138 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery: Vladimir Horowitz

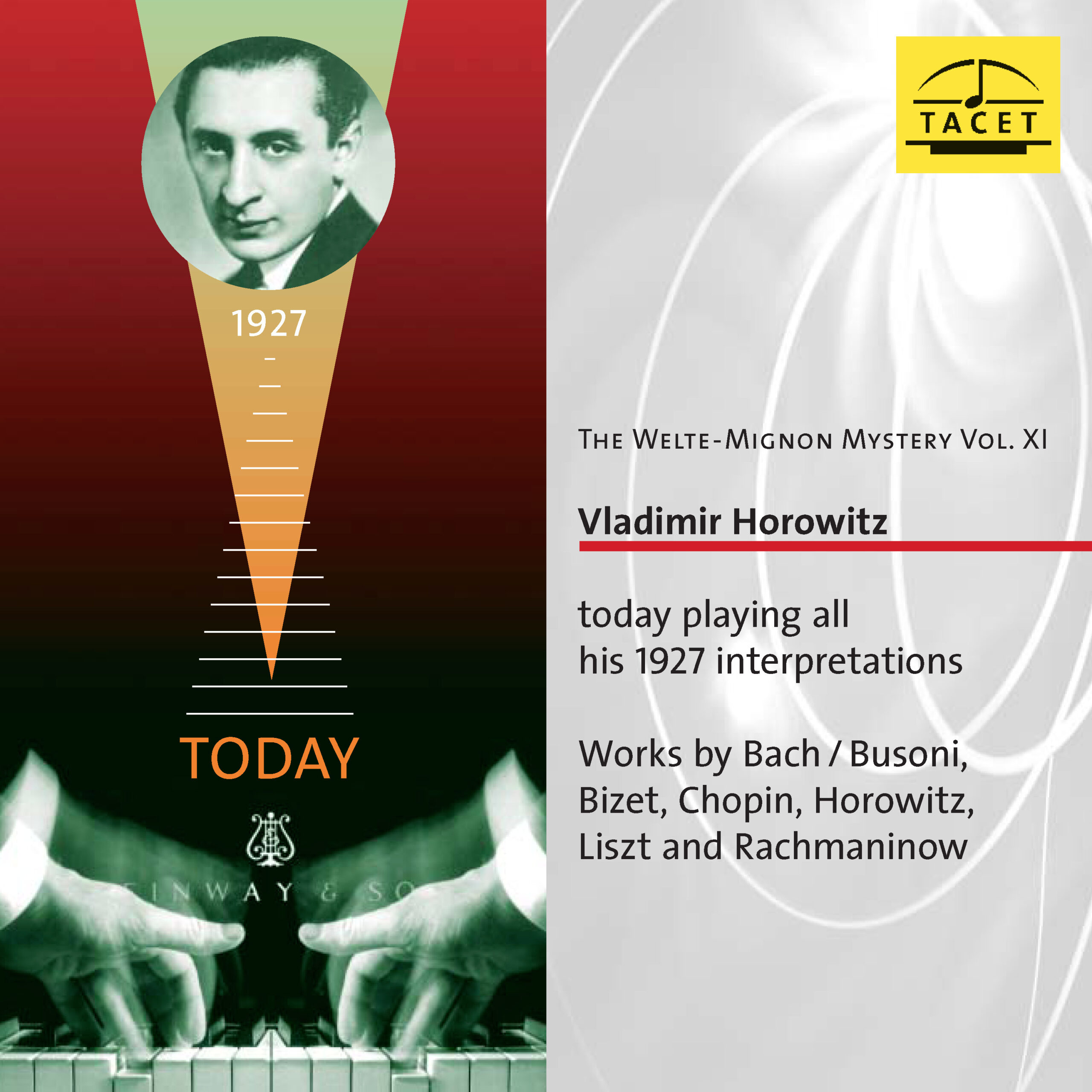

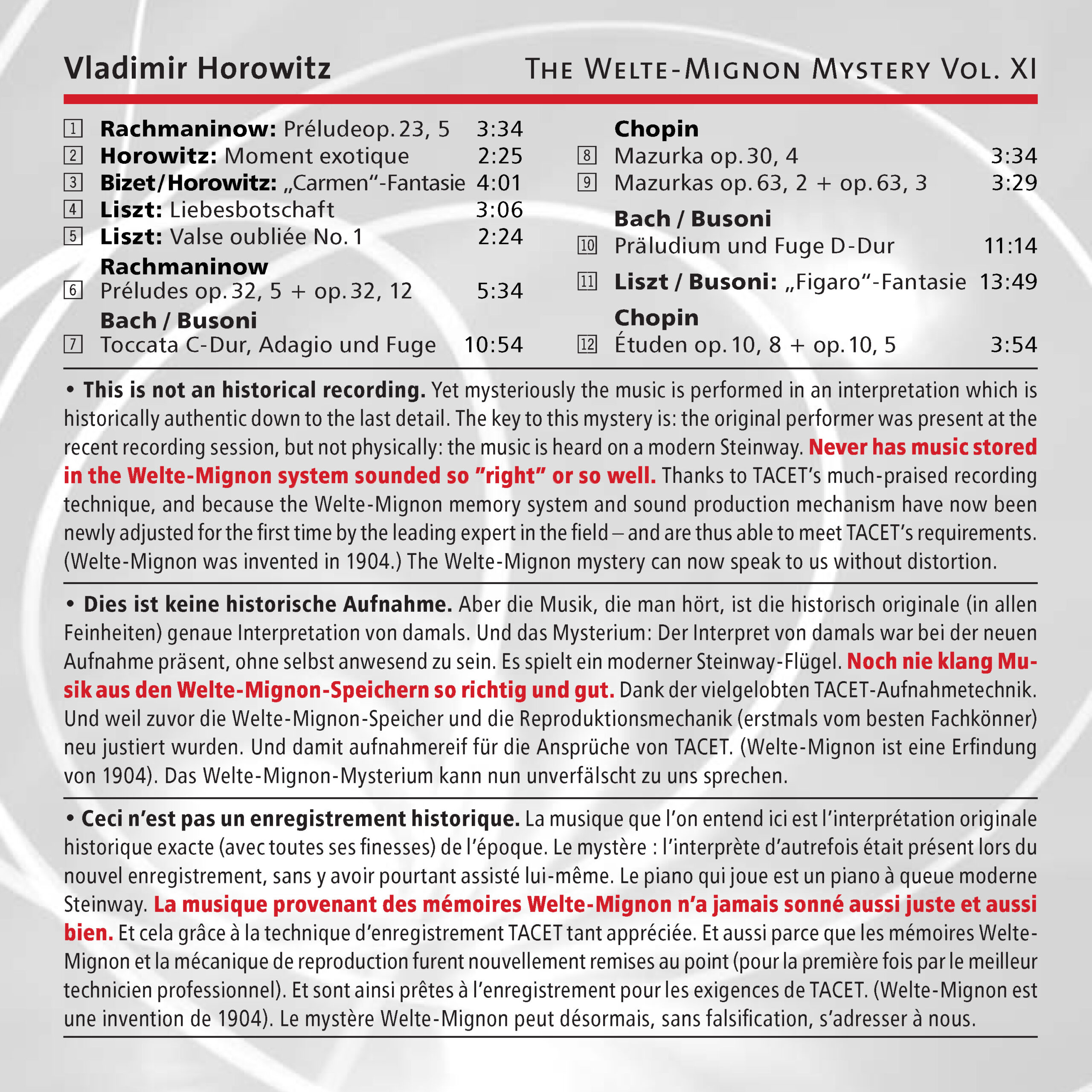

The Welte Mignon Mystery Vol. XI

Vladimir Horowitz

today playing all his 1926 interpretations.

Works by Bach/Busoni, Bizet, Chopin, Horowitz, Liszt and Rachmaninov

EAN/barcode: 4009850013808

Description

"(…) these are the earliest sound documents of Horowitz in existence. Horowitz's pianistic art is of the greatest freshness here: highly virtuosic and incredibly poetic at the same time - in short, genuine Horowitz!" (Pizzicato)

5 reviews for 138 CD / The Welte Mignon Mystery: Vladimir Horowitz

You must be logged in to post a review.

Pianiste –

THE LESSONS OF THE PAST

The Magic of the Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… spielen ihre Werke.

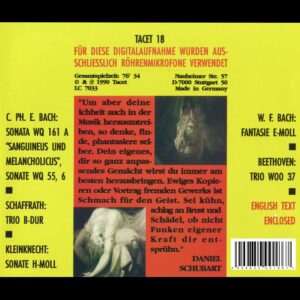

Would you like to hear Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, and Reger playing their own works on a modern piano? And how about a "perfect" restoration of the interpretations by the early Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne, and Schnabel? The German label Tacet offers an anthology of rolls recorded by the Welte-Mignon system. The system is simple, but the process of reproduction is particularly complex! In fact, the pieces played by the composers themselves were digitized from the device invented in 1904 by the company Welte & Sons of Freiburg. The perforated rolls of the time captured the touch, pedal play, and the finest nuances. Today, all that is needed is to transfer these recordings onto a concert piano.

