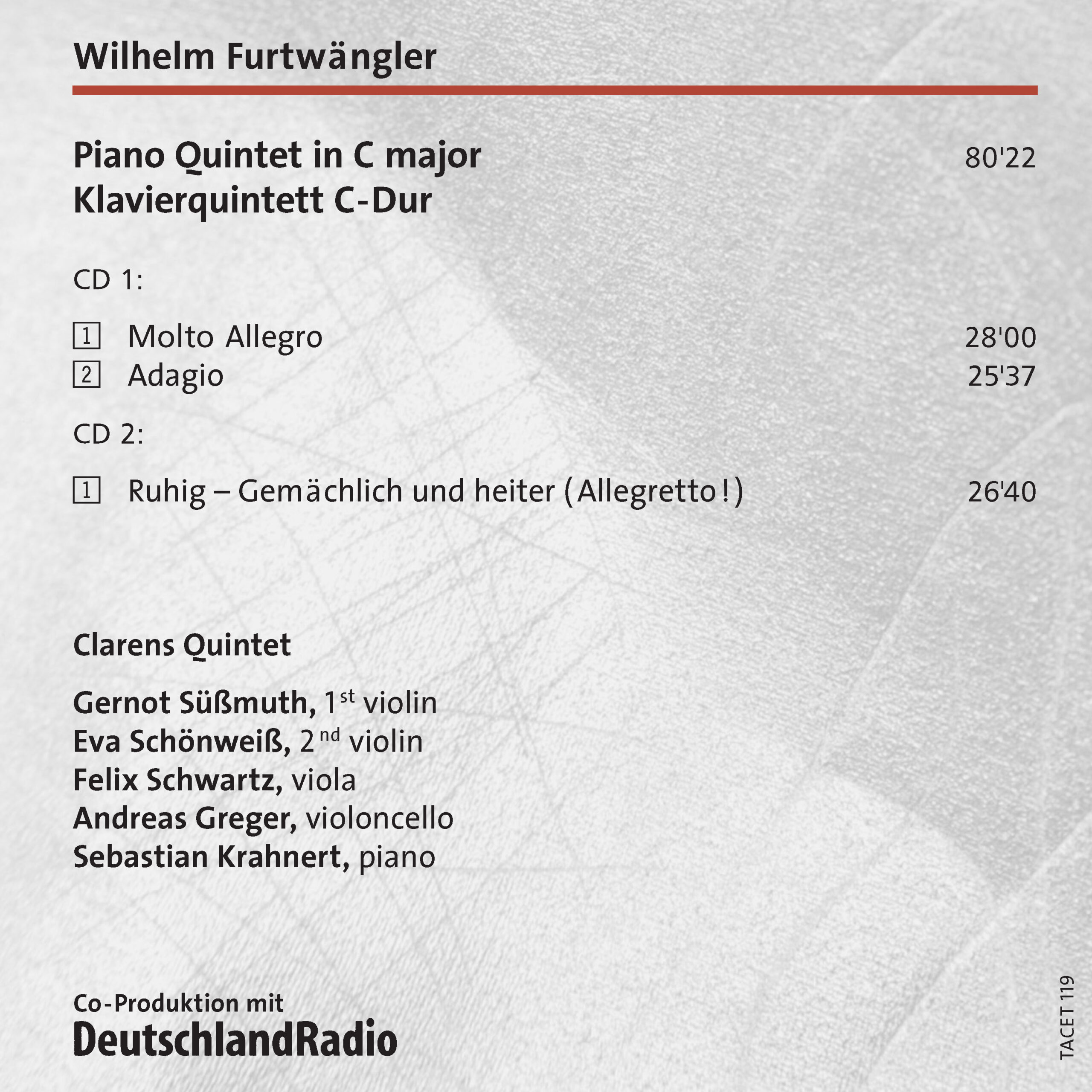

119 CD / Wilhelm Furtwängler: Piano Quintet in C major

Description

"What the legendary conductor always wanted more than anything was to be a composer. And what other works merely hint at is clearly obvious from this huge three-movement work, a child born of the pain of more than twenty years, a statement: Furtwängler was a man of longing who wanted to outdo Wagner and Bruckner in tonality and the span of feeling. The Clarens Quintet turns this document into an experience." (Kultur-Spiegel)

10 reviews for 119 CD / Wilhelm Furtwängler: Piano Quintet in C major

You must be logged in to post a review.

