest form. These diary pages, testimonies of an entire life, sometimes brightened by folk memories, but more often imbued with painful melancholy and consuming nostalgia, strike directly at our hearts – all the way to that last, posthumously published page (Op. 68 No. 4), where desolate chromatics leave the impression of total dissolution into nothingness.

Philippe van den Bosch

_____________________

Original Review in French language

Choc de Classica

–> article original

Avec les „mazurkas“ par Koroliov, on découvre Chopin, non celui des examens de concert, mais le compositeur qui touche au cœur.

Voici l’un des plus redoutables programmes pianistiques : 25 Mazurkas de Chopin enchaînées. Ces pages que l’on goûte volontiers à petites doses, risquent en effet, à être égrenées plus d’une heure durant, de provoquer une incoercible lassitude. Mais rien de tel avec ce sorcier de Koroliov ! Sa démarche ici paraît juste l’inverse de celle de Ido Bar Shaï dans une récente et semblable anthologie (Mirare). Le jeune et talentueux pianiste laissait à chaque instant transparaître sa volonté de „faire“ délicat et raffiné comme jamais personne avant. Evgueni Koroliov, lui, ne „fait“ pas, il „est“. Sa subjectivité semble s’effacer derrière l’œuvre à servir, comme dans sa fameuse gravure du Clavier bien tempéré (Tacet) que György Ligeti déclarait choisir comme unique enregistrement à emporter sur l’île déserte !

Nous bénéficions d’au moins deux sublimes intégrales des Mazurkas signées Rubinstein (RCA) et Luisada (DG), mais il convient de leur adjoindre ce disque miraculeux. Tout passe ici avec grâce, fluidité, élégance, sans aucun effort apparent. Toutes matérialités et contingences abolies, il ne reste plus que la musique, dans sa pureté. Ces journaux intimes, recueils de toute une vie, parfois égayés de quelques souvenirs populaires, le plus souvent imprégnés d’une mélancolie poignante, d’une nostalgie dévorante, nous touchent au cœur, jusqu’à cette ultime page opus posthume (op. 68 n° 4), où les chromatismes désolés donnent une impression de dissolution dans le néant.

Philippe van den Bosch

Piano News –

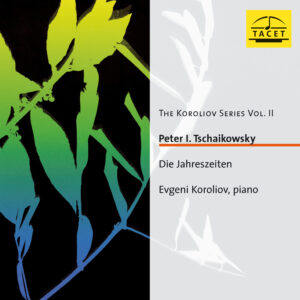

It is a fascinating compositional principle that Chopin has applied to his mazurkas: Unlike his other miniature forms such as the Nocturnes, Waltzes, or Études, these pieces retreat entirely into the shell of their inner world. They know neither explosive moments nor the grotesque thematic distortions that undermine the subject with so much dynamite, which, as Schumann famously quipped, are really "cannons buried under flowers." Here, on the other hand, everything is overshadowed by a clownish sorrow, and the music flows in perfect melancholy. Evgeni Koroliov captures the interpretive subtleties associated with this sound language beautifully in Volume XI of the "Koroliov Series." Thanks to his sensitivity to structural clarity and his unruffled, melody-focused playing, he creates (as in the unspeakably sad A minor Mazurka Op. 17) luminous gems that once again showcase the great craftsmanship of the Moscow-born pianist. In the mazurkas, Bach’s influence is also repeatedly audible, as Koroliov has been deeply connected to Bach since his earliest youth. The fact that Bach and Chopin are much more closely linked through the thread of polyphony than is commonly assumed is also beautifully evident in this recording.

Rafael Sala

Pizzicato –

The Beauty of the Mazurka

The mazurka, throughout Chopin's life, is a kind of return to Poland, often melancholic, sometimes dramatic, and occasionally sunny.

Evgeni Koroliov selected 25 of these for this album. He approaches them in a very introverted, delicate way, entirely within the composer’s intimate realm. The pianist conceives the mazurka primarily as lyrical poetry, within which feelings of revolt or joy may sometimes be the most surprising. However, don’t think for a moment that Koroliov emphasizes sentimentality in his Chopin. Quite the opposite, his playing is marked by a restrained style, exploring rhythms and colors with remarkable accuracy. What creates the atmosphere is the beauty of the sound itself. It is this beauty that gives depth to his interpretations, proving that Karajan was right when he said that beauty is the essence of music. In a world that is often far from beautiful, this quest for beauty is an asset. We should be grateful to Koroliov for allowing us to experience these moments of beauty.