It is therefore a real shock to hear, in optimal listening comfort, Debussy’s Children's Corner and some Préludes, as well as Ravel’s Sonatine and Valses nobles et sentimentales, all played by the composers themselves. What lessons can we take away from this? First, the astonishing freedom with which these two geniuses approach their scores! It is also true that Ravel’s playing is not always flawless… But if we look beyond the purely technical aspect, we notice the extreme finesse and personalization of their touches. The dynamics are generally soft, with the fingers seeming to merely caress the keyboard. No brutality whatsoever. The clarity and gentleness are astounding. Other examples are equally striking, such as the two volumes dedicated to Brahms’ works interpreted by Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney, or Chopin’s Etudes played by Pachmann and Paderewski…

The virtuosity of these pianists is staggering, but even more surprising is the passion, the commitment, and sometimes even the coquettishness, the occasional unnecessary ornamentations that some perform almost as if they were tics. From all these master lessons, we learn that the strongest personalities only flourish after a visceral and profound understanding of the works. Schnabel in the waltzes of Josef Strauss and Josef Lanner (who would dare play this today?), Horowitz in 1926 in some Rachmaninoff Preludes, speak to us. Where does the charisma and charm of their interpretations come from? A mystery.

Every year, Tacet releases three or four new CDs from the Welte-Mignon archives. Worth collecting.

S. F.

_________________________________________________

Original Review in French language

LES LEÇONS DU PASSÉ

La magie des Welte-Mignon

Debussy, Ravel, Mahler, Einecke, Grieg, Granados… jouent leurs œuvres.

Vous aimeriez entendre Ravel, Debussy, Strauss, Saint-Saëns, Reger jouant sur un piano d’aujourd’hui leurs propres Oeuvres? Et que diriez-vous aussi d’une restitution « parfaite » des interprétations des premiers Horowitz, Fischer, Lhévinne et autres Schnabel? Le label allemand Tacet propose une anthologie des rouleaux gravés par le procédé Welte-Mignon. Le système est simple, mais le procédé de restitution particulièrement complexe! En effet, les pièces jouées par les compositeurs eux-mêmes ont été numérisées à partir de l’appareil inventé en 1904 par la firme Welte & Fils de Fribourg. Les rouleaux perforés de l’époque ont capté le toucher, le jeu des pédales et les nuances les plus fines. Il suffit aujour¬d’hui de transférer ces témoignages sur un piano de concert.

C’est donc un véritable choc que d’entendre dans un confort d’écoute optimal les Children’s Corner et quelques Préludes par Debussy, mais aussi la Sonatine, les Valses nobles et sentimentales de Ravel sous les doigts des compositeurs. Quelles leçons en retirons-nous? D’abord, l’étonnante liberté de ces deux génies vis-à-vis de leurs partitions! Il est vrai aussi que le jeu de Ravel n’est pas d’une justesse infaillible… Mais si l’on dépasse l’aspect purement technique, on s’aperçoit de l’extrême finesse et de la personnalisation des touchers. Les dynamiques sont généralement faibles, les doigts semblent effleurer le clavier. Sans aucune brutalité. La clarté et la douceur sont stupéfiantes. D’autres exemples sont frappants comme ces deux volumes consacrés à des œuvres de Brahms interprétées par Nikisch, Lhévinne, Samaroff, Ney ou bien les Études de Chopin par Pachmann et Paderewski…

La virtuosité des pianistes est stupéfiante, mais on est plus surpris encore par la fougue, l’engagement, parfois même les coquetteries, les ornementations intempestives que certains provoquent comme des tics. De toutes ces leçons de maîtres, on retient que les personnalités les plus fortes ne s’épanouissent qu’après une compréhension viscérale et profonde des œuvres. Schnabel dans les Valses de Josef Strauss et de Josef Lanner (qui oserait jouer cela aujourd’hui ?), Horowitz en 1926 dans quelques Préludes de Rachmaninov nous interpellent. D’où proviennent le charisme et le charme insensés de leurs lectures? Mystère.

Chaque année, Tacet publie trois ou quatre nouveaux CD des archives Welte-Mignon. À thésauriser.

S. F.

Klassik heute –

It bears repeating: Tacet deserves high praise for elevating these historic roll recordings by legendary artists to contemporary sonic standards on a top-tier 'modern' concert grand. Under such luxurious acoustic conditions, these old—technically and production-wise problematic—performances gain a remarkably present, sympathetic dimension. This is especially true of the young Vladimir Horowitz in 1926, whose manual brilliance and technical reliability far exceeded the norms of his time. The piano heroes and poets of the early 20th century each had their unique charisma, but who among them could have delivered Busoni’s Figaro Fantasy—inherited from Liszt—with such athletic precision, untroubled by technical hurdles, yet still coaxing just the right seductive phrasing when needed? Horowitz, in this phase of operatic-pianistic exaltation, and in the daring flights of fancy of his Carmen Fantasy, must have left the musical world breathless. He had unlocked a new dimension of instrumental mastery.

