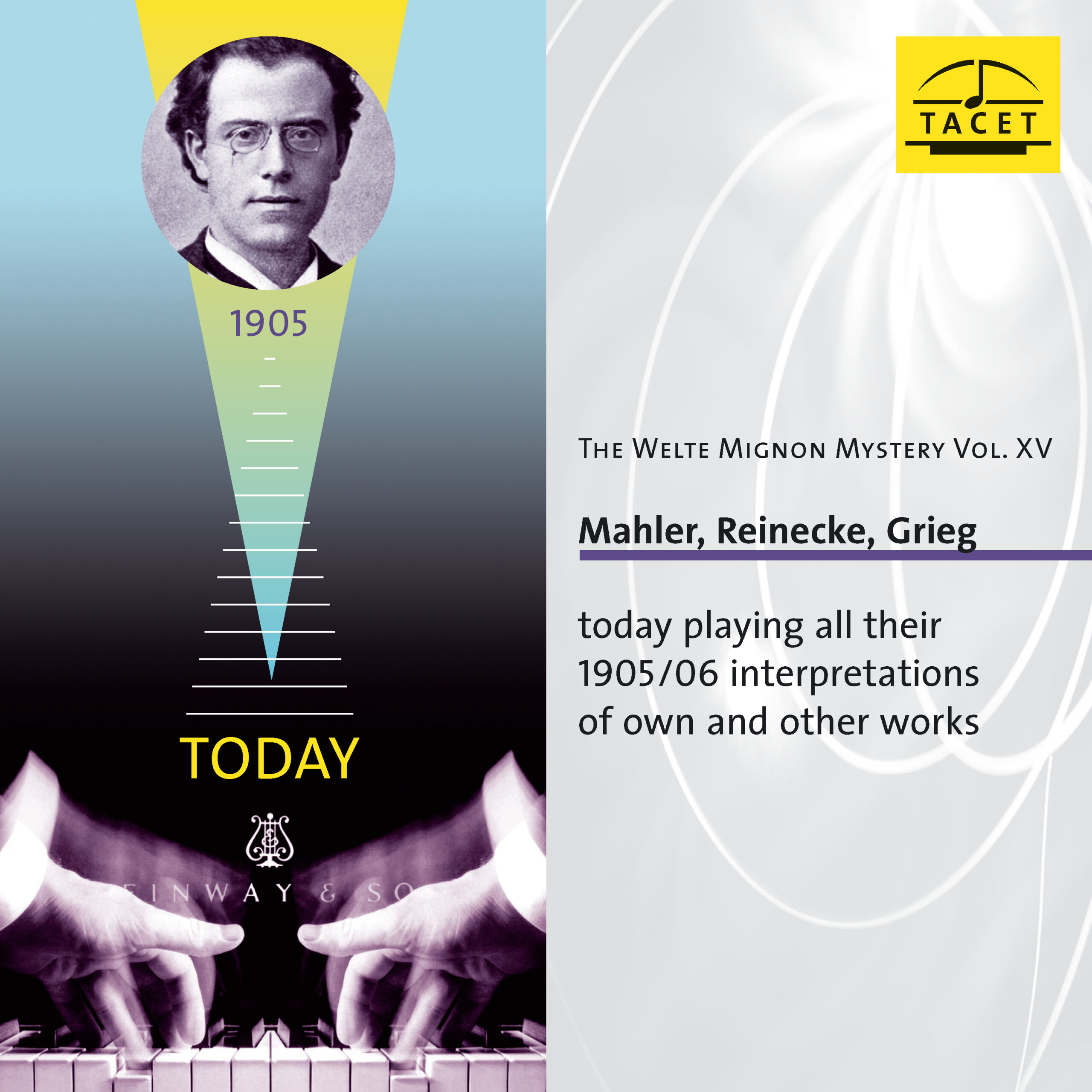

179 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. XV: Mahler, Reinecke, Grieg

Description

"The Steinway used by TACET makes the three composers seem like contemporaries - that's how present and delicate this sound is. It fully meets the highest standards. How wonderful it is the way the grand piabno learns to sing under Mahler's and Reinecke's touch. It is for this reason, above all, that it is worth hearing this recording, even if one already knows the recording of the three composers from other productions: the sound speaks for itself." (klassik.com)

4 reviews for 179 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. XV: Mahler, Reinecke, Grieg

You must be logged in to post a review.

Pianiste –

THE LESSONS OF THE PAST

The Magic of the Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados... play their works.