RéF

___________________________________

Original Review in French language

La Beauté de la Mazurka

La Mazurka est, tout au long de la vie de Chopin, une sorte de retour en Pologne, souvent mélancolique, parfois avec des accents dramatiques, parfois ensoleillé…

Evgeni Koroliov en a choisi 25 pour ce disque. Il les aborde d’une façon très introvertie, très douce, tout dans l’intimité du compositeur, le pianiste conçoit la Mazurka avant tout comme poésie lyrique dans le cadre de laquelle les sentiments de révolte ou de joie ne sont parfois que des plus étonnants. Mais ne croyez surtout pas que Koroliov accentue les sentiments dans son Chopin. Au contraire, il joue d’une manière très sobre, explorant les rythmes et les couleurs avec une justesse confondante. Ce qui crée l’atmosphère, c’est la beauté du son. C’est elle qui donne la profondeur à ses interprétations, prouvant que Karajan avait bien raison de dire que la beauté est l’essence de la musique. Dans un monde qui souvent est loin d’être beau, cette recherche de la beauté est un atout. Soyons donc reconnaissants à Koroliov de nous avoir permis de vivre ces moments de beauté.

RéF

Stereoplay –

„Audiophile CD“

Chopin’s Torn Soul

The true Chopin interpreter is not recognized by his virtuosity, but by how he masters the unassuming, light, and bare pieces. Until now, Evgeni Koroliov, who has made Hamburg his home, was known as a strict, intelligent interpreter of Bach. However, after this first Chopin album, the musician, born in Moscow in 1949, must also be counted among the great Chopin performers.

The mazurkas, which occupied Chopin throughout his life, are his most intimate genre, the mirror of his desolate, torn, profoundly Polish soul. Therefore, they require the highest empathy and absolute confidence in rubato: the challenge is to find the difficult balance between the earthy triple rhythm and the free vocal gesture in the right hand. Koroliov strikes this personal emotional tone with his characteristic blend of rigor and sensitivity. His sound remains consistently direct, austere, and unadorned—refined, as though through Bach's polyphony. And yet, the 60-year-old succeeds in delving much deeper into the painful soul of Chopin than many of the perfumers and sound aesthetes ever have.

Koroliov immerses himself in Chopin’s musical rhetoric, almost meditating, disappearing entirely behind the music. In doing so, his performance gains an incredible objective power, despite the high level of personality he brings to it.

Because he wants to uncover the "naked truth," the essence of the mazurkas, Evgeni Koroliov does not follow the usual chronological order. Instead, he chooses a personal selection of 25 mazurkas, which he links together through intelligently chosen "transitions," creating his own highly suggestive narrative.

Connection lines emerge between pieces that are far apart: one senses that for Chopin, it was always about existential questions, about the search for truth. It becomes clear that the mazurkas, in their inner emotional richness, reflect the full range of his proud, tragic soul—and ultimately offer solace in the midst of desolation.

This is the most suggestive and interesting Chopin album in a long time. The sound is also of intimate presence, yet completely free of embellishments. If one could only take a few CDs to a deserted island, Evgeni Koroliov's masterfully interpreted 25 Chopin Mazurkas would surely be among them.

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

Three-quarter time, twenty-five times, and not a single second monotonous.

One cannot play Chopin's jewels in a more knowledgeable, poetic, or pure manner than Koroliov.

Frank Armbruster

Concerti –

Chopin's 58 mazurkas are mysterious and difficult to pin down. They are not meant to be analyzed, but to be felt, offering deep insights into the composer's inner life. Inspired by the folk music of his Polish homeland, the mazurkas are, nevertheless, entirely original works, as their melancholy and weariness are more typical of Chopin than derived from the character of the mazurka dance itself. With his recording of 25 mazurkas, Evgeni Koroliov proves to be both a skilled and sensitive interpreter, with a deep sense of the changing nuances within the introverted core of these masterpieces.

ES

hifistatement netmagazine –

Until now, Evgeni Koroliov had made a name for himself primarily with his strict, deeply probing interpretations of Bach. After his first Chopin album, which he has dedicated to a selection of mazurkas, the 60-year-old resident of Hamburg must now also be counted among the great Chopin interpreters.

Koroliov captures this personal tonal essence with his characteristic blend of rigor and sensitivity. His tone remains remarkably straightforward, austere, and unadorned throughout—refined, so to speak, by Bach’s polyphony—yet he manages to delve much deeper into the painful soul of Chopin than, for example, many perfumers and sound aesthetes. Koroliov immerses himself in Chopin's musical rhetoric, almost meditating, disappearing completely behind the music. As a result, his playing, despite its high degree of personality, gains an incredible objective power.

This is the most suggestive Chopin album in a long time. And if I could only take three CDs to a desert island, Koroliov's Chopin Mazurkas would be among them.

Attila Csampai

Audiophile Audition –

Chopin’s mazurkas cover the entire span of his creative life and absorb the Polish national style in audacious musical harmony.

Chopin’s 58 mazurkas, written over the entire span of his life, absorb the Polish national style and allow his impulse for dance and vocal keyboard writing full sway. The essence of the mazurka lies in the national rhythm, 3/8, a subtle alternation of the beat between the first beat of the bar which may linger into the second or third beat. Meyerbeer remained convinced that the beat expressed itself in duple time, while Chopin insisted that three beats underlay each gesture. The melodic kernels divide themselves into ternary forms, harkening to bagpipe music, modal expressions in fifths or augmented fourths, slinky scales in Neapolitan or Lydian harmony, any number of keyboard ornaments, and references to gypsy or klezmer music. The epic C Minor, Op. 56, No. 3 provides an excellent case in point of a harmonic labyrinth that can paint mystery as well as rhythmic life to the national dance. As to the form, the mazurka can absorb its national energies from the Poland or Mazovia: Mazurek, Oberek, Ksebka, Kujuwiak, or Sousedska, much as Dvorak had a full arsenal of national styles for his Slavonic Dances.