Yet even Horowitz, in the infancy of sound recording, tailored his performances to the aesthetic expectations of his peers vying for public favor. A striking example is Rachmaninoff’s Prelude in G minor, Op. 23, No. 5—a piece whose bold rhythms and lavishly expressive middle section make it a touchstone of interpretive history. Compared to Sviatoslav Richter, Horowitz takes it at a gallop, a master of the vibrating moment, a sorcerer of instant magic. Thirty years later, Richter approaches it as an architect, meticulously constructing the composer’s blueprint. Where Horowitz accelerates through repeated chords and cascading octaves, Richter embeds them in a grander dramatic arc, steering inexorably toward the reprise—far beyond the sentimental songfulness of the central section. Even in their handling of thematic recall, the two diverge fundamentally: Horowitz snaps back to the original tempo with alacrity, while Richter creeps into it with deliberate care, ratcheting up tension until the prelude’s final, effervescent flourish—bestowing upon it a true sense of closure with utmost deliberation. Horowitz, by contrast, seems already mentally onto the next piece in this decorative finale, tossing off the phrase as an afterthought.

Few miniature works reveal as much as Rachmaninoff’s Prelude, Op. 23, No. 5 about how artistic sensibilities have shifted from one generation to the next. The most pianistically neglected version I recall—painful to admit—is by the otherwise revered Julian von Károlyi. Even in renditions by Ogdon, Lhévinne, or Rachmaninoff himself, I miss Richter’s admirable long-line perspective from first note to last.

All told, these resurrected Horowitz recordings are a balm, an adventurous journey with a willful guide through the scores: ‘Russian’-inflected Chopin mazurkas, audacious yet light-fingered Chopin études, a dash of his own genius (the Moment exotique), a somewhat careless—even dashed-off—Valse oubliée by Liszt, and two Busoni transcriptions of Bach’s organ works. Regarding the Prelude and Fugue in D major, BWV 532, I must note how much more structurally coherent and responsible György Cziffra’s BBC recording is!

A small correction for Tacet’s editorial team: Liszt’s Liebesbotschaft is an arrangement of Schubert—credit should be given where due in the track listing. And while we’re at it, those BWV numbers are rather well-known by now...

Peter Cossé

Stuttgarter Zeitung –

Anyone hearing these first recordings by the young Horowitz—captured in winter 1926 on a Welte-Mignon grand—will understand why the 23-year-old’s meteoric arrival left the piano world on both sides of the Atlantic in stunned awe. His technical perfection is staggering. In Liszt/Busoni’s fiendishly difficult Figaro Fantasy and his own Carmen Fantasy, Horowitz proves nothing was beyond his reach. Yet even more dazzling than these showpieces is the siren-like spell he weaves in Liszt’s Première Valse oubliée or Chopin’s Étude Op. 10, No. 5—where his fingers seem to glide with effortless brilliance across the black keys. What truly mesmerizes, however, isn’t just his death-defying tempos or sorcerer’s technique, but his kaleidoscopic tonal shading and musical command—qualities few of his peers possessed at such a young age.

Two exquisitely sung Busoni-Bach transcriptions, with their excessive rubato, foreshadow that Horowitz would later be hailed as the ‘last Romantic’ of the piano. Expressive poetry and manual magic unite in three Rachmaninoff preludes, while naivety and abyssal depth emerge in three Chopin mazurkas—agogically free, almost spoken in rhythm—pieces he revisited later, inviting comparison with his mature recordings. The real marvel of this anthology? We’re not listening to scratchy shellac transfers, but—thanks to Tacet’s cutting-edge remastering—recordings that sound as if they were laid down in a modern studio yesterday."

Uwe Schweikert

Pforzheimer Zeitung –

(…) Complementing this, TACET has released a sonically superb transfer of Horowitz’s piano-roll recordings, capturing him in the 1920s as a storm-the-heavens virtuoso in works by Rachmaninoff, Liszt, and Chopin.

tw

Pizzicato –

Vladimir Horowitz left behind a vast trove of historical recordings—and, well, they sound historical. But Horowitz also contributed to the roughly 4,500-title catalog of piano rolls recorded by Welte between 1904 and 1932. Now, TACET is releasing one of these early performances in fresh, modern sound—and we owe them gratitude, because these are the earliest surviving recordings of Horowitz in existence. Here, his pianism bursts with youthful vitality: blazingly virtuosic yet profoundly poetic—in short, the real Horowitz!