Would you like to hear Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, and Reger playing their own works on a modern piano? And how about a "perfect" restoration of the interpretations by the early Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne, and Schnabel? The German label Tacet offers an anthology of rolls recorded by the Welte-Mignon system. The system is simple, but the process of reproduction is particularly complex! In fact, the pieces played by the composers themselves were digitized from the device invented in 1904 by the company Welte & Sons of Freiburg. The perforated rolls of the time captured the touch, pedal play, and the finest nuances. Today, all that is needed is to transfer these recordings onto a concert piano.

It is therefore a real shock to hear, in optimal listening comfort, Debussy’s Children's Corner and some Préludes, as well as Ravel’s Sonatine and Valses nobles et sentimentales, all played by the composers themselves. What lessons can we take away from this? First, the astonishing freedom with which these two geniuses approach their scores! It is also true that Ravel’s playing is not always flawless… But if we look beyond the purely technical aspect, we notice the extreme finesse and personalization of their touches. The dynamics are generally soft, with the fingers seeming to merely caress the keyboard. No brutality whatsoever. The clarity and gentleness are astounding. Other examples are equally striking, such as the two volumes dedicated to Brahms’ works interpreted by Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney, or Chopin’s Etudes played by Pachmann and Paderewski…

The virtuosity of these pianists is staggering, but even more surprising is the passion, the commitment, and sometimes even the coquettishness, the occasional unnecessary ornamentations that some perform almost as if they were tics. From all these master lessons, we learn that the strongest personalities only flourish after a visceral and profound understanding of the works. Schnabel in the waltzes of Josef Strauss and Josef Lanner (who would dare play this today?), Horowitz in 1926 in some Rachmaninoff Preludes, speak to us. Where does the charisma and charm of their interpretations come from? A mystery.

Every year, Tacet releases three or four new CDs from the Welte-Mignon archives. Worth collecting.

S. F.

_________________________________________________

Original Review in French language

LES LEÇONS DU PASSÉ

La magie des Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… jouent leurs œuvres.

Vous aimeriez entendre Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, Reger jouant sur un piano d’aujourd’hui leurs propres Oeuvres? Et que diriez-vous aussi d’une restitution « parfaite » des interprétations des premiers Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne et autres Schnabel? Le label allemand Tacet propose une anthologie des rouleaux gravés par le procédé Welte-Mignon. Le système est simple, mais le procédé de restitution particulièrement complexe! En effet, les pièces jouées par les compositeurs eux-mêmes ont été numérisées à partir de l’appareil inventé en 1904 par la firme Welte & Fils de Fribourg. Les rouleaux perforés de l’époque ont capté le toucher, le jeu des pédales et les nuances les plus fines. Il suffit aujour¬d’hui de transférer ces témoignages sur un piano de concert.

C’est donc un véritable choc que d’entendre dans un confort d’écoute optimal les Children’s Corner et quelques Préludes par Debussy, mais aussi la Sonatine, les Valses nobles et sentimentales de Ravel sous les doigts des compositeurs. Quelles leçons en retirons-nous? D’abord, l’étonnante liberté de ces deux génies vis-à-vis de leurs partitions! Il est vrai aussi que le jeu de Ravel n’est pas d’une justesse infaillible… Mais si l’on dépasse l’aspect purement technique, on s’aperçoit de l’extrême finesse et de la personnalisation des touchers. Les dynamiques sont généralement faibles, les doigts semblent effleurer le clavier. Sans aucune brutalité. La clarté et la douceur sont stupéfiantes. D’autres exemples sont frappants comme ces deux volumes consacrés à des œuvres de Brahms interprétées par Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney ou bien les Études de Chopin par Pachmann et Paderewski…

La virtuosité des pianistes est stupéfiante, mais on est plus surpris encore par la fougue, l’engagement, parfois même les coquetteries, les ornementations intempestives que certains provoquent comme des tics. De toutes ces leçons de maîtres, on retient que les personnalités les plus fortes ne s’épanouissent qu’après une compréhension viscérale et profonde des œuvres. Schnabel dans les Valses de Josef Strauss et de Josef Lanner (qui oserait jouer cela aujourd’hui ?), Horowitz en 1926 dans quelques Préludes de Rachmaninov nous interpellent. D’où proviennent le charisme et le charme insensés de leurs lectures? Mystère.

Chaque année, Tacet publie trois ou quatre nouveaux CD des archives Welte-Mignon. À thésauriser.

