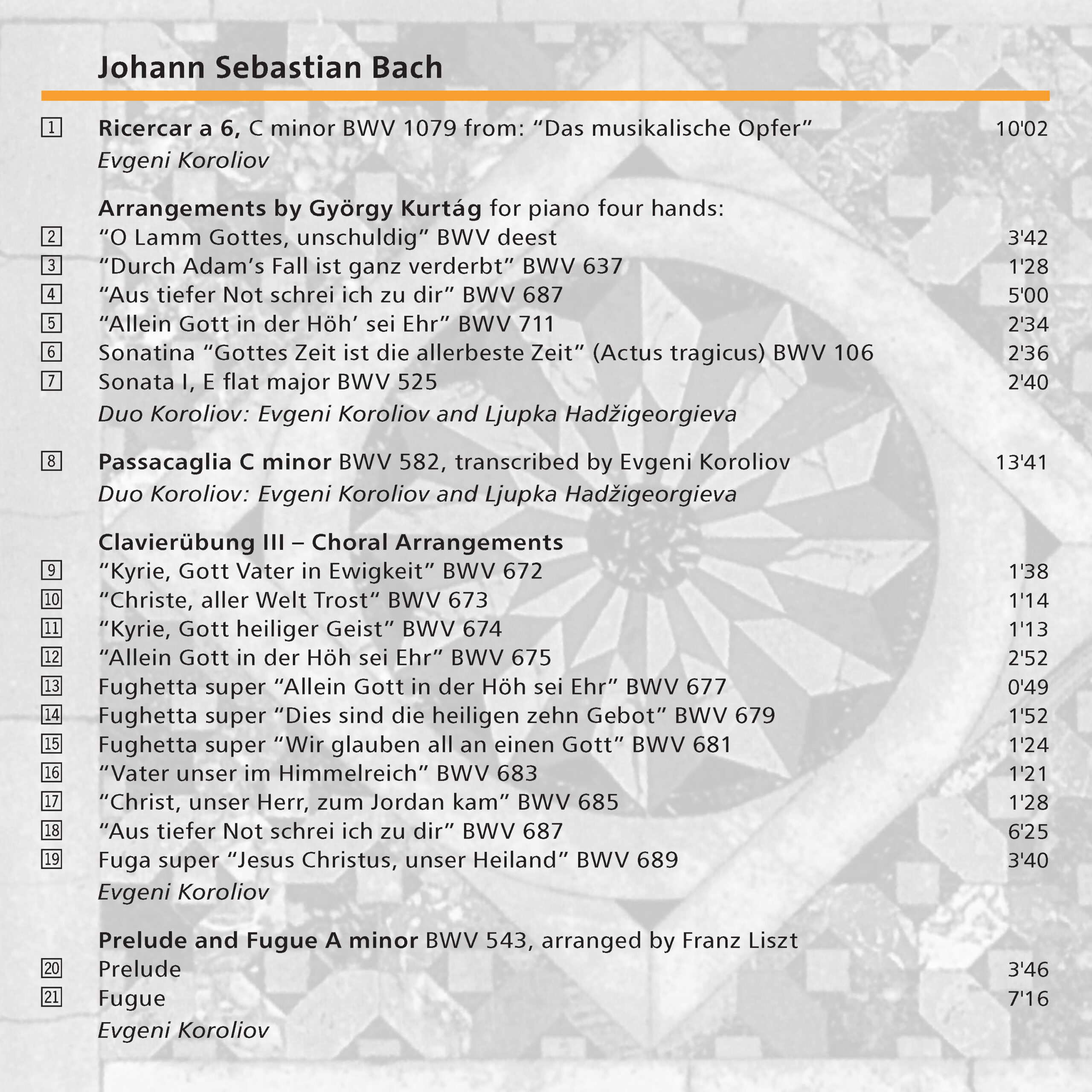

192 CD / Johann Sebastian Bach: Original works and transcriptions for piano

Description

"A merging with the music while forgetting one's self succeeds here, a total concentration in which discipline and zest, regularity and spontaneity are united: a free burning without flickering." (BR klassik)

7 reviews for 192 CD / Johann Sebastian Bach: Original works and transcriptions for piano

You must be logged in to post a review.