Pizzicato –

(...) The Clarens Quintet plays the movement very powerfully and intensely, and one listens with interest, but this first movement is still nothing compared to the following Adagio, in which the music attains a moving depth. The composer has headed the third movement with “Calmly leisurely and cheerful.” The Clarens Quintet, however, is by no means satisfied with that. Even here they approach the music in a very profound manner and, with all calm, also detect unrest in the music, which is played with tension and in which the mysterious side also continues to play a role. By no means a simple work, then, but music with which one can and indeed should engage. (...)

RèF

Classix –

“There will not be many people capable of mastering this music of catastrophe,” the teacher said to his pupil, referring to his Piano Quintet of 1934. “I am, after all, a tragedian,” replied the pupil—none other than the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler. He had worked on the quartet for two decades, never laying it aside as “finished.”

The Clarens Quintet has now dared to take it on, and the result is anything but tragic. With verve, heart, and intelligence, the musicians succeed in mastering the highly emotional and monumental work (lasting 80 minutes!) without it losing any of its intensity.

TPR

Stereoplay –

‘Very opposed to the fashion of the day,’” the great conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886–1954) described his compositional work, which, to his dismay, never received the recognition enjoyed by his interpretive performances of the old masters. The piano quintet, which grew over a huge span of time to gigantic dimensions, breaks the boundaries of chamber music drawn from Bach to Bruckner. Despite the seemingly harmless, but mostly artfully veiled, key of C major: in scope, dynamics, expressivity, and contrast sharpness, the work—more symphonic than intimate—would overwhelm sensitive contemporaries. The force of the opening movement can almost stun, the Adagio is an endless lament between shrill cries and the darkest melancholy. Only the third movement offers almost surprisingly cheerful, more accessible passages, though without any shallow charm.

The colossal quintet, created between 1912 and 1934/35, was not performed during Furtwängler’s lifetime. In the anniversary year, a third recording joins the two existing ones (Quatuor Elyséen and Danièle Bellik; Bayer; and Quatuor Sine Nomine and François Kerdoncuff; Timpani). This is by far the best: thanks to brilliant sound quality, but above all because it does not shy away from the extremes of the score, exploring tensions to the point of pain, conveying the tragic emotionality without restraint.

Thus, any discussions of Furtwängler’s epigonism or even his qualities as a composer become superfluous. The intensity of the highly precise performance admirably masks the conspicuous lengths. Triumph of the sound carrier, which Furtwängler always regarded with suspicion: it is hard to imagine that the pianist and the four strings could sustain this feat live.

Lothar Brandt

Klassik heute –

This first recording of Wilhelm Furtwängler’s symphonic piano quintet in C, which breaks all dimensions of conventional chamber music, was overdue; even connoisseurs knew it only by word of mouth until now. The Weimar activities and contributions to Furtwängler’s work—complete edition, recordings, performances, documentation—reach a special peak in this co-production of Deutschlandfunk with the label Tacet. The performing Clarens Quintet consists of section leaders from various symphony orchestras and the pianist Sebastian Krahnert, who is one of the initiators of the aforementioned activities; he also wrote the booklet text.

The piece, begun as early as 1912 and largely completed only in 1935, is a “giant snake” of three movements, each over 25 minutes long. There is much to discover in this cosmos—Mahlerian marches, outbursts of anger and dramatic scenes, Brucknerian chants, and even many passages of cheerful humor. One must certainly admire the courage Furtwängler showed in tackling such enormous structures, even though he probably knew that such spans required a foundation of thematic invention and contrapuntal treatment that he could rarely fully realize—perhaps most successfully in his Third Symphony and his Violin Sonata. This is precisely what makes this gigantic piece extremely elusive for the listener. Perhaps this is what Walter Riezler meant in his very tactful and diplomatic remark quoted in the booklet, “there will not be many people capable of mastering this music of catastrophe.” And perhaps Furtwängler knew it himself, when he replied to Riezler: “I am, after all, a tragedian.”

For getting to know this altogether fascinating music, this extremely commendable and committed performance is in any case well suited. Those who bring the necessary patience will be rewarded with many interesting impressions of Wilhelm Furtwängler’s music—even if it cannot compete with the structural and craft finesse, for example, of a Max Reger.