S. F.

klassik.com –

--> original review

"The Steinway used by TACET makes the three composers seem like contemporaries - that's how present and delicate this sound is. It fully meets the highest standards. How wonderful it is the way the grand piabno learns to sing under Mahler's and Reinecke's touch. It is for this reason, above all, that it is worth hearing this recording, even if one already knows the recording of the three composers from other productions: the sound speaks for itself." (klassik.com)

Pizzicato –

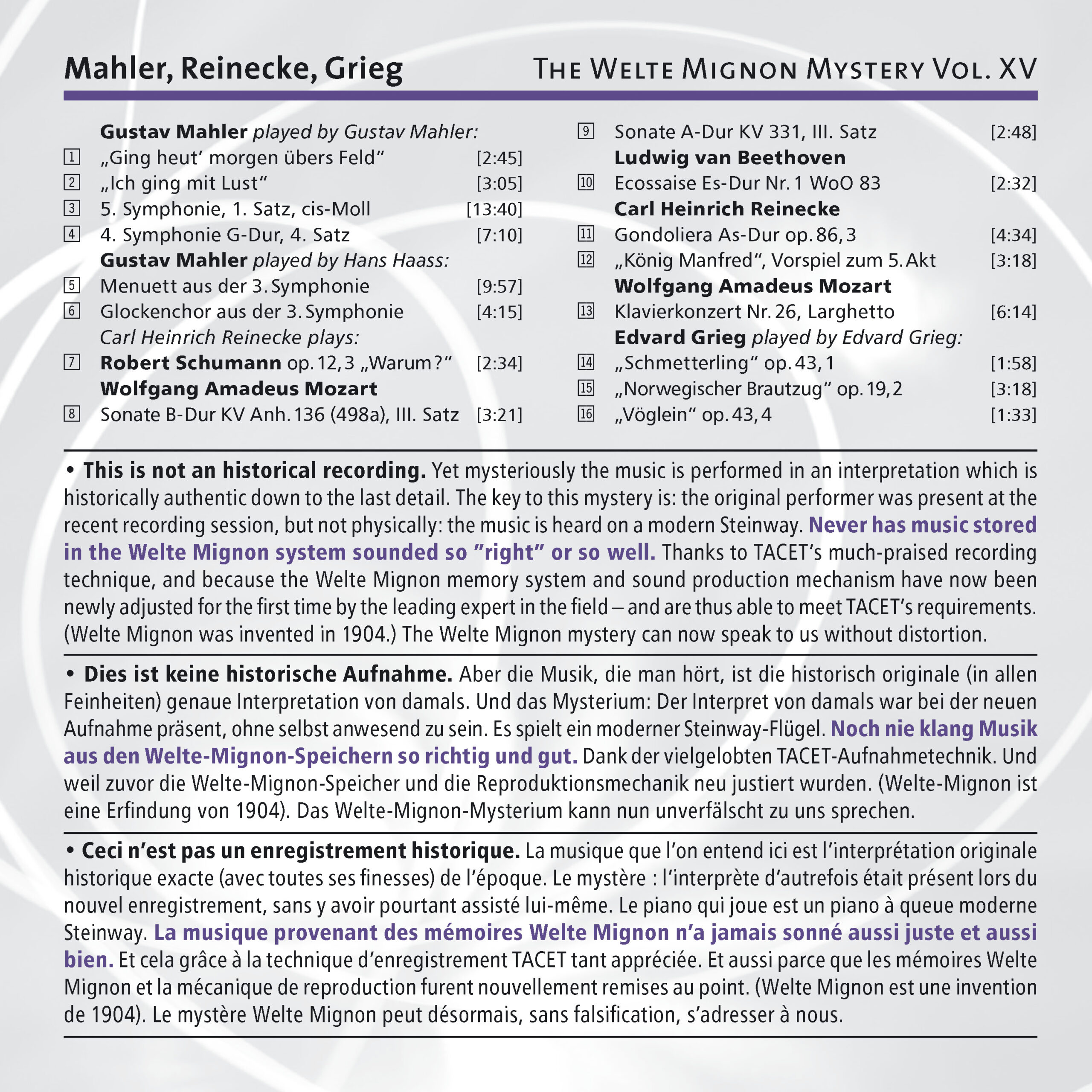

TACET continues its Welte-Mignon series with recordings of piano rolls made in the early 20th century by Gustav Mahler, Hans Haass, Carl Heinrich Reinecke, and Edvard Grieg. To clarify once more: what we hear is a modern Steinway grand piano being played by the Welte-Mignon mechanism using perforated rolls. Magnificent, modern piano sound with performers who have long since passed away! It goes without saying that the Mahler recordings are particularly fascinating—not just because we are currently in a Mahler anniversary year, but because his playing reveals much about the composer himself. The brisk tempo of Ging heut’ morgen übers Feld from Songs of a Wayfarer and the dramatic performance of the first movement of the Fifth Symphony are highly significant and present Mahler as an extremist—even at the piano. Equally noteworthy are the recordings of the 80-year-old Reinecke, while Grieg, in Butterfly, Norwegian Bridal Procession, and Little Bird, reveals interpretative paths into his compositions that many pianists today would hardly dare to take.