Concerti –

--> original review

Bach's Passacaglia in C minor, BWV 582, can only be described as monumental—a fantasia with an orchestral quality. The original is written for organ. Evgeni Koroliov has transcribed it (one could also say: registered it for piano) and arranged it for four hands. A bold undertaking, but a highly successful one. The full grandeur and complexity of the work become evident, especially in the way Koroliov and Ljupka Hadzigeorgieva interpret it: inspired by the spirit of polyphony. This high art is also evident in the other pieces on this recording, whether they are originals or arrangements by György Kurtág and Franz Liszt, for two or four hands. A delight.

Jürgen Otten

Ionarts – Something other than politics in Washington, D.C. –

--> original review

Transcriptions in general—and of Bach’s works or by Bach in particular—are a favorite topic of mine, and I collect recordings that suit that topic in a special box. The pile is ever growing; Marimba versions of the Cello Suites and Goldberg variations variously for harp, accordion, or various saxophone conglomerations abound. My favorite release of 2009—the Goldberg Variations in the Rheinberger-Reger arrangement—belonged to the category as well and this year’s Bach-transcription choice with Evgeni Koroliov and his wife continues very neatly in that line: Adaptations and arrangements for piano duo (and solo piano) by romantic composers (Liszt, Prelude & Fugue in A minor BWV 543), by Bach via-performer (the “Organ Mass” a.k.a. Clavierübung III, which are arrangements of chorales for organ performed on the piano), by the performer (Passacaglia for two pianos), and most delightfully of them all: various organ pieces by György Kurtág for two pianos on the audiophile Tacet label. Taking Bach’s work from the organ to the modern grand piano is perhaps the most ‘natural’ among all the transcriptive steps, despite the fact that they’re based on two as-different-as-can-be ways of producing sound. With all the differences from one organ to another, and considering the piano’s ability to create a great variety of tonal colors (further increased when two pianos are aat work), the piano is really an organ by other means. If the organ is the king of instruments (although I’ve always thought of it, for all its pipes, as more or a resplendent queen or something gender-unspecific), the grand piano is the prince (and workhorse). Leaving the ‘what’, ‘why’, and ‘how’ of transcribing and transcriptions aside for the time being, this disc is an absolute marvel. The work of the creative agents isn’t in this case the equal of their lowest common denominator (which would still be lofty, given the musicians involved), but achieves something as wonderful as—and just-slightly, wonderfully different than—the Bach original. The Passacaglia, so dear to my heart, is oft transcribed and very happily so for two pianos, a version where I feel it can achieve its greatness almost more easily than in an average organ performance. Instigated by Busoni (who never made his own transcription of it), Bösendorfer even designed its Imperial Grand Piano to accommodate Bach’s writing for the grand organ sound of the Passacaglia. Koroliov’s idiomatic transcription is one of several two-piano arrangements (most famous of them probably Max Reger’s). Whether it is Koroliov and Ljupka Hadžigeorgieva’s playing or the transcription (or both) that makes the textures sound occasionally leaner than I am used to from the Reger versions is hard to tell; easy to tell is the propulsive-compelling excellence of the performance, though. Ditto the Liszt and Clavierübung III. Koroliov’s Ricercar a 6 from “The Musical Offering” (a transcription-favorite of mine in Webern’s brilliant orchestrated version) is a superb lead-in for the six Kurtág transcriptions that are such things of beauty that they bring metaphorical, sometimes literal, tears to my eyes. The two and a half minutes of the Sonatina from the Actus Tragicus alone are invaluable, just for the beauty of the piece itself. But if you listen closer, also for how Kurtág teases out the interplay of the voices that, in the original, are made up of two recorders, violas, and da gambas. Elsewhere he emulates overtones by doubling the melody a twelfth above in pppp. Everywhere he exudes musical intelligence and humble passion for the great master’s music.