Benjamin G. Cohrs

Junge Freiheit –

(...) Such an exceptional work can probably only be mastered if the performers fully identify with it, perhaps even over-identify. Whoever wants the whole must go all the way. Gernot Süßmuth, Eva Schönweiß, Felix Schwartz, Andreas Greger, and Sebastian Krahnert exercise all the orchestral possibilities inherent in the interplay of the five solo instruments with sovereign command—even in the world-lost passages of the wonderfully softly and long-resonating middle movement, an Adagio, the work sounds like a symphonic poem, arranged for a chamber ensemble.

The highly expressive interplay of the five musicians sounds less like a dialogic exchange than like a fivefold monologue. Here Furtwängler speaks of his illusions, dreams, and presentiments. Here a Romantic, who always claimed the designation as an honorary title, does not seek to revive a thoroughly lived nineteenth-century Romanticism, but rather to open his listeners to the whole of life—for love, warmth, abundance, sensuality, and exuberance (...)

Jens Knorr

KulturSPIEGEL –

What the legendary conductor always wanted more than anything was to be a composer. And what other works merely hint at is clearly obvious from this huge three-movement work, a child born of the pain of more than twenty years, a statement: Furtwängler was a man of longing who wanted to outdo Wagner and Bruckner in tonality and the span of feeling. The Clarens Quintet turns this document into an experience.

Johannes Saltzwedel

Crescendo –

(...) Interpretation and recording are excellent.

PSa

Wochen-Kurier mit dem Heidelberger Anzeiger –

On November 30, the fiftieth anniversary of Furtwängler’s death will be observed, and on this occasion TACET already presents the CD version of the most monumental chamber work the composer ever created: performed by the Clarens Quintet, the C major Piano Quintet appears in a recording for which the usual term “interpretation” hardly seems appropriate. The members of the ensemble—Gernot Süßmuth and Eva Schönweiß (violin), Felix Schwartz (viola), Andreas Greger (cello), and Sebastian Krahnert (piano)—approach the one-and-a-half-hour giant work with such conviction, dedication, and enthusiasm that, for the first time, a window opens through which the true Wilhelm Furtwängler can be seen (...)

Ensemble –

The 5-Star Recording

It is almost a truism: once an artist has revealed his vocation for a particular musical field, he will not really be able to abandon or expand it. Only a few exceptions prove the rule. However, this usually has less to do with the artist himself than with the public, which has once formed an image of this artist and is hardly willing to re-evaluate it. This was also the case with the conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler, who as a composer never really gained solid footing. On the one hand, this was because his works hardly corresponded to the general taste of the time; on the other hand, because of the aforementioned insight. It is therefore not surprising that Furtwängler withheld many compositions from the public immediately.

Among them was the now-recorded C major Piano Quintet, which Furtwängler began as early as 1912. By 1915 he wanted to premiere it in Leipzig. But another 20 years were to pass—not only due to the composer’s self-critical attitude toward his work, but also because of numerous other obligations—before it was completed. “Of course I always see again that everything that wants to grow needs time, a lot of time,” Furtwängler said in 1920. But what kind of work ultimately emerged over these many years? A work that not only broke conventional limits by its sheer dimension, with a total playing time of over 80 minutes, but above all a chamber music work that testifies to Furtwängler’s complex compositional craft, emotionally charged depth, and expressivity.

The work presents itself insistently, almost backward-looking late Romantic. Yet this alone would contradict its statement. Rather, Furtwängler thought orchestrally even in all the intricate and almost fragile writing for these five instruments; moreover, every motive he develops and repeatedly processes conveys tragedy. Furtwängler himself described this work as “music of catastrophe.” And yet, from every phrase of these tragically full-blooded moments speaks a love of detail, a life-affirming phrasing that repeatedly manages to erase the tragic. The Clarens Quintet, composed of top-level chamber musicians, understands how to translate the density of thematic elaboration in a fascinating way, treating Furtwängler’s quintet as a great work of a unique expressive world, one to be explored, which in any case requires every second of intensity from the ensemble as a whole and from each individual due to its symphonic nature. A fascinating performance of an equally fascinating work.

Carsten Dürer

Der Musikmarkt –

(...) For the recording with the Clarens Quintet, the usual term “interpretation” hardly seems appropriate anymore. It is impressive with what conviction, dedication, and enthusiasm the members of the ensemble (...) tackle the one-and-a-half-hour giant work.

mz