Russian virtuoso Evgeni Koroliov (b. 1949) plays the Steinway D-274 with a particularly soft patina, so intimacy is the key. The concentration on dynamics increases our attentiveness to harmonic modulation, as in the rich B-flat Minor, Op. 24, No. 4. Chopin’s capacity to build a knotty harmonic tapestry out of a simple dance comes forth in the F Minor, Op. 63, No. 2. Koroliov’s left hand remains rock-like, fixed in the essential meter, while the right roams freely and indulges in tempo rubato. The agonized A Minor, Op. 17, No. 4, which opens with the soft pedal, extends a melancholy song, bleak and haunted. The mazurkas of the late style, like the C-sharp Minor, Op. 63, No. 3 possess a metric subtlety that defies easy definition, since the pulse slides between beats like refined oil. The early mazurkas, on the other hand, assert themselves with the militant arrogance of self-possessed confidence, as in the two from Op. 7. But then so does the C Minor, Op. 56, No. 2 in C Major, whose stomping dance creates three-hand effects. The posthumous Op. 67, No. 4 in A Minor reveals how much lyric poetry can infiltrate the mazurka form. The B Minor Mazurka, Op. 30, No. 2 exploits incremental repetition in assorted color dynamics, the principle that spare means yield the most startling, varied effects; here, a two-bar falling figure played seven times.

The Op. 41, Op. 50, Op. 56, and Op. 33 mazurkas represent Chopin’s time with Georges Sand in Nohant, so the erotic content may be more palpable. This sultry quality becomes evident in the wonderfully inventive C-sharp Minor, Op. 50, No. 3, which spins out a series of balanced measures that caress and vary the same phrase groups. Koroliov follows the C-sharp Minor with the concerto-like B Major Mazurka, Op. 63, No. 1, whose passing turns bespeak a world of ad libitum ornamentation within a fixed rhythm. The E Minor, Op. 41, No. 2 places us in the same thoughtful world as the “Funeral March” Sonata, exquisitely controlled. The earliest mazurka, Op. 68, No. 2 in A Minor proceeds as cautious but noble dance in Lydian mode whose graceful turns, sotto voce, would be veronicas in an elegant bullfight. Both the G-sharp Minor, Op. 33, No. 1 and the A Minor (“a Emile Gaillard”) are further products of the Georges Sand liaison, subtle and arched tunes, whose piquant effects come as much from ritards and silences as from the modally harmonized chords. Finally, the melancholy F Minor Mazurka, Op. 68, No. 4, published posthumously. Dreamy and painfully nostalgic at once, Koroliov gives it a valedictory affect, the sweet sorrow of a parting that looks forward to future trysts.

Gary Lemco

Bayerischer Rundfunk, Leporello –

Frédéric Chopin was 16 years old when he composed his first two Mazurkas. And even his last composition, a Mazurka in F minor, was worked on in October 1849 while he was on his deathbed. It was not easy for Chopin scholars to decipher and complete the sketches of this mysterious work, which is overshadowed by dark shadows and deep resignation.

No, the Mazurkas were far from being trivial occasional works or harmless, friendly salon pieces for Chopin, as they have sometimes been wrongly attributed. There are only a few years in which he did not engage with this form. After he left for the West at the age of 20—first to Vienna, then Stuttgart, and finally Paris—it was in the Mazurkas, above all, that the young Pole kept the often melancholic memory of his homeland, his childhood, and his youth alive.

In the years 1824 and 1825, the young Chopin spends his summer holidays at the estate of a school friend in Szafarnia, located near the provinces of Masovia and Kuyavia. Even as a child, he was fascinated by the songs and dances of the region, and it is here that the roots of the Mazurka lie—the very dance that would accompany Chopin throughout his short life in countless variations, often taking the form of profound narratives of hopelessness and sorrow.

As beautifully as now with the great Russian pianist Evgeni Koroliov, this hasn’t been experienced in a long time. Koroliov has released fantastic recordings of Bach, Prokofiev, Debussy, Schubert, and Schumann in magnificent, profound performances. His interpretation of the Chopin Mazurkas seamlessly joins this list. Koroliov plays this music with a fascinating sense of time and rhythm, essentially strict, without exaggerated rubato or delays, without anything artificial, perfumed, or showy. A lean, thoughtful, inwardly directed, deeply felt Chopin, one who loses himself not in the Parisian salons but rather in the landscapes of Masovia and Kuyavia. Already surely one of the most beautiful Chopin CDs of the upcoming anniversary year.

Oswald Beaujean