Taking Bach’s work from the organ to the modern grand piano is perhaps the most ‘natural’ among all the transcriptive steps, despite the fact that they’re based on two as-different-as-can-be ways of producing sound. With all the differences from one organ to another, and considering the piano’s ability to create a great variety of tonal colors (further increased when two pianos are aat work), the piano is really an organ by other means. If the organ is the king of instruments (although I’ve always thought of it, for all its pipes, as more or a resplendent queen or something gender-unspecific), the grand piano is the prince (and workhorse).

Leaving the ‘what’, ‘why’, and ‘how’ of transcribing and transcriptions aside for the time being, this disc is an absolute marvel. The work of the creative agents isn’t in this case the equal of their lowest common denominator (which would still be lofty, given the musicians involved), but achieves something as wonderful as—and just-slightly, wonderfully different than—the Bach original.

The Passacaglia, so dear to my heart, is oft transcribed and very happily so for two pianos, a version where I feel it can achieve its greatness almost more easily than in an average organ performance. Instigated by Busoni (who never made his own transcription of it), Bösendorfer even designed its Imperial Grand Piano to accommodate Bach’s writing for the grand organ sound of the Passacaglia. Koroliov’s idiomatic transcription is one of several two-piano arrangements (most famous of them probably Max Reger’s). Whether it is Koroliov and Ljupka Hadžigeorgieva’s playing or the transcription (or both) that makes the textures sound occasionally leaner than I am used to from the Reger versions is hard to tell; easy to tell is the propulsive-compelling excellence of the performance, though. Ditto the Liszt and Clavierübung III. Koroliov’s Ricercar a 6 from “The Musical Offering” (a transcription-favorite of mine in Webern’s brilliant orchestrated version) is a superb lead-in for the six Kurtág transcriptions that are such things of beauty that they bring metaphorical, sometimes literal, tears to my eyes.

The two and a half minutes of the Sonatina from the Actus Tragicus alone are invaluable, just for the beauty of the piece itself. But if you listen closer, also for how Kurtág teases out the interplay of the voices that, in the original, are made up of two recorders, violas, and da gambas. Elsewhere he emulates overtones by doubling the melody a twelfth above in pppp. Everywhere he exudes musical intelligence and humble passion for the great master’s music.

Jens F. Laurson

Audiophile Audition –

--> original review

Adventurous programming from a pianist who is starting to really make some noise.

This is a very interesting album consisting of arrangements mainly of chorales by Bach. As such it is not the type of page-turner we are normally accustomed to; instead it is meditative and ruminative, an intellectual feast that is not devoid of emotion yet hardly wallows in it.

The Ricercar from A Musical Offering opens the disc as an extended exercise in contrapuntal brilliance, notated on a full six staves. Gyorgy Kurtag contributes some fine transcriptions for piano four hands in six different chorales, expertly done with pointed voice leading and an almost orchestral palate in his sound world. Bach’s Great Organ Mass (Clavierubung III) brought the art of the chorale prelude to unprecedented heights; but many of these pieces are actually only two-manual compositions and make themselves especially suited to the piano.

Rounding out this program are the Prelude and Fugue in A minor as arranged by Liszt (from six pieces of that name) and Koroliov’s own very effective and intelligent realization of the great Passacaglia and Fugue in C minor, done here in one the most effective arrangements I have heard.

Koroliov is one of the great under-the-radar-pianists playing today, though that is slowly changing. This disc won’t be for everyone, but for those with a taste for all things Bach, it will become a staple. Very clear and resonant piano sound.

Steven Ritter

klassik.com –

--> original review

(…) The passion that Evgeni Koroliov puts into his piano playing reaches the listener directly. His interpretations captivate the listener, move them, and touch them. Koroliov's new Bach recording is therefore highly recommended.

Klassik heute –

--> original review

On his journey through Bach's piano cosmos, Evgeni Koroliov repeatedly ventures into the challenging realms of the most erudite counterpoint, even after his famous recording of The Art of Fugue. Works like the six-voice Ricercar from The Musical Offering are so intricately constructed that the experience of fully unfolded harmonic complexity will reveal itself exclusively to the performer, in whose hands all the threads come together. However, for the listener following along with the score, the piece becomes a wonderful musical-intellectual endeavor, provided they have enough time and a solid understanding of Baroque counterpoint. On the other hand, the Ricercar can also captivate the casual listener—as long as they are open to music that forgoes any worldly gestures for ten minutes, that doesn't need to impress anyone, and that appears so unspectacular in its consummate mastery.

This Zen-like calm, which Bach's art exudes in such moments, is the defining characteristic of the CD. The two main works, the Ricercar and the C minor Organ Passacaglia in Koroliov's four-hand arrangement, stand out due to their length, musical density, and enormous difficulty, demanding the full skill of Evgeni Koroliov and his partner Ljupka Hadzigeorgieva. In contrast, the shorter chorale preludes from the third part of the Clavierübung form a kaleidoscope of Baroque miniatures, sometimes soothing, sometimes meditative, sometimes deliberately austere, and always set very simply by Bach. Similarly economical is György Kurtág's arrangement of a selection of other chorale preludes for piano four hands, demonstrating once again his great art of opening vast soundscapes with just a few notes. The only piece that deliberately showcases many notes and technical challenges is Liszt's transcription of the Organ Prelude and Fugue in A minor at the end of the CD. Yet even here, Koroliov focuses on the inner rigor of a structured composition and avoids the virtuosic showmanship of the late Romantic style with which Franz Liszt knew how to present this piece effectively to an audience.

Much could be written about the details of the interpretation—but given the high quality and lifelong engagement with Bach that characterizes the playing of Evgeni Koroliov and Ljupka Hadzigeorgieva, even this would be more of an intellectual exercise than truly necessary. It seems more significant to point out the meditative magic of the works gathered here and to pay respect to the two pianists for the tremendous effort behind this recording. This has resulted in an album that can offer us something rare: the ability to hear the unconscious, private part of ourselves resonate in Bach's music, something we only become aware of when everything within us comes to rest.

Henri Ducard

NDR Kultur –

(…) When Koroliov plays Bach, one is truly "moved" in the truest sense of the word.

There are few pianists who engage with Bach's musical cosmos with such humility, yet with such seriousness and depth. A sense of calm and clarity is conveyed, along with precision in detail and a refined sense of sound.

There is nothing superfluous or unnecessary in Koroliov's Bach playing (…)

Elisabeth Richter

Bayern 4 Klassik Radio –

(…) Koroliov is passionate about chess, interested in medieval art and philosophy—and completely at odds with the typical marketing mechanisms of major labels. He wouldn't even pass as an eccentric genius. His art is rigorous and uncompromising—but there is nothing demonstrative, nothing polemical, no mannerisms, no staging. He has nothing to prove; he has only the musical score and his spiritually clear, highly concentrated piano playing.

(…) It is fascinating how Koroliov (partly in four-handed collaboration with his wife Ljupka Hadžigeorgieva) repeatedly brings out the characteristic timbres and registers of the organ. The subtle poetry of his infinitely nuanced touch does not detract from the structural clarity of his playing. Intellect and emotion harmoniously unite. The "Clavierübungen" become spiritual exercises in which the concept of "practice" loses all sense of external determination, any hint of asceticism and toil. Here, there is a selfless immersion in the music, a total concentration in which discipline and pleasure, lawfulness and spontaneity unite: a steady flame without flickering.

Bernhard Neuhoff