RéF

Audiophile Audition –

Mahler played several of his works at the keyboard in Leipzig on 9 November 1905, of which the extended piano transcription of his Fifth Symphony proves both febrile and fascinating.

I began this retrospective, Volume XV of "The Welte Mignon Mystery" series, with those inscriptions Edvard Grieg made 17 April 1906 and here reproduced on the modern Steinway in stereo - such a tonic after the scratchy, well-nigh acoustically impossible shellacs he cut that had appeared on Pearl. Grieg’s technique immediately strikes us with ist clean, resonant arpeggios and fluttering melodic line that mean "Butterfly." A detectable rubato informs this subtle playing. The Norwegian Bridal Song, a Scene from Folks-Life, charms with ist syncopations and upbeats, the trills and grace notes in witty taste. The dance becomes a stamping ground for fertile exercises in color and modal harmony. The “Little Bird” flits rather like a hummingbird, ist wings moving quickly. Angular and delicate, the lyric piece has nothing effeminate in ist nuanced phrases and often bold strokes.

Mahler played several of his works at the keyboard in Leipzig on 9 November 1905, of which the extended piano transcription of his Fifth Symphony proves both febrile and fascinating. More than the innate drama of the Trauermarsch score, with ist colossal "fate" motifs and indications of the fearful heart palpitations that would eventually claim his life, the ardent delicacy of the subsidiary motifs comes through, often in subdued and understated colors. Mahler’s uncompromising love of song and mountainous nature infiltrates this dark score as well as the last movement of the G Major Symphony--sans soprano solo‘s calling upon the Heavenly Life--that conjures up a gaudy, even barbaric feast in Heaven. Mahler rolls out the G Major arpeggios and fluttering runs in their uneven metrics, often capturing the contrapuntal tensions between individual lines until the series of descending cadences moves to a mystical resolution. Mahler’s upper registers prove somewhat insecure technically, but the plastic Elysium he invokes hath ist charms. The accents in the bass harmonies more than suggest Mahler’s sense of spatial dissolution for this otherworldly panorama.

Ignaz Friedman transcribed excerpts from the D Minor Symphony No. 3, and Hans Haass of the Welte Mignon studio performs the two selections in 1925. Haass negotiates the knotty music-box-like Menuett with technique to spare and a strong sense of the Mahler irony. The children’s choir rings with an innocence that haunts us with a hue of mortality. Ist major theme, of course, anticipates the last movement of the G Major Symphony. The opening song from "Songs of a Wayfarer" by Mahler himself frees the melody from ist accompaniment and indicates a tempo for any devotee of the First Symphony.

Carl Reinecke (1824-1910) contributed to the musical life at Leipzig, and even Schumann counted him among the "younger generation whom I find congenial." A solid pianist, Reinecke took a commission from Liszt to teach Liszt’s own daughters the keyboard. Reinecke was 80 years old when he sat down in 1904 for the Welte Mignon recording process, but his recollection of the Romantic ethos comes across in "Warum?" from Schumann’s Fantasy-Pieces, Op. 12, in which ritards and pulse fluctuations must be taken as part of the authentic style. An acknowledged Mozart scholar, Reinecke adds arpeggios, pedal, and rubato to those "gaps" in Mozart in which the performer must contribute his own invention. Mozart of the Menuet, K. 498a becomes more of a Romantic “salon” composer thereby. One hardly recognizes the first chords in the Rondo alla Turca, and Reinecke adds free melodic lines, but the contrast of textures proves engaging. The most beguiling Mozart arrives in the Larghetto from the Coronation Concerto, which flows with an airy grace undergirded by thick arpeggios in the manner of Mendelssohn. So, too, Beethoven’s E-flat Ecossaise remains an improvisation in stiff rhythmic periods rather a textual reproduction. The track listing for No. 11 says "Gondoliera" by Reinecke, but what we receive is Chopin’s Mazurka in B Minor, Op. 33, No.4, quite stylistic. The Act V Prelude to the opera King Manfred fuses strumming elements from Schumann and Wagner, along with an atavistic trill.

Gary